-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

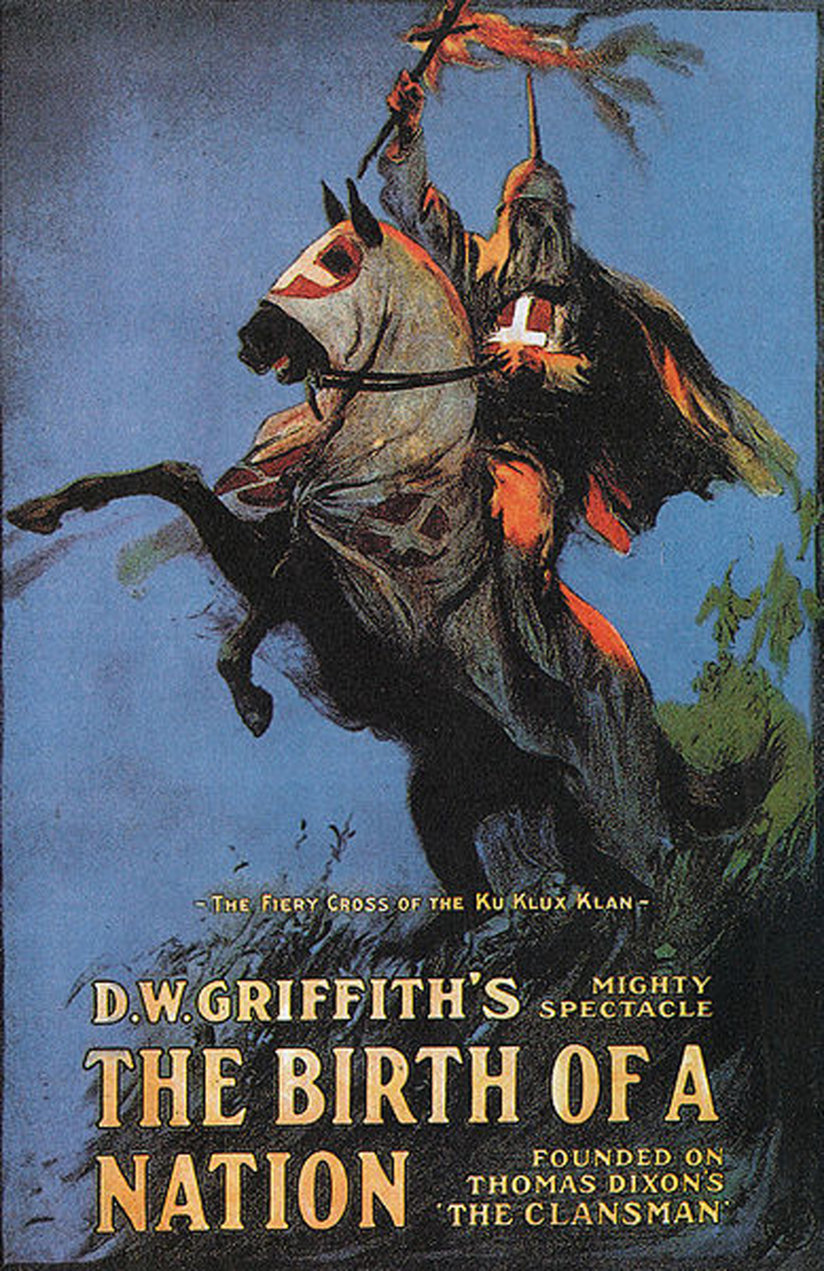

Black History Month Marks the Anniversary of “The Birth of a Nation”: Hatred Written With Lightning

It was hailed as “the world’s mightiest spectacle,” “the eighth wonder of the world,” and “history written with lightning.” It was the biggest, longest, loftiest, and most profitable movie in history until Gone with the Wind a generation later. It was D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, unleashed upon the world 106 years ago this February, Black History Month.

With a score performed by the Los Angeles Philharmonic at its L.A. premiere (the first time ever that a symphony orchestra accompanied a motion picture) and favored by a private screening at the White House (another first) followed by a special viewing by members of Congress, the Cabinet and Supreme Court—whose members interrupted it with frequent bursts of cheers and applause—The Birth of a Nation was big in every way.

Its 190 minutes depicted a twisted, white supremacist version of the Civil War and Reconstruction, based on the book and play The Clansman by Thomas Dixon Jr., vilifying African Americans and revering the Ku Klux Klan. The film, released during the 50th anniversary year of the end of the Civil War, opened old wounds and revived old hatreds. Riots and protests broke out in many cities where the film was shown, most notably in Boston and Philadelphia, and for a time the film was banned in Chicago, Denver, Kansas City, Minneapolis, Pittsburgh and St. Louis.

The NAACP sent letters and telegrams of protest to the Motion Picture Commission denouncing the film and its message, stating in one letter: “The Birth of a Nation is a glorification and exaltation of the Ku Klux Klan, an organization avowedly for the purpose of creating racial and religious prejudice against various elements of American citizens.”

The film opened old wounds and revived old hatreds.

