Unanswered Questions About Jonestown—Part Four: The Buried Agenda of Leo Ryan

On October 22, 1868, Congressman James Hinds was struck in the back by a shotgun blast while riding to a political event in Monroe County, Arkansas.

An advocate for the rights of former slaves, Hinds died at the site, but not before identifying the gunman, George Clark, a member of the Ku Klux Klan. As reported by multiple sources, Clark was neither arrested nor prosecuted for the murder. Hinds became the first U.S. congressman to be assassinated in office.

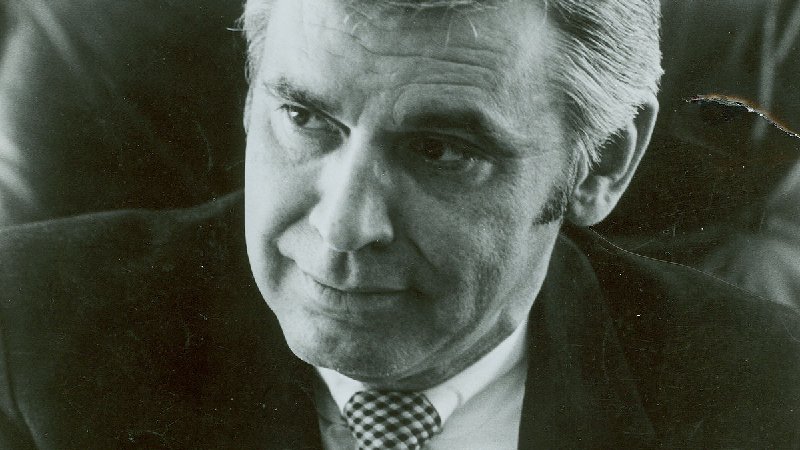

One hundred and ten years later, on November 18, 1978, Congressman Leo Ryan was hit by gunfire at the Port Kaituma, Guyana, airstrip.

To this day, the assailants that closed in on Ryan’s fallen body and riddled it with rifle and shotgun blasts have not been conclusively identified, although as many as a dozen or so “possibles” have been named in connection with the attack. And so, as in the case of Congressman Hinds, the killers of Congressman Ryan escaped accountability from any court of law.

Media coverage in the wake of the tragedy customarily featured Ryan in some prominent manner, often crediting his courage and leadership on vital issues of the day.

In a United Press International article on November 20, 1978, for example, Congressman Lester Wolff paid tribute to Ryan as exemplifying a “whole new breed of investigative congressmen … who go out to see things for themselves.”

Today, however, his name and, in particular, his interests can be hard to find in stories about the tragedy. An extensive November 2018 Time article posted on the net, for example, fails to mention Ryan; his name is relegated to a caption. And that caption shows not Ryan but the remains of some of those who died at Jonestown itself.

Who was Leo Ryan? The Time feature identifies him as “Congressman,” saying nothing about the man himself. Setting aside the Peoples Temple, what had occupied the attention of this “investigative congressman”? Such questions are rarely asked today.

His record can be found by anyone willing to look beyond superficial “retrospectives” about Jonestown.

A few short years before the tragedy, for example, he and Senator Harold Hughes of Iowa co-authored legislation that set limits on intelligence agency autonomy.

As described by former CIA officer John Stockwell in his 1978 book, In Search of Enemies, “The Hughes-Ryan Amendment to the National Assistance Act of 1974 required that no funds be expended by or on behalf of the CIA for operations abroad, other than activities designed to obtain necessary intelligence, unless two conditions are met: (a) the president must make a finding that such operation is important to the national security of the United States; and (b) the president must report in a timely fashion a description of such operation and its scope to congressional committees.”

Ryan’s zeal in working to bring about greater congressional oversight of clandestine operations led Brad Schreiber, author of the 2016 book Revolution’s End, to describe him as “the greatest legislative adversary the Agency ever had.”

Ryan’s chief aide, Joe Holsinger, recounted to me how Ryan had plunged into the role of watchdog, even dropping in unannounced at CIA headquarters to question officials on what they should have informed Congress, but hadn’t.

