-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

Did the Supreme Court Just Strengthen or Weaken Religious Freedom?

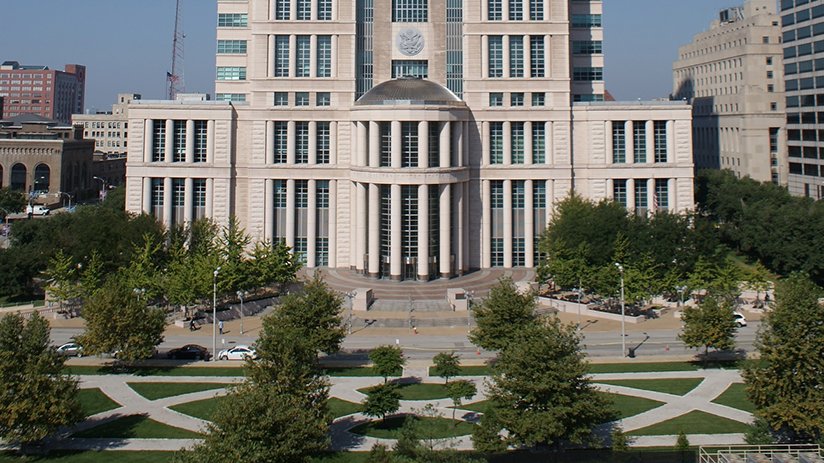

Many generations of Supreme Court Justices have tried to define the correct balance of church and state.

On June 26, a new chapter was written in that history when the Supreme Court ruled that it was unconstitutional for the State of Missouri to deny funding to a Lutheran Church-run preschool to resurface its playground to make it safer for children. Since the church met the religiously neutral criteria for the grant it submitted in 2012 better than most of the other applicants, and because the playground was not itself a religious space or activity, the Supreme Court concluded that the Missouri government had no right to deny the preschool funding solely because it was run by a church.

In no time, the decision had been dissected by legal scholars, advocates on all sides of church-state issues and journalists specializing in legal affairs.

Those who praised it feel it protects churches from discrimination. The dissenting Justices and their supporters, on the other hand, are concerned that it will weaken the separation of church and state and lead to government subsidies for religion. Still others (including two Justices) supported the overall decision but felt that it didn’t go far enough, as they had hoped for a broader ruling that would enable state funding of religious charter schools.

The field of education has long provided a testing ground for how the United States applies the basic principle that religion and government should be kept separate.

The Plymouth Rock Pilgrims of four hundred years ago who fled to the American wilderness because they faced the death penalty or long, brutal imprisonment for leaving the Church of England would probably wonder what all the fuss was about, and I’d forgive them for it. But in truth, the discussion is not about the playground, the roughly $20,000 it is going to cost to replace gravel with more kid-friendly material, or “a few extra scraped knees” (to borrow the words of Chief Justice Roberts). In fact, the new governor of Missouri had already reversed the previous administration and decided to make the funds available to the school before the Supreme Court’s decision.

But the case attracted attention because advocates of religious charter schools were hoping for a broad enough ruling to require states to fund them and their opponents wanted the Court to put an end to the possibility. What both sides got was neither: the court issued a narrow ruling on a specific issue but the subject will certainly come before the court again.

The field of education has long provided a testing ground for how the United States applies the basic principle that religion and government should be kept separate. The battle over prayer in schools is only one example of the many controversies that have arisen over the years in that sphere. But it wasn’t always this way.

When public education became widespread in the early nineteenth century, a largely Protestant nation for the most part saw no problem with including the Protestant Bible and Protestant theology as part of the curriculum in many public schools. Problems arose when children of the many waves of non-Protestant immigrants began entering school systems. For example in Boston in 1859, a Catholic child was severely beaten by his teacher for refusing to recite the Protestant version of the Ten Commandments. When his parents sought a legal remedy, in spite of the First Amendment and a very similar provision in the Massachusetts State Constitution, the courts found in favor of the teacher.

The Catholic Church response to discrimination was to found its own network of parochial schools which generated a widespread reaction, the most severe of which was an Oregon law that effectively banned parochial schools by requiring children to attend public school. It was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in the 1920s.

Since then, there has been a growing body of laws and court decisions about what support governments can and cannot provide parochial schools of various religions. The debate over support for religious charter schools is only the latest manifestation of a basically unresolved conflict.

Over the years, many people have written and spoken very eloquently in favor of different and often contrary ideas on religion and public education as well as worked diligently to put their ideas into practice. There is no one-size-fits-all solution that will completely satisfy the conflicting and disparate demands of our very heterogeneous society.

For that reason, I’d like to make a plea for us to recognize that there is a purpose in all of this: to help a future generation thrive in the world they will inherit and make.

Whether they will be able to do so depends on the education they receive now. I believe most people want a society composed of well-educated, skilled, ethical citizens who can evaluate information and decide for themselves what is right and what is wrong, what to believe or not to believe, be it religious or secular. A spirit of tolerance and a willingness to see things from other viewpoints could do a lot to bring that ideal closer to reality.