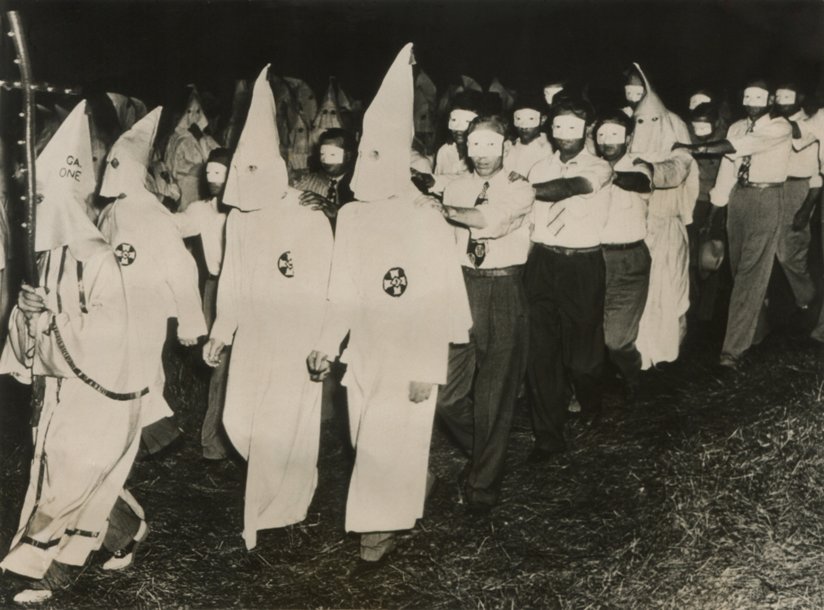

The Ku Klux Klan, a paramilitary domestic terrorist organization founded by ex-Confederate soldiers in late 1865, had rampaged unchecked throughout the South for six years spreading murder and destruction in African-American communities until an Act of Congress allowed President Ulysses S. Grant to impose martial law on the counties where the Klan flourished, effectively ending it.

For over 40 years there had been no KKK, but the NAACP recognized that the embers of its malice were still aglow, requiring only a spark to rekindle the flame. The Birth of a Nation provided that spark, for later in the same year it premiered, the long-dead Ku Klux Klan was reborn in Stone Mountain, Georgia, and quickly grew during the 1920s in both the North and South, expanding its umbrella of hatred to encompass not only Blacks, but Jews and Catholics, and all “non-Aryans” as well.

The impulse to propagandize and stoke hatred was quite conscious in the movie, which included such subtitles as “All whites must salute negro officers on the street,” “On Election Day all blacks are given the ballot while leading whites are disenfranchised,” and, captioning a scene depicting former Union soldiers sheltering a once prominent Southern family fleeing black marauders and their white allies, “The former enemies of North and South are united again in common defense of their Aryan birthright.”

Actors in full KKK robes, gold-trimmed, stylized and made glamorous by Griffith’s art directors, greeted patrons at the film’s premiere in Los Angeles.

At a court hearing in New York involving the NAACP’s formal complaints about the film, representatives of the motion picture, including Griffith himself, his attorney and Clansman author Thomas Dixon Jr., stoutly defended the film, largely on the basis of its phenomenal success (“one in every 18 persons of the total population of the United States has viewed this picture”), its critical raves, and the fact of its being shown to the president and dignitaries at the White House. All reports of violent actions and riots were dismissed as trumped-up, political, and in one case, “an effort to manufacture a negro demonstration and create a disturbance.”

Actors in full KKK robes, gold-trimmed, stylized and made glamorous by Griffith’s art directors, greeted patrons at the film’s premiere in Los Angeles.

The judge in the hearing found, “as an incitement to crime, the picture has delivered well-conceived, admirably executed propaganda to inflame the whole gamut of passions of whites against the negroes… [T]he exhibition of such a photoplay definitely calculated to arouse racial hatred is most dangerous and is likely to be the means of precipitating violence, riot, and property destruction.”

The judge ruled that the permit for screening be revoked from the film’s production company, but that ruling notwithstanding, the film continued to be screened, and enjoyed profitable revivals throughout the ’30s and ’40s.

The film’s director, D.W. Griffith, himself the son of a Confederate colonel, was surprised at the controversy his film had aroused. Neither he nor author Thomas Dixon Jr. could understand how anyone watching the movie could conclude that there was any prejudice meant or implied in it. They felt, rather, that they were enlightening both blacks and whites in certain hard but necessary truths.

In a filmed 1930 interview Griffith called it simply “a great story.”

“It’s about people who were fighting against great odds, a great struggle,” Griffith reflects, puffing on a cigarette, sitting in an easy chair in front of a fire, a Confederate saber prominent on a table to the side. “A great story.”

Griffith reminisced about cherished childhood memories of his—of watching his mother “as she stayed up night after night sewing robes for the Klan. The Klan was needed back then.”

Griffith’s racism extended so far as to exclude African-Americans from playing black characters who came in contact with white actresses in the film. These were portrayed by white actors in blackface, as were most of the black characters.

Griffith’s position in the Hollywood pantheon of immortals is undisputed. Not one single motion picture produced in the past 106 years is not, in some way, in his debt; Griffith was the first to introduce the close-up, the tracking shot, the pan, the dissolve, and many other film techniques that make film what it is. He was the first to shoot realistic battle scenes, cleverly deploying hundreds of extras to create the illusion of thousands, the first to “cut away” from one scene to show something else happening at the same time. He has justifiably been called “The Father of the Motion Picture.”

But Griffith used his genius to amplify the lie of white supremacy, an abomination that casts a shadow across the world and was at the core of the bloodiest century in human history. This, to his everlasting shame, was Griffith’s legacy, and it is, as we observe this Black History Month, how we remember him.