Holsinger knew his friend was treading on dangerous ground. “I told him to leave them alone,” he said, but that advice went unheeded.

“They were kept in solitary, harassed and annoyed until they would do anything asked of them to get them out; then they were given these drugs and would become like robots.”

A top item on Ryan’s agenda was to penetrate the secret world of psychiatric activities aimed at manipulating and controlling human behavior. He had been digging into potentially explosive matters regarding intelligence agency experiments and operations that employed drugs and other methods of coercive “mind control” conducted under such code names as MK ULTRA.

Of special interest to Ryan was the complex story behind the 1974 kidnapping of publishing heiress Patricia Hearst by the group that called itself the Symbionese Liberation Army.

On September 27, 1978, less than two months before the Guyana tragedy, Ryan wrote to then CIA Director Stansfield Turner. Noting that he had been conducting a “personal investigation of the Patricia Hearst case,” Ryan asked Turner to provide information “regarding CIA experiments using prisoners at the California medical facility at Vacaville.”

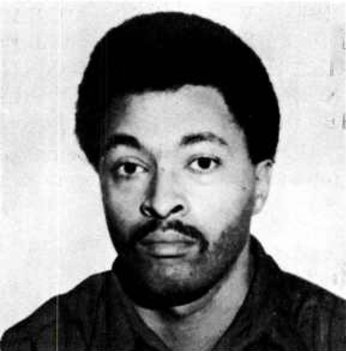

Ryan went on to inquire about “Donald DeFreeze, now deceased, who was the leader known as CINQUE of the Symbionese Liberation Army. The other person who may have knowledge of or who may have been referred to the CIA is Clifford Jefferson….”

An October 18, 1978, response came not from Admiral Turner but from Deputy Director Frank Carlucci. It read in part:

“Thank you for your letter of 27 September to Admiral Turner requesting confirmation or denial of the fact of CIA experiments using prisoners at the California medical facility at Vacaville.

“It is true that CIA-sponsored testing, using volunteer inmates, was conducted at that facility. The project was completed in 1968. …

“Your letter referred to Donald DeFreese, known as CINQUE, and Clifford Jefferson, both of whom were inmates at Vacaville. In so far as our records reflect the names of the participants, there is nothing to indicate that either was in any way involved in the project.”

Carlucci was less than forthright. Indeed, by improperly spelling DeFreeze’s name, he inserted a measure of plausible deniability. The CIA had not, as far as available records show, experimented on a man whose name was spelled “DeFreese.”

But there was more, as Ryan evidently suspected. One of those who dug into the many anomalies regarding DeFreeze and the Symbionese Liberation Army—a loose collection of a dozen or so people, hardly an army—was an experienced private investigator, Lake Headley.

In his 1993 book, Vegas P.I., citing letters from DeFreeze himself, Headley and co-author William Hoffman wrote, “According to DeFreeze, in 1970, at Vacaville, he was recruited by an alleged CIA operative Colston Westbrook to lead a behavior-modification experimental unit…. DeFreeze began operating as a double agent: (1) for Westbrook and the CIA, and (2) for the California Department of Corrections and the Bureau of Criminal Intelligence and Investigation.”

More recently, in Revolution’s End, Brad Schreiber wrote, “While we cannot know exactly all the drugs DeFreeze was subjected to at Vacaville, there is no doubt that he underwent coercive treatments.”

Much more was happening in the fall of 1978 preceding the Jonestown tragedy. In October, investigative journalist Jack Anderson devoted a widely syndicated column to the Vacaville experiments, quoting from an affidavit by the previously mentioned Clifford Jefferson: “In the early part of 1971, DeFreeze stated to me that the CIA was conducting tests to try out certain drugs on inmates, and he had been in on it…. These tests were on the third floor of the facility in B3. I went there and met two CIA men who were giving these tests. They gave me drugs, including mescaline, Quaalude and Artane. These drugs first made me terribly frightened, then other drugs were given to calm me down….

