-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

Another Victory for Inclusion—First Orthodox Jews in History Drafted by Major League Baseball

The old gag is that a Jew walks into a bookstore and asks for the title Great Jewish Baseball Heroes. The clerk hands him a book that’s two pages long.

As far as Major League Baseball goes, the apparency is there have been very few Jewish ballplayers. The truth, however, is that for many decades of the 20th century there were many more Jews in baseball than there appeared to be. For newly arrived immigrants from Eastern Europe, American sports was a ticket into inclusion and a possible career; but many Jewish athletes, fearing the repercussions of anti-Semitism, hid their religious and ethnic identities by the simple expedient of a name change.

“There must have been at least half a hundred Jews in the game but we’ll never know their real names,” Ford Frick wrote in 1925. “During the early days of this century the Jewish boys had tough sledding in the majors and many of them changed their name.”

For instance, the common Jewish name “Cohen” became “Cooney” or “Kane.” Reuben Cohen, taking no chances, changed his last name to Ewing. Michael Silverman became Jesse Baker. Henry Lipschitz morphed into Henry Bostick. Joe Rosenblum became Joe Bennett. James Herman Soloman became Jimmie Reese.

Many Jewish athletes, fearing the repercussions of anti-Semitism, hid their religious and ethnic identities by the simple expedient of a name change.

The paradigm began to shift, however, with the arrival of Hank Greenberg, a true superstar of the 1930s and 40s, and ultimate Hall of Famer. Unashamed and open about his Jewish identity, he was subjected to constant abuse and threats. At a game in 1947, he accidentally collided on the field with Jackie Robinson. Robinson who had just that season broken Major League Baseball’s color barrier, had, just days prior, received threats on his life and threats to kidnap his infant son. Cruelly, players on opposing teams pointed baseball bats at Robinson while making machine gun noises.

After their brief collision, Greenberg said, “Don’t pay any attention to these guys who are trying to make it hard for you. Stick in there. You’re doing fine. Keep your chin up.”

After the game, Robinson observed, “Class tells. It sticks out all over Mr. Greenberg.”

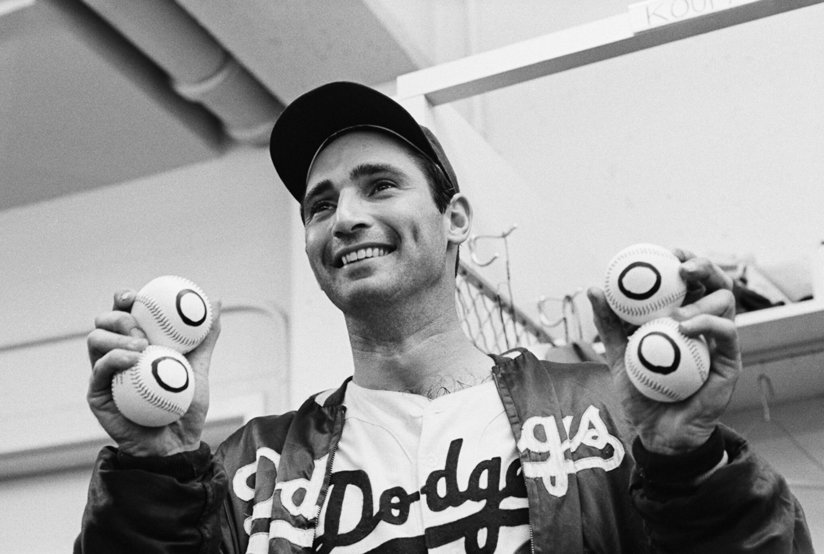

Hank Greenberg’s class made it easier for other Jewish ballplayers—including All-Stars Sandy Koufax, Alex Bregman, Ryan Braun, Al Rosen and Shawn Green, among many others—to play the game they loved without fear.

Koufax has been hailed as one of the greatest pitchers in the history of the sport.

In Greenberg’s day, and even in Koufax’s, a generation later, it was a matter of note and celebration when a recognized Jew made any sort of impact at the Major League level. But that has since changed. As baseball historian John Thorn wrote in 2014, “It is today routine, rather than remarkable, for Jews to be baseball players—stars and supernumeraries just like every nationality or creed. Is that a triumph? Yes, but it is also a challenge. What are those things that make Jews special—chosen, even—if not their outsider status? What will drive us to prove our people’s individual excellence, by ourselves or through our heroes? As a people forged in adversity, America’s Jews will have to find something else to supply the tie that binds. As in the past, baseball will be a help.”

Thorn’s observation was prescient. With last month’s draft selection of Orthodox Jews Jacob Steinmetz and Elie Kligman by the Arizona Diamondbacks and Washington Nationals respectively, history is being made. Major League Baseball has never had a player who was Orthodox, a branch of Judaism with which only 10% of American Jews identify. To be Orthodox means strict adherence to Kosher dietary laws and mandating absolutely no violations of the Sabbath: no riding in cars or even elevators and no switching appliances or lights on or off from Friday at sundown to Saturday at sundown, to name a few of the disciplines.

“As a people forged in adversity, America’s Jews will have to find something else to supply the tie that binds. As in the past, baseball will be a help.”

The Diamondbacks and Nationals have both shown a willingness to accommodate the teenagers’ religious needs, and instead of suspicion and hate, both players have reported nothing but support from Jews and non-Jews alike.

“At first, it was kind of just like, that’s who I am, who I’ve always been,” said Steinmetz, a right-handed pitcher from New York. “But once I did get taken, and I had all these people reaching out, and everyone’s… showing a lot of support and stuff like that. And I’m just getting random emails from people that I didn’t even know existed or from wherever in the world. And just knowing that most of the Orthodox Jews have my back and are supporting me, it was just, it was a great feeling.”

“I’ve pretty much had the same exact experience,” Kligman said. “Mostly people that are really just curious and wanting to learn about what we do on [the Sabbath] and what we do on holidays, what we can, what we can’t eat. I’ve had people that are super interested in here, they’ve come join us for Friday night dinner. But all of our experiences have been positive for me.”

Yes, some things do change for the better. We’ve come a long way from the days of the name-changing to avoid name-calling, and from the time of being singled out as a “Jewish ballplayer” to simply a “ballplayer.” Steinmetz summed it up perfectly when he commented, “You can stay committed to religion and also just be a normal baseball player.”

When all is said and done, and when the ink has dried and the contest is at an end, in the game of baseball, as well as in the game of life, the only question that really matters is, “Can you play the game?”