-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

The Triumph of the Irish-American People Over Religious Bigotry

America, in the early 19th century, was a fundamentally Protestant nation. Catholics were regarded with suspicion. Why? Well first of all, Catholics were “different”—they came from a foreign land, in this case, Ireland. Second, they pledged allegiance to an individual, a Pope in far-away Rome, a fact that appeared to be at odds with allegiance to America.

The word for this is “xenophobia,” a fear of strangers or foreigners and, by extension, anything that appears to us as strange or foreign—something we don’t see every day, something jarring and out of the ordinary, such as a hijab or skullcap or a mode of dress, a pigmentation of skin, the shape of an eye or an accent of voice that somehow disturbs our sense of what should be in our orderly world.

Xenophobia, then, is marked by irrational suspicion, fear and hate. It encompasses all prejudices against anything or anyone different from “the norm,” stretching back to the first time one person lifted a doubtful eyebrow at another.

And in the case of the Irish immigrants, that prejudice manifested itself as religious bigotry.

America first saw an influx of Irish immigrants fleeing famine and persecution at the hands of the British in the 1840s. Over a million people perished in the potato famine, otherwise known as The Great Hunger. Over 2 million more, nearly a quarter of the Irish nation, fled the island crammed in vessels nicknamed “coffin ships” for the shocking mortality rate claimed by the perilous Atlantic crossing.

Arriving at our shores, the Irish were met with hate and derision. Regarded as an inferior breed by many, and as a threat to American jobs and morals by others, the Irish found most doors closed to them. The stereotypical Irishman was a drunken, brawling, disease-carrying rapist, unfit for society.

The Irish brought with them customs and language alien to the residents here; but the main threat to many was their religion: Roman Catholicism.

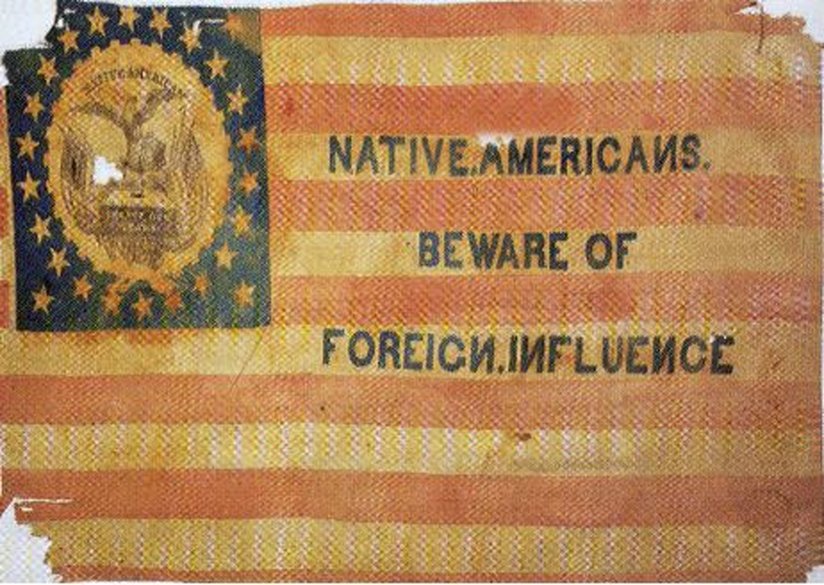

(Photo by Everett Historical/Shutterstock.com)

The fear and suspicion of the sudden influx of foreigners in general and Irish-Catholics in particular spawned a political movement known variously as the “Native American Party” or the “American Party,” but more broadly as the “Know-Nothing Party.” The Know-Nothings believed that the Roman Catholic Church was at the bottom of a conspiracy wherein the Pope and his “henchmen” were sending over their poorest, most unskilled people in order to overwhelm and subvert the American way of life.

The Know-Nothings (so called because of the supposed need for secrecy at their meetings and the answer always given when asked what had been discussed: “I know nothing”) succeeded in getting legislators and congressmen elected in several states, particularly Ohio, Massachusetts and Maryland. Attempts were made, some successful, to suspend the civil rights of Irish Catholics. (Help Wanted signs often included the warning: “Irish Need Not Apply.”)

If elections didn’t turn out the way the Know-Nothings wanted, the Catholics would be accused of stuffing the ballot boxes or otherwise rigging the elections. In 1855, riots broke out in Baltimore and Kentucky over bitterly fought elections, resulting in 22 deaths, while in Maine, several immigrant priests were tarred and feathered.

Though the Know-Nothings struck a chord with many seeking to scapegoat Catholics for their own failings, many were shocked and disgusted by the party’s rapid growth.

Abraham Lincoln expressed his concern in a letter written in 1855:

“I am not a Know-Nothing—that is certain. How could I be? How can any one who abhors the oppression of negroes, be in favor of degrading classes of white people? Our progress in degeneracy appears to me to be pretty rapid. As a nation, we began by declaring that ‘all men are created equal.’ We now practically read it ‘all men are created equal, except negroes.’ When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read ‘all men are created equals, except negroes and foreigners and Catholics.’ When it comes to that I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretense of loving liberty….”

What ultimately turned the tide for Irish-Americans and their descendants was, ironically for their haters, the ballot box. Turning out to vote by the hundreds of thousands, and then millions, they forced themselves into a prominent position on America’s stage, and instead of threatening the culture of America as feared, they absorbed it, contributed to it and strengthened it in every area imaginable: the arts, politics, sports, entertainment and science.

Then, in 1991, as a salute to the contributions of the Irish, an Act of Congress designated the month of March as Irish-American Heritage Month.

Recognized by proclamations from the White House, statements by the Marine Corps, videos by Irish performers and parades on Saint Patrick’s Day, the Irish experience in America has come a long way since the old “Irish Need Not Apply” days. The American experiment is still incomplete, still undergoing changes, some good, some not so good. The American people have changed as well, becoming more tolerant toward groups such as the Irish Catholics to the point where the nation that once regarded the Irish with fear and suspicion, now makes sure it’s wearing something green at least once a year.

So the Irish successfully crossed the invisible threshold from suspicion to acceptance in the eyes of a nation still sorting out its feelings.

What group will be next?