“DeFreeze stated that he had gone through the same tests and also knew of stress tests that were given to prisoners, in which they were kept in solitary, harassed and annoyed until they would do anything asked of them to get them out; then they were given these drugs and would become like robots.”

“The final result is not the whole story of the CIA’s attack on the mind. Only a few insiders could have written that, and they choose to remain silent.”

On October 26, 1978, John Marks wrote the Author’s Note that completed The Search for the “Manchurian Candidate,” his landmark summary of some 16,000 pages of documents obtained after a three-year Freedom of Information Act battle with the CIA regarding MK ULTRA and other mind-control programs.

For Leo Ryan, the MK ULTRA documents and the work of John Marks and other researchers would have provided keys to unlock areas of psychiatric experimentation and covert activities he had been seeking to explore.

And there was a need for further exploration. As Marks wrote, despite the release of the documents, “the final result is not the whole story of the CIA’s attack on the mind. Only a few insiders could have written that, and they choose to remain silent. I have done the best I can to make the book as accurate as possible, but I have been hampered by the refusal of most of the principal characters to be interviewed and by the CIA’s destruction in 1973 of many of the key documents.”

On page 56, Marks noted that Sidney Gottlieb, longtime head of the MK ULTRA program, “refused to be interviewed for this book.”

Twenty years later, in the late 1990s, psychiatrist Colin Ross, author of The CIA Doctors: Human Rights Violations by American Psychiatrists, telephoned Gottlieb at his Virginia home where the mind-control maestro had been enjoying an extended retirement with pastimes that included folk dancing and raising goats.

“I was astonished that he even picked up the phone,” Dr. Ross told me, noting that he clearly identified himself to Gottlieb as a psychiatrist who had written a book on MK ULTRA.

According to Ross, Gottlieb informed him that there had been “another unit besides his—a parallel unit” devoted to mind control. A unit that remains secret to this day.

Where was this unit located? “He seemed to be saying within TSD [Technical Services Division] at CIA,” Ross said in response to my question.

On October 16, 1978, two days before Carlucci’s letter to Ryan, John F. Blake, the CIA’s Deputy Director for Administration, wrote a memorandum that stated in part:

“The Agency is committed to identify, find and notify persons who may still suffer adverse effects from drugs that were administered to them without their knowledge as part of Agency sponsored drug testing programs. People who have been involved in searches pertaining to known projects (MKULTRA/MKSEARCH, BLUEBIRD/ARTICHOKE, and OFTEN/CHICKWIT) are confident that all records relating to those projects have been found. Nevertheless, a nagging uncertainty lingers in some quarters that there may yet be some unidentified project buried somewhere in the archives that no one knows anything about.”

The words of Sidney Gottlieb indicate that some truth lay behind the “nagging uncertainty” referred to by Deputy Director Blake. That in turn raises such questions as: If such a unit or project did exist, what was its mandate? How expansive were its activities? Why has its existence been kept secret? What individuals may have been involved? Would any of their activities be actionable under criminal or civil law? If so, how close was Leo Ryan to finding out?

In 2018, the introduction to this series noted that the Jonestown tragedy colored and tainted the manner in which many view religious organizations and religion itself.

November 18, 2019 will mark the 41st anniversary of that tragedy. While innumerable articles and books have been written about Jonestown, its final days remain a kaleidoscope of unresolved questions.

Fundamental to the confusion, as noted in this series, is the Big Lie that hundreds of people—including mothers with young children—lined up to willingly “drink the Kool-Aid.”

While that Big Lie has been challenged by some over the years, rarely have their voices been heard. By posing questions about the conventional narrative, STAND has cast light on the false scenario that has undermined and denigrated the subjects of religion and religious beliefs.

STAND continues to investigate events surrounding the matter, to provide a voice for those whose words have been squelched, and to push for an independent probe with sufficient resources to obtain honest answers to the many yet unresolved questions of Jonestown.

If you have information relevant to this posting, STAND wants to hear from you. Contact us at STANDLeague.org or send hard copy information to STAND, 1626 N. Wilcox Avenue # 715, Los Angeles, CA 90028. Identities will be protected on request.