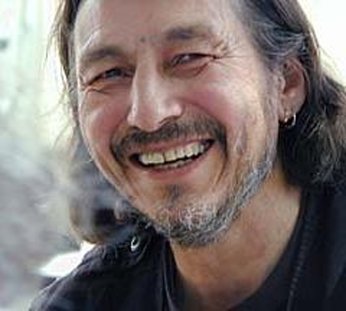

John Trudell Rising Above Violence, He Stood for Freedom

This article was in progress when its subject—poet, musician, actor and human rights activist John Trudell—passed away in late 2015. On February 15th this year, he would have celebrated his 72nd birthday.

We enjoyed many conversations extending back to 1986, when he was featured in the Church of Scientology Freedom Magazine. In my bookcase is a collection of his works and ideas, Lines From a Mined Mind, inscribed with a message that still touches me deeply: “Thank you for being my friend.”

John Trudell was a friend of humanity. At great personal cost, he stood against discrimination and injustice in all forms, and firmly for freedom and the inherent rights of all.

Bigotry and prejudice exhibit themselves in many ways, from derogatory remarks to increments of marginalization to denial of rights to acts of violence and—in the worst extreme—outright genocide.

“Our nation was born in genocide,” noted Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in his book Why We Can’t Wait.

By numerous estimates, tens of millions of native people died after the arrival of European explorers in the Americas. In American Philosophy: From Wounded Knee to the Present, authors Erin McKenna and Scott L. Pratt noted, “Indigenous people north and south were displaced, died of disease, and were killed by Europeans through slavery, rape and war. In 1491, about 145 million people lived in the western hemisphere. By 1691, the population of indigenous Americans had declined by 90-95 percent.”

“Our nation was born in genocide,” noted Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in his book Why We Can’t Wait, “when it embraced the doctrine that the original American, the Indian, was an inferior race.” Indeed, Native Americans were not recognized as “persons” under United States law until a May 12, 1879, judicial ruling and were not granted citizenship and the right to vote until 1924—although certain states barred them from voting until even later, with New Mexico the last to remove the barrier in 1962.

“When physical genocide slackened, cultural genocide—the enforced ending of Indian cultures, life styles, organizations, and values and thinking, of ‘Indianness’ itself—took over,” historian Alvin Josephy Jr. wrote in Red Power: The American Indians’ Fight for Freedom.

The federal policy of “termination,” formally pronounced by Congress in 1953, threatened to bring about the wholesale extinction of entire tribes. The policy aimed to end tribal sovereignty and break up tribal lands. By the mid-1960s, more than 100 tribes had been impacted, losing title to their lands and their right to govern as sovereign Indian nations.

As the 1960s crossed into the 1970s, Native Americans experienced an infant mortality rate more than double and an unemployment rate roughly 10 times the national average. The U.S. Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare reported in 1969 that “the average educational level for all Indians under federal supervision is five school years.”

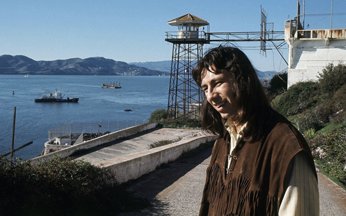

The Alcatraz Watershed

A pivotal event drew attention to these and related injustices. It began in November 1969, when a group calling themselves Indians of All Tribes landed on

Many Indian nations joined in peaceful protest of the policies that had endangered their traditional ways, their spiritual practices, and their very existence.

And, seemingly for the first time, America—and the rest of the world—listened. Over a period of 19 months, thousands of people of all races, including a long roster of celebrities and news media personalities, visited in support.

During that time, a young U.S. Navy veteran with Santee Dakota roots emerged as a leader and spokesman. In addition to articulating the protesters’ messages at press conferences, he directed broadcasts to the nation via Radio Free Alcatraz.

Possessing a sense of outrage toward discrimination and hypocrisy, counterbalanced by a sense of humor toward life itself, John Trudell gave voice to those who had long been oppressed, bringing the cause of Native American rights and tribal recognition to the center of the international stage.

A vital plank in the occupiers’ platform was establishment of a center on the island to observe and advance spiritual values and traditions. As described in a proclamation issued by Indians of All Tribes, “An American Indian Spiritual Center will be developed which will practice our ancient tribal religious ceremonies and medicine.”

While the protest continued at Alcatraz, Trudell occasionally left the island, playing a central role in events around the United States sparked by the occupation, including, in August 1970, at Mount Rushmore. There, protesters were rounded up and detained by park rangers after an unauthorized climb up the monument. As darkness fell, Trudell whispered to his friend and fellow leader Russell Means, “I’m going back up the mountain,” then slipped away from the guards, inspiring Means and others to follow to the top of

Not long thereafter, on Thanksgiving Day, at the landing site of the Pilgrims, Trudell hurdled the fence protecting Plymouth Rock and doused that icon with red paint—a symbolic protest of colonists’ forceful appropriation of Native American lands. The paint was removed but the worldwide impression was indelible.

