-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

I’m a Scientologist. I’m a humanitarian. The bigotry has got to stop.

I remember when I first became aware many years ago that there was a Wikipedia entry about me. It seemed, back in the burgeoning digital age, like having your very own Wikipedia entry was some kind of stamp of legitimacy—that you were now officially “relevant.”

As I read the short entry, I was struck by the fact that it was at least 50% incorrect. It’s a weird experience to read about your supposed life written by people who’ve never met you and obviously don’t have all their facts straight. But I learned you can’t just go in and edit your own Wikipedia entry so I laughed it off, reminding myself that the sun would almost definitely rise the next morning despite the fact that my personal Wikipedia article wasn’t God’s gift to literacy or accuracy.

Recently I happened on that same entry again but this time there was a new paragraph. It talked about my nonprofit foundation, Rock For Human Rights, of which I’m enormously proud. I was happy to see it mentioned. But then it said it was a group “supported by the Church of Scientology and affiliated with Youth For Human Rights International and Citizens Commission on Human Rights, both described as Scientology front groups.”

There’s so much to unpack there I hardly know where to start. To begin with, my church supports me and my activities the way they support literally hundreds of thousands of other volunteers all around the world who are doing amazing work in the field of human rights, drug education, literacy and other nonpartisan, nonpolitical humanitarian work. I have never received financial support from the Church for my nonprofit work but they have been extremely generous in supplying human rights education materials in multiple languages which have allowed me to help educate and enlighten tens of thousands of youth all over the world.

It’s a weird experience to read about your supposed life written by people who’ve never met you and obviously don’t have all their facts straight.

Rock for Human Rights is affiliated with Youth For Human Rights in the sense that we’re using the educational materials they generously supply. (That that sort of partnership could in any way be construed as negative is baffling to me.) Finally, although I admire and respect what Citizens Commission on Human Rights does, Rock for Human Rights is not affiliated with them.

The idea that my group or these other amazing groups are “front groups” for my church is a great example of how the work my church does, as well as the work individual Scientology parishioners themselves do, often gets lumped together in a mishmash of misinformation or outright falsehoods that make it sound like there’s some ulterior motive or agenda to helping people.

Such minor monuments to bigotry take the countless hours of volunteer work done by so many people I admire (volunteer work, as in doing everything else you have to do to pay your bills and spend time with your family and walk your dog and hopefully enjoy a few hobbies and in addition to all of that carving time out of your schedule—and often your own wallet—to do work you hope will contribute to making the world a better place) and tries to distort it into something other than the genuine, heartfelt effort to uplift others that it truly is.

My church is many wonderful, fascinating and unique things, but no one could ever accuse us of being shy. We proudly and openly share our beliefs and offer our help to people all over the world, people of all faiths and creeds who only have in common a desire to understand themselves and life better. We don’t need “front groups” because we don’t have anything to hide, ever. There are thousands of groups around the world that are affiliated with Scientology and Scientologists.

But one thing that I find all the Scientologists I know have in common is a deep-seated belief that every person is worth helping and that there are genuine solutions to every problem we face as individuals and as a society. This quality, this desire to help others that comes from the best possible place, should be celebrated, not distorted or used to denigrate my church and its parishioners. To do so is pure hate. It is also often a concerted effort on the part of vested interests who benefit from a less-than-perfect status quo, and a small minority of people who are themselves so degraded they find the idea of truly helping others repulsive, even threatening.

This quality, this desire to help others that comes from the best possible place, should be celebrated, not distorted or used to denigrate.

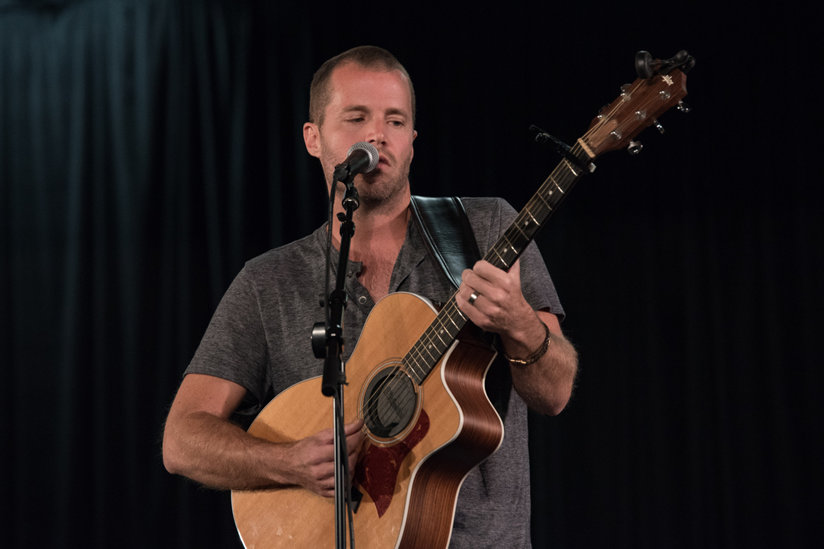

I think about the hours I’ve spent on airplanes, in vans and trains and taxis, lugging music equipment and (not) sleeping in cheap motels, so I can spend time with kids all over the world and tell them how absolutely amazing they are, how they have the power within themselves to create a future world so ideal that it seems like magic compared to how we live now.

I think of the countless messages and testimonials we’ve received from many of those same young people detailing the life-changing realizations they’ve had after attending our performances and hearing us speak. And then I think about that five-paragraph Wikipedia entry, carefully laden with the “polite,” “dispassionate,” “academic” (and therefore supposedly inoffensive?) language that is straight-up bigotry—the kind of “reasonable” sounding hate speech to which my church and its members like me are so often subjected. I’m putting so much of that sentence in quotes to spotlight what hate speech too often sounds like in 2021; it doesn’t come with torches and pitchforks, shouted by angry voices. It comes swaddled in the language of “objectivity,” whispered in the ears of well-intentioned people who don’t know they’re being misled. It’s a knife in the back rather than a sword at the throat.

I know who I am. I know what drives and motivates me and why I do the things I do. I am proud and grateful to be a Scientologist. But my church doesn’t need my or anyone else’s help telling the world what Scientology has to offer.

They’re doing an extraordinary job of that all on their own.