-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

In Honor of Equality, This Human Rights Day

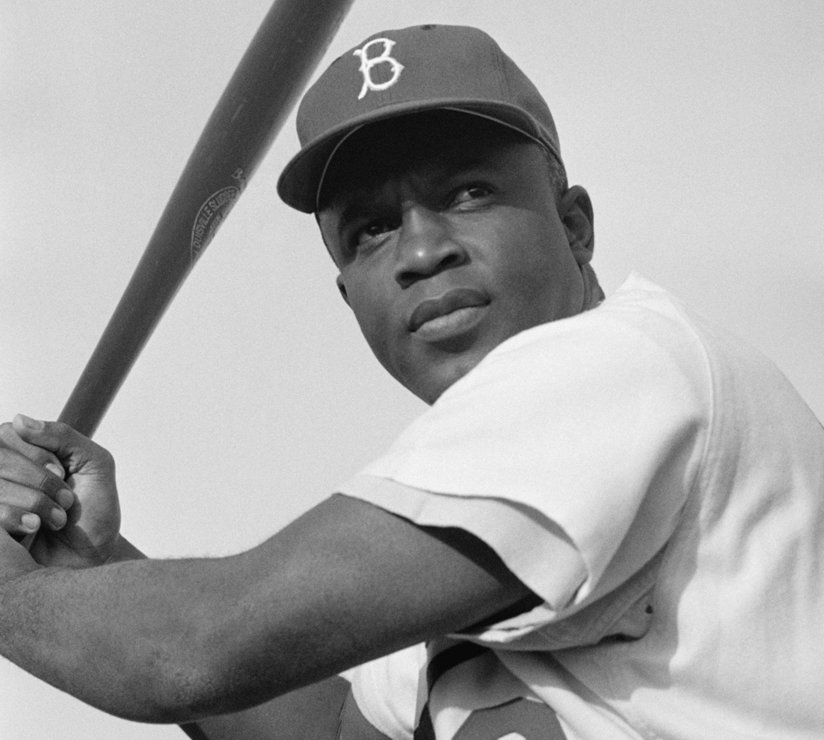

Accompanied by his wife of three weeks, Jackie Robinson was waiting in a Los Angeles airport to board a plane to Daytona Beach, Florida. He was going there to try out for the Montreal Royals, the minor league affiliate for the Los Angeles Dodgers. The date was February 28, 1946.

For the previous five years, Black men had fought and died for freedom in Europe and the Pacific. Now, returning home, they continued to fight and die. Florida, where the Robinsons were headed, was still the deep south, a region where the Ku Klux Klan rode at night and where more Black men had been lynched per capita than any other state in the Union. Just 16 days before the Robinsons’ flight, Isaac Woodard, a returning Black veteran, had been forcibly removed from the bus that was taking him home and beaten so badly by a sheriff that he was left permanently blind. North of Florida, in Tennessee, just three days before, a crowd of Black men had rioted in protest of racial discrimination. Dozens were arrested. Two were shot while under arrest.

Newspaper coverage of these events would have surely been on their minds as they boarded their plane.

When they landed in New Orleans, Rachel Robinson disembarked to use the restroom. The first restroom she saw was labeled “Whites Only.” The Robinsons were then prohibited from reboarding the plane, which took off without them. While awaiting another flight, they were denied entrance to the airport’s whites-only restaurant. Finally, they boarded a plane that was to take them to Daytona Beach, but when it stopped in Pensacola to refuel, the Robinsons were told to leave. Two white people took their place.

For the previous five years, Black men had fought and died for freedom in Europe and the Pacific. Now, returning home, they continued to fight and die.

Unwilling to wait for another plane, they boarded a Greyhound bus. At the first stop, the driver ordered the “boy” and his wife out of their seats and to join the rest of the negroes at the back of the bus.

Finally, Jackie Robinson arrived at Daytona Beach and began the desegregation of baseball, and by extension American society.

He was not alone. In India, Mahatma Gandhi was about to achieve independence from England for his native India, although the resulting religious and nationalistic turmoil would claim his life within the year. In South Africa, a young Nelson Mandela was studying law and organizing Black youths to protest apartheid, unaware that 20 years of prison lay ahead of him.

Help was coming.

Responding to, among other things, the Isaac Woodard beating, President Harry S. Truman established a federal Committee on Civil Rights. One of its first recommendations was a federal law to protect the voting rights of Southern Blacks and provide federal protection against lynching. Rosa Parks was still almost 10 years away, and the legislation was defeated. The Committee disbanded in 1947, but the winds of change were gathering.

On December 10, 1948, the United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). The UDHR is a milestone document which predates the 1957 formation of the United States Civil Rights Commission by almost a decade. The UDHR proclaims the inalienable rights that everyone is entitled to as a human being—regardless of race, color, religion, sex, language, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. It is available in more than 500 languages, making it the most translated document in the world. The full text of the declaration can be found here.

The UDHR proclaims the inalienable rights that everyone is entitled to as a human being.

In commemoration of the UDHR’s adoption, the United Nations has established December 10 annually as International Human Rights Day. In recognition of the day’s importance, it is also the day on which the Nobel Peace Prize is awarded.

Each year, the day carries a theme. This year, that theme is “Equality” as spelled out in Article 1 of the UDHR: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.”

But freedom does not come by declaration alone. It has to be demanded, fought for, and won. Thanks to the many who fought and sacrificed, the United States, indeed the world, is a far different place today than it was when Jackie Robinson traveled to Daytona Beach back in 1946.

But there is still a long way to go.

When we celebrate Human Rights Day, we celebrate those who have fought, and we encourage and support those who continue to fight.

That fight can be as large as a lawsuit, as loud as a street protest, or as muted as simply saying “no.” I know. In my almost 50 years in Scientology, I’ve been involved in all of the above. My friends have their tales to tell, too. That’s what STAND is all about. We’re working to create a safe environment so that every Scientologist, whether in a crowd of thousands in Clearwater or in a small gathering in Idaho, can practice his or her religion in security and peace.

As Eleanor Roosevelt stated in 1951: “Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home—so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world. Yet they are the world of the individual person; the neighborhood he lives in; the school or college he attends; the factory, farm or office where he works. Such are the places where every man, woman, and child seeks equal justice, equal opportunity, equal dignity without discrimination. Unless these rights have meaning there, they have little meaning anywhere. Without concerted citizen action to uphold them close to home, we shall look in vain for progress in the larger world.”