Human Rights Abuses, No Longer Ignored

These and other demonstrations spotlighted long-ignored discriminatory practices and human rights abuses.

Attorney John Echohawk, founder and executive director of the Native American Rights Fund, told this writer that they “brought a tremendous amount of visibility and attention to the Native American cause.”

Echohawk, a member of the Pawnee Tribe, was working with Trudell to bring about the peaceful transfer of Alcatraz Island to Native Americans for multifaceted use as a university, spiritual and cultural center, and museum, when a federal force landed on June 11, 1971, and ended the occupation.

But the point had been made. After the need for change had become so obvious, centuries-old abuses could no longer be covered up or ignored. The

Alcatraz also ended the policy of termination, creating in its place a more enlightened one that allowed Native Americans to retain their identities and heritage. Between 1970 and 1971, Congress passed no less than 52 measures to bolster tribal rights to self-rule.

In 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court weighed in on tribal sovereignty, noting that “it provides a backdrop against which the applicable treaties and federal statutes must be read. It must always be remembered that the various Indian tribes were once independent and sovereign nations, and that their claim to sovereignty long predates that of our own Government.”

“Intelligent… Eloquent… Effective”

“John enhanced the dignity and order of the Indian cause,” said attorney Alexander “Sandy” MacNabb, a former Assistant Commissioner of Indian Affairs. He described Trudell to this writer as “one of the principal architects of making the issues clear so that the other side could understand.”

MacNabb, a Micmac, joined the American Indian Movement (AIM) in the early 1970s. He recalled being present at demonstrations led by Trudell, who chaired AIM from 1973 to 1979. “John always had a very cool head,” MacNabb said, “and he spoke in very clear language. From my experience with him, his statements were free of derision and hatred. He always talked in positive terms.”

“In protests and demonstrations,” said MacNabb, “the other side would frequently want to talk to John because he was a very rational, calm and kind person. He wasn’t ever trying to emotionally or intellectually kill the other side. He was never, ever, looking for praise for himself. He just wanted positive changes for Indians. And he was very successful at it.”

A consequence of his success in shaking up the status quo was accumulation of an FBI file in excess of 17,000 pages from 1969 to 1979. The bureau noted, “Trudell is an intelligent individual and eloquent speaker who has the ability to stimulate people into action. … Trudell has the ability to meet with a group of pacifists and in a short time have them yelling and screaming ‘right-on.’ In short, he is an extremely effective agitator.”

Trudell was aware that his activism on behalf of minority rights brought with it an element of personal danger. Indeed, he had been warned about retaliation for exercising his freedom of speech. But nothing prepared him for what happened in February 1979 after leading a demonstration in

That night, his home in Duck Lake, Nevada, was set afire. His pregnant wife, Tina, their three children, and Tina’s mother died in the blaze. The exact source of the tragedy remains a mystery.

Shattered by the loss, Trudell traveled the Western states and Canada, supported by close friends. A lesser soul might have withdrawn from life or, alternatively, sought vengeance. Trudell, however, was not one to quit and also realized how violence engenders more of the same. As he expressed it, “To win through violence, you have to be more violent and more aggressive than those you oppose. So how do you win? You become the new them.”

Embracing Peace

The killing of his family, Trudell said, “made me understand the violence in me,” which he described as a “live energy” so intense it made him realize he could never follow down that path. Instead, he embraced peace.

“In the course of that I started writing,” he said. “And then things started to fall into place. … I followed a decision I made to just not go to the violence, but to go on this other thing that makes more sense.”

His outlet for his thoughts and feelings were what he called “lines”—poetry—inspired by Tina.

Over the ensuing years, those lines, infused with humanity and insight, showed Trudell had come through his ordeal and expanded his scope to become a human rights advocate for people of all races, all ages—everyone.

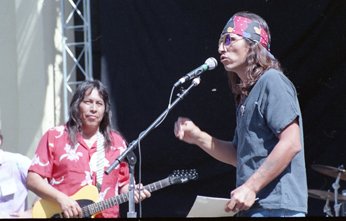

Teaming with gifted guitarist Jesse Ed Davis, his words were put to music on recordings that included the 1986 “aka Grafitti Man,” described by Bob Dylan as the best album of that year. With such bands as Grafitti Man and Bad Dog he performed in venues internationally, sharing the stage with many of the music world’s biggest names.

Trudell did “an excellent job of moving many people, myself included, with his poetry,” Bruce Johansen, professor of communications and Native American studies at the University of Nebraska, told this writer. Author or editor of dozens of books, Johansen called Trudell “a political critic of uncommon acuity” who “speaks to the essential issues that concern all of us, regardless of race, age or gender.”

Trudell’s themes included the need for peace, human rights and honesty in all relationships, the importance of the individual, and the connection between freedom and responsibility, as in this excerpt from his poem “Peace”:

Peace

Our relations all of life

Harmony in all living things

Peace

Proclamation not enough

Our responsibility emancipate earth

In a life lived with unique intensity and passion, John Trudell exemplified those words.