Beyond Labels & Exclusion: Multifaith Roundtable Explores Paths to Understanding

Who are you? What do you believe? Can we still work together, despite our differences?

These are questions often asked of faith leaders and clergy, and the last is generally answered with a smiling “of course!”

But the proof is in the doing. Can the history of conflict and even bloodshed amongst religions be reversed? Can the suspicions and bigotry which, in some cases, have persisted for centuries be set aside in favor of a unified push toward forming a better, more peaceful, more welcoming world?

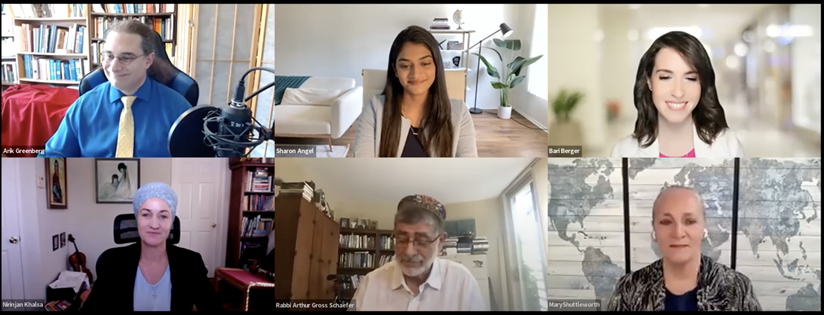

A constellation of diverse religious leaders, scholars, and activists convened in a virtual roundtable this past weekend sponsored by the Institute for Religious Tolerance, Peace and Justice to attack these thorny questions as well as lay the groundwork for mutual cooperation. Founder of the Institute, scholar, author and lecturer Dr. Arik Greenberg, set the tone and the theme of the forum at the outset: “The interfaith movement is at a crossroads,” he said, and it is time to go beyond “just breaking bread and sharing hugs. Now is the time to take the next step.” Dr. Greenberg challenged the keynote speakers and panelists to answer the question: how do we remain faithful to our own traditions while being tolerant of others?

“This room isn’t a room of just Jews, Christians, Muslims, Hindus. It’s a room of inclusivity.”

The first keynote speaker, author and theologian Dr. SimonMary Asese Aihiokhai, used the scriptures and parables of various faiths in his address to answer the question, “How can we reimagine identity issues that can be more inclusive?” Dr. Aihiokhai stressed that the instant we begin to use labels of identity for ourselves and God we are practicing exclusion. “This room isn’t a room of just Jews, Christians, Muslims, Hindus. It’s a room of inclusivity,” Dr. Aihiokhai said, “Some of us want to be the police officers of God, and that is wrong.” He explained that conflict is impossible among faiths when we all acknowledge a common God of diversity: “Our God is a God of differences, not exclusion.”

Responding and commenting on Dr. Aihiokhai’s remarks, was a panel composed of a diverse group in itself: national award-winning LGBTQ+ and social justice activist Mr. Justin Hager, J.D.; Assistant Professor of African American Thought and Practice in the Theological Studies Department of Loyola Marymount University, Dr. Kim R. Harris; Adjunct Professor and doctoral candidate at the University of Denver, Prof. Marji Karish; Born Again Christian from the Ventura County Interfaith Community, Mr. Keith Salvas; and human rights activist and Executive Director of Boat People SOS (BPSOS), Dr. Thang Nguyen Dinh.

Each panelist expressed his or her unique perspective and experience in their comments. Mr. Hager stressed that his presence at the forum was not as a person of faith, though he was raised in a family and community of faith who were shocked by his coming out. He said, “I think it is absolutely wonderful to have events like this… one of the things we don’t see enough of is these things within our faiths,” adding, “I don’t need to be right—just recognize me as a human being.”

Dr. Harris, who identifies as a Black Catholic, spoke from her own experience of being outside the “template” of what is thought of as the American Black religious experience. “People can’t imagine that we are Catholic or Jewish or Muslim or Buddhist. And some of that is from other African Americans, who can’t imagine that is what we are. So part of the engagement is being able to see within our own communities that there is an internal diversity that is there… there is a hospitality, an engagement that needs to happen.”

Conversing is inclusive, converting is exclusive.

Professor Karish shared her experience of being part of the largest interfaith event in Denver, the annual “langar-in-the-park.” Langar is a Sikh tradition wherein a free Indian meal is served and shared by a community regardless of who they are, thus unifying diverse race, religion, gender, sexual orientation, and class identities. Professor Karish said, “We served 10,000 meals every year across the community until the pandemic put everything on hold, and we will be starting up again in the fall.” She has set up a course at the University of Denver (DU) that will culminate in a “langer@ DU.” Professor Karish added, “I’m very grateful for being able to bring non-Western traditions focused on unity and community into a space where people may not have been familiar with the tradition in the past, but are now embracing the equity it represents.”

