-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

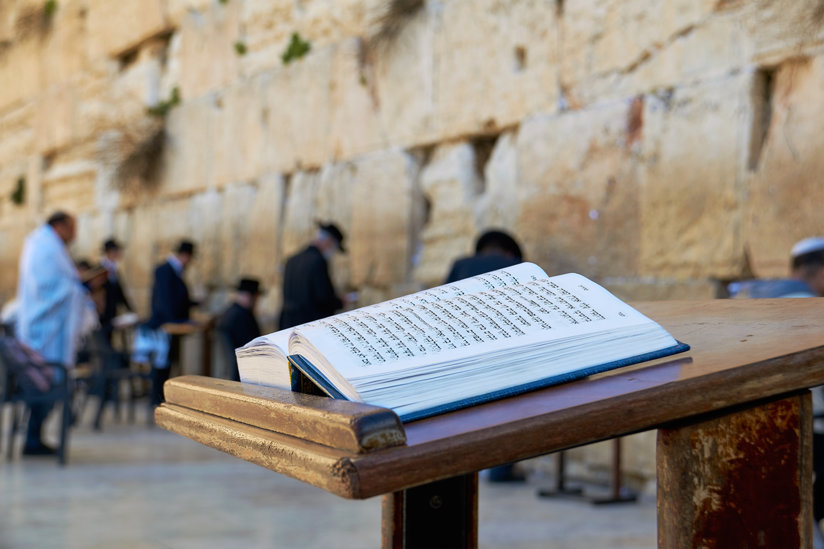

Hanukkah: A Holiday For All Who Believe Freedom of Religion Is Worth Fighting For

Hanukkah, though the most minor of Jewish festivals, is the most contemporary to our own time both in proximity, 163 BCE, and in relevance.

The two great external enemies of faith are coercion and comfort. The Hanukkah story represents a unique moment in history when a people and its religion were challenged by both. Both can undermine—and ultimately exterminate—a people. Coercion does it with tyrannical decrees and threats of punishment. Comfort does it with the invitation to relax into assimilation and apostasy.

In the late 170s BCE, the Seleucid Greeks ruled Judea (modern-day Israel) and times were comparatively good for the inhabitants. The law protected Judaism, and Jewish culture was treated with respect. In this comfortable climate, however, many Jews found it easier and more fashionable to adapt themselves to the “modern” Greeks. They abandoned their religion and customs, no longer practiced circumcision and other customs, and chose to worship the Greek deities.

It was a fight for religious freedom, a fight to preserve a people’s right to follow their beliefs; and that’s why it, and no other victory, has a holiday to commemorate it.

King Antiochus IV ascended the throne in Judea, not by succession but by usurpation, in 175 BCE. He was, by all accounts, unstable and given to odd flights of fancy, such as showing up unannounced at the public baths or standing in employment lines for lower-level official positions. Tension between traditional Jews and so-called Hellenized Jews came to a breaking point in 168 BCE. while Antiochus was away on an aborted campaign in Egypt. Riots broke out in Jerusalem between the two factions.

Humiliated and thirsting for blood, Antiochus used the riots as an excuse for a surprise attack on Jerusalem. As the Book of the Maccabees (a chronicle not included in the Bible) described it: “Now when this that was done came to the king’s ear, he thought that Judea had revolted. Raging like a wild animal, he set out from Egypt, he took the city by force of arms, and commanded his men of war not to spare such as they met, and to slay such as took refuge in their houses. There was a massacre of young and old, a killing of women and children, a slaughter of virgins and infants. And there were lost within the space of three days eighty thousand, whereof forty thousand were slain in the conflict; and the same number sold into slavery.” — 2 Maccabees 5:11-14

Antiochus allied himself with the Hellenized apostate Jews and reversed all laws protecting the Jewish faith. All temples were converted to the worship of Zeus and Jewish apostate priests were installed and instructed to sacrifice swine—an unclean animal in Judaism—to the stone idols of the Greeks. All Jewish rites, including circumcision, were banned on pain of death. Antiochus succeeded so well in enforcing a state religion in Judea that he very nearly succeeded in erasing Judaism from the face of the earth. His edicts and actions went unopposed until an old priest, Mattathias of the village of Modin, stabbed his apostate replacement to death as the latter prepared to perform a rite of worship to Zeus.

That single act of defiance by one old man may very well have rescued the Jewish religion from extinction. Mattathias’ five sons escaped with their father to the hills, recruited followers, and under the leadership of the third son, Judas Maccabeus, fought a desperate guerrilla revolt against their oppressors. By 164 BCE, the Greeks and their idol worship were swept from Judea and on the 25th of the Hebrew month of Kislev, the temple in Jerusalem was purified and rededicated. The word “Hanukkah” translates literally as “We dedicated on the 25th.”

The story of the one-day’s supply of oil that lasted for eight is the story of the Jewish people—a culture and a religion whose flame should have flickered out time and time again but kept burning.

Hanukkah is the only Jewish holiday that celebrates a military victory. There were numerous times in the preceding thousand years that the Jews as the nation occupying the Holy Land threw back invaders and threw off the yoke of oppression. None of those victories were crystallized into a holiday.

What made the triumph of the Maccabean revolt different?

Because it was a fight for religious freedom, a fight to preserve a people’s right to follow their beliefs; and that’s why it, and no other victory, has a holiday to commemorate it. As Jewish writer Herman Wouk observed, “It stood out. It was the Jews’ first full-scale encounter with the question that was to haunt them in the next two thousand years: namely, can a small people, dwelling in a triumphant major culture, take part in the general life and yet still hold to its identity, or must it be absorbed into the ranks and the ways of the majority?”

It is a question and a challenge that many other peoples have had to face—the Native Americans, the Amish, and the Muslims in our own country; the Australian aborigines, the Maori of New Zealand; the Sikhs, Christians and Buddhists in India—each a minority in a much larger culture. Sometimes by threat and other times by complacency one may be pressured to surrender one’s beliefs and customs—and therefore one’s spiritual identity—bit by larger bit until nothing is left.

Had the Maccabees failed, of course there would have been survivors to till the fields and tend the vineyards. Of course, people would have lived on, and gone about their business, but Judaism would not have been a part of the picture. It would have vanished from the world stage, an archeological relic to be studied along with so many other long-dead cultures—the Hittites, the Babylonians, the Canaanites, the Sumerians—all gone.

The story of the one-day’s supply of oil that lasted for eight is the story of the Jewish people—a culture and a religion whose flame should have flickered out time and time again but kept burning, despite exile, scapegoating, persecutions, pogroms, holocausts and, in our own day, the soaring statistics of anti-Semitic violence.

That Hanukkah, like Christmas, occurs on the 25th day of the last month of its calendar and thus occasionally collides with and gets mentioned in the same sentence as that holiday is a coincidence of date, no more. The two festivals celebrate utterly different momentous events and yet as Herman Wouk noted are inextricably linked in a way not generally noted.

Wouk wrote: “The two festivals have one real point of contact. Had Antiochus succeeded in obliterating Jewry a century and a half before the birth of Jesus, there would have been no Christmas. The feast of the Nativity rests on the victory of Hanukkah.”

Hanukkah, then, is truly a holiday for all seasons and for all who believe that freedom of religion is worth fighting for, whether that fight involves swords or just the simple insistence that one’s faith is one’s own—not open to forfeit or pawn.