-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

How One Brave Woman You’ve Never Heard of Helped Guarantee Your Religious Freedom

Chances are you’ve never heard of Jane Verin. No great quotes have come down from her, nor have any portraits or observations about her character traits, wit, likes or dislikes. A casting director would be hard-pressed to find a suitable individual to portray her. We don’t know if she was loud and defiant, quiet and submissive, eloquent or illiterate, or modest or immodest. What we do know, however, is her position on an individual’s right to worship as one chooses. We know that she was willing to die for that right. And we know that, in 1638, she became the first woman in the New World to win that right.

Freedom of religion was as alien to people in the 17th century as flying saucers. Consequently, many of those who fled the religious persecution they endured in the Old World to practice their faith freely found themselves, even in the New World, running into the same old phenomena of exclusion of those who were “different.” A case in point was the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Settled in 1628 and governed by Puritans, the colony had no tolerance for non-Puritan faiths, including Baptists, Quakers or so-called Separatists—those who had dissenting views from the Church of England in general and the Puritans in particular.

Jane had defied church elders in Massachusetts Bay by refusing to attend church, and now she defied her husband by continuing to attend church.

Joshua and Jane Verin emigrated from England to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1635, making their home in Salem. But husband and wife disagreed about religion. While Joshua was a Puritan, Jane was a Separatist and refused to attend the Salem church, arousing the ire of the intolerant all-Puritan government, who threatened excommunication and beatings.

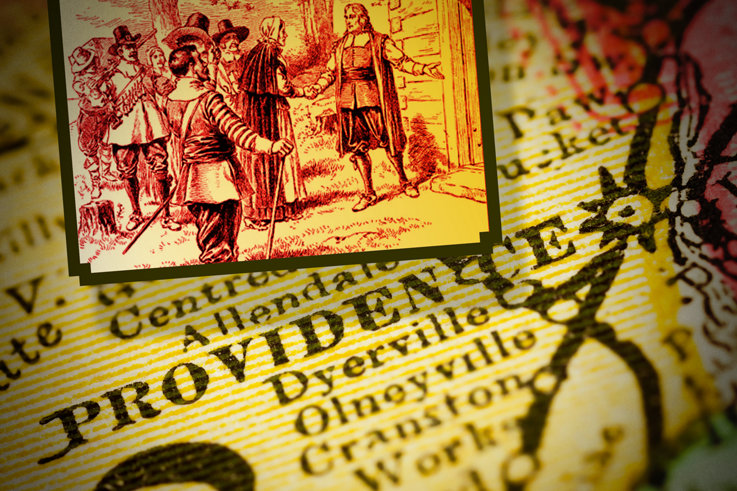

After a year, the Verins moved to Providence, the refuge established by Roger Williams for Separatists and those of other faiths who had endured persecution. Unlike Massachusetts Bay, in Providence, church attendance wasn’t mandatory, so while Jane attended Williams’ open-to-anyone Christian services several times weekly, her husband stayed away without penalty.

We don’t know why Joshua strenuously objected to his wife’s church attendance. It likely had to do with the role of the wife in those days—little more than a servant, expected to obey her husband’s command and cook and clean 24/7 with little or no time reserved for spiritual pursuits. Jane had defied church elders in Massachusetts Bay by refusing to attend church, and now she defied her husband by continuing to attend church. In Massachusetts Bay, Jane risked beatings for asserting her freedom to choose her faith and now she endured them: Joshua beat his wife repeatedly, severely—so much so that it attracted the attention of the elders of Providence, with Williams himself writing that Joshua “hath trodden [Jane] under foote, tyrannically and brutishly” and that “with his furious blows she went in danger of Life.”

The matter was brought to the 50 colony leaders of Providence. There was no issue that a husband had the perfect right to assault and inflict bodily harm on his wife. Still, the fact that he was doing so to prevent her from exercising her freedom of conscience was a serious enough matter to be brought to trial. Joshua’s supporters argued on behalf of his freedom of religion, which allowed him to exercise his belief that God’s will decreed that a wife must obey her husband in all things—or else suffer the consequences. But John Green, a prominent member of the community and one of the founders of Providence, wisely countered that allowing a man to beat his wife over a matter of conscience could spark mutiny from all women.

In the end, on May 21, 1638, Joshua Verin was found guilty and disenfranchised—not for nearly killing Jane, but for the crime of “breach of a covenant for restraining of ye liberty of conscience.” Unrepentant, Joshua promptly moved his family back to Salem in Massachusetts Bay, where Jane again ran afoul of the law by refusing to attend the mandated church. The last we hear of her is a notation of her expulsion from the Salem church on January 7, 1640.

But Jane Verin had done something no one else had done. Historian Margaret Manchester writes that Joshua Verin’s trial and verdict “appears to be the first time that a wife’s liberty of conscience, independent of her husband’s, was upheld in the English colonies.”

“Women of the Puritan time were thought of as servants of their husbands,” wrote legal scholar Edward Eberle. “Viewed against this backdrop, recognizing a woman’s independence was an unprecedented act for the time and a forward-looking vision of things to come.”

As a direct result of Jane’s courage and the verdict in her favor, a new pattern was set in the New World. Mindful of this, two years later, in drafting the new Providence Agreement—a legally binding document on all voting members of the community—Roger Williams and his fellow elders included the requirement “to hold forth the Liberty of Conscience.”

Providence’s acknowledgment of the existence of “liberty of conscience” inspired later generations, including Jefferson and Madison, to center our own form of government on the fundamental human right of religious freedom.

And all because of a stubborn woman with integrity—all but forgotten today—whose insistence that her conscience was worth as much as anyone’s earned her a day in court and a victory for us all.