Mr. Salvas, in his turn, said: “When we talk about reimagining identity there is so much to do.” He shared a historic retrospective of diverse faiths coming together and working as a team. In the 1920s, Charles Evans Hughes, a Catholic, Ben Cardozo, a Jew, and social reformer Jane Addams toured, giving town hall talks about interfaith. The three became known as the “Tolerance Trio” and together brought about the formation of the National Conference of Christians and Jews (NCCJ), which is now known as the American Conference on Diversity. Our multifaith forums and seminars are an outgrowth of those early and effective efforts a century ago to foster cooperation and understanding among faiths.

Dr. Thang Nguyen Dinh, a refugee and escapee of communist Vietnam, brought his own unique story to the table. “Refugees face many barriers,” he said, citing language, housing, and economic hardships, “but they also have strengths.” Dr. Dinh outlined the paradoxical situation of the refugee community, a demographic composed of resilient individuals who are patriotic and appreciate their new freedoms, but who at the same time are often disconnected from their own religious and ethnic communities due to barriers of language, economics and social divides.

The other thorny question posed by Dr. Greenberg: “How do we engage in conversation that deals with hard and often divisive topics in a manner that is respectful, constructive, and promotes a deep understanding of each other’s worldview?” Tackled by the second keynote speaker, East African Muslim Interfaith teacher and preacher Sheikh Aziz Nathoo, said that his toolkit consists of two words: respectful dialogue. Visiting the same well as the first keynote speaker, Dr. Aihiokhai, Sheikh Nathoo also used scripture and parables to support his points. Taking a cue from the Holy Quran, he said, “We are instructed to compete with each other, but compete in good deeds.” He encouraged all to attend the festivals and ceremonies of other faiths—“breaking bread leads to breaking dread”—to make friends and to “ensure you are conversing rather than converting. Conversing is inclusive, converting is exclusive.” Sheik Nathoo urged us to unite with others and create a tsunami of religious tolerance. He concluded: “Every one of us is an ambassador and all our actions have a resounding effect,” before quoting the 13th-century Persian poet, Rumi: “You are not a drop in the ocean. You are the entire ocean contained in a single drop.”

“How do we see each other? Through the lens of curiosity, of wonder, or of exclusion?”

On the second panel, responding to Sheikh Nathoo’s insights, were President of United for Human Rights International, Dr. Mary Shuttleworth; Senior Instructor of Theological Studies and Clinical Professor of Jain and Sikh Studies at Loyola Marymount University (LMU), Dr. Nirinjan Khalsa-Baker; Professor of Business Law, Ethics, and Sustainability at LMU, Rabbi Arthur Gross-Schaefer; Director of STAND League, Scientologists Taking Action Against Discrimination, Ms. Bari Berger; and roundtable moderator, author, TV show host, entrepreneur, humanitarian and motivational speaker, Ms. Sharon Angel.

Once again, the panelists drew on their own backgrounds and experiences in responding to Sheik Nathoo. Dr. Shuttleworth cited her upbringing in apartheid South Africa and related how, in searching for respect and common ground, she discovered the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights—specifically Article 18 on freedom of thought and religion. Dr. Shuttleworth also emphasized Article 29, wherein everyone has a responsibility to their community to see that others are aware of these rights as well. “So to me as an educator, it is important to teach our children what are the common grounds. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is a good solid stepping stone.”

Dr. Khalsa-Baker touched on the Sikh concept that we are all one, and part of the Divine Light. “How do we see each other?” she asked. “Through the lens of curiosity, of wonder, or of exclusion?” Dr. Khalsa-Baker said that we need to transcend our own emotions so that we can listen with respect and humility to open up a space of grace. “What does it take?” she added. “A lot of courage, support, and resources from others.”

Rabbi Arthur Gross-Schaefer commented, “We are not the chosen—we all are. Who is my enemy? An enemy is someone whose story I have not heard.” Like Sheik Nathoo, he quoted the poet Rumi: “Out beyond ideas of rightdoing or wrongdoing, there is a field. I will meet you there,” to illustrate that despite our differences—or possibly because of them—we of different beliefs must find common ground. Rabbi Gross-Schaefer added that a lot of people don’t hear God speak to them, “A lot of people walk past the burning bush. In the spiritual tradition, you have to search for God and then God will speak to you. But it also comes from listening to others.”

“Time to start doing the hard work.”

Ms. Berger pointed out that much of what brings different faiths together is the similar problems they face. She said, “We should be investing our energies in discovering the things we passionately agree about, and figuring out how we can use that agreement to better the world. And one thing I believe I can safely say we all agree on is that our religious freedom is important to us and we want the right to practice our faith freely and with dignity.”

Roundtable moderator and panelist, Ms. Sharon Angel commented, “When we come from generations of a particular religion it is sometimes hard to understand other faiths.” She spoke of the necessity of a healthy bit of “holy envy” in order to respect the other person, their beliefs, and to live a better life sustaining our own beliefs. Ms. Angel also spoke about the power and importance of story-telling to deconstruct what otherwise may be a difficult and complex subject. When you are drawn closer to God, “you are drawn closer to unity, justice, and peace for yourself and for others,” she said.

If the roundtable participants represent a sample size of the larger tapestry of diversity among religions, the desire to get along, understand, and cooperate is more than present.

What comes next, is, in Dr. Greenberg’s words, “Time to start doing the hard work.”