-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

In Previously Unheard Tapes, Adolf Eichmann Incriminates Himself as the Architect of the Holocaust

“Everything recorded and transcribed here should be stored. Only when I die it is my wish, may it serve as the basis for scientific research. But in no uncertain terms: I don’t wish to come out of the shadows into the light.”

— Adolf Eichmann, 1957

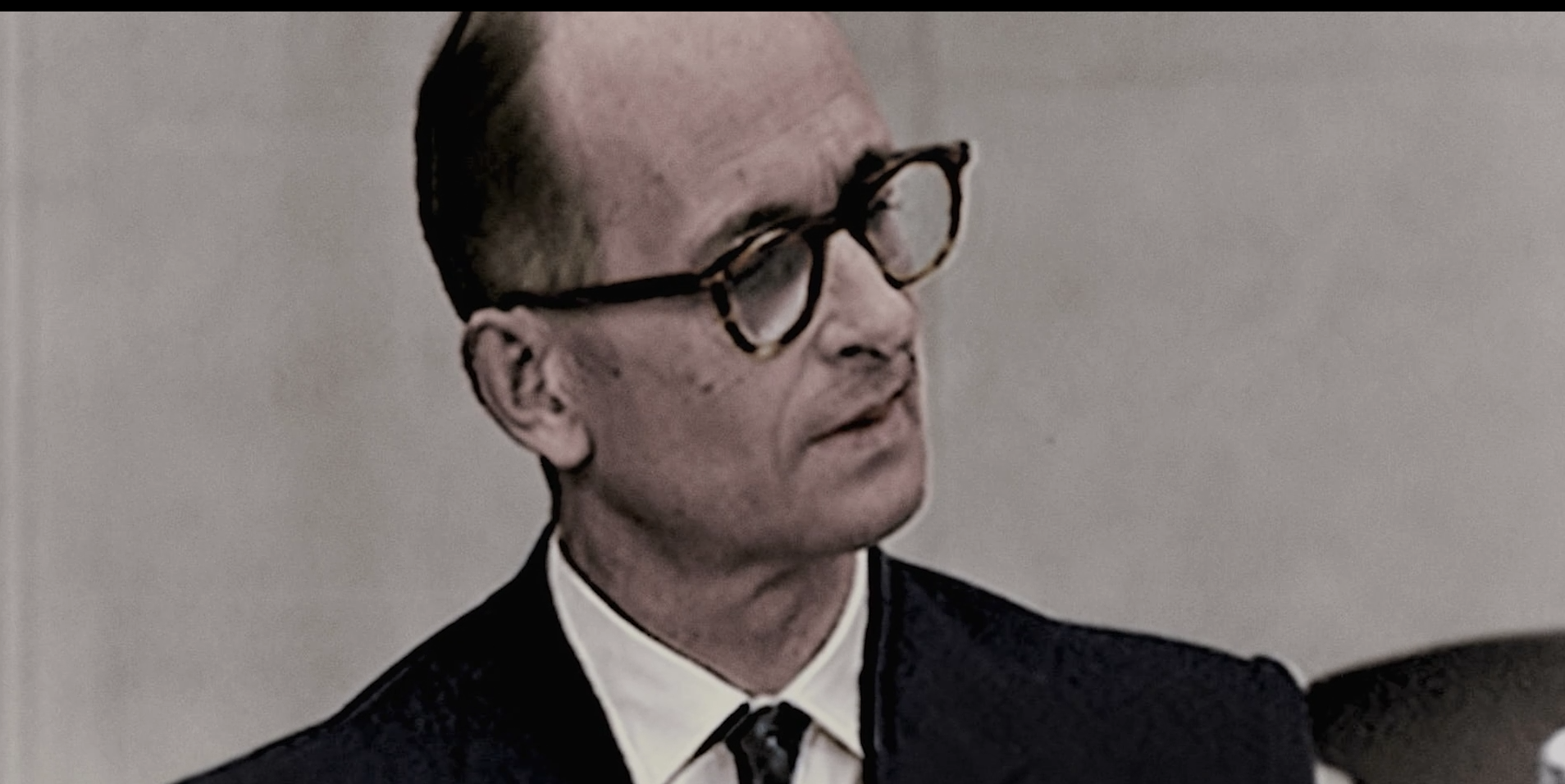

The rumpled, bespectacled man in the glass booth seemed incapable of causing harm to a flea, let alone the cold-blooded murder of six million human beings. Yet Adolf Eichmann, a little man made smaller still by a suit at least a size too large on him, was determined to make himself look innocuous, no more than a low-level clerk in a colossal machine as he stood accused of being the master architect of the greatest crime in history—the Holocaust.

Eichmann denied all the accusations. He denied knowing that the trains he dispatched to Auschwitz contained human cargo marked for extermination. He denied seeing any killing or torture and denied knowing of or hearing of any such thing. “I was sitting at my desk in Berlin,” he protested, “and had nothing to do with it,” his demeanor emotionless, save for a perpetual smirk twisting the left side of his face.

Eichmann denied any responsibility for the Holocaust, protesting his innocence and ignorance up until his death by hanging after an Israeli tribunal found him guilty in 1961. But four years earlier, he sang a different tune in a series of taped conversations that have now been made public and are dramatized in the three-part Amazon Prime docuseries, The Devil’s Confession: The Lost Eichmann Tapes.

“I didn’t even care about the Jews that I deported to Auschwitz. I didn’t care if they were alive or already dead,” Eichmann brags to Nazi journalist Willem Sassen in a notable excerpt from the dozens of recorded hours that amount to a full confession, including names, dates and details of how he personally masterminded and coordinated the Final Solution, carrying out each grisly step with gusto.

Eichmann, relaxed and holding court on the tapes, proves to be a calculating and brutal individual delighting in what he did best: murdering Jews.

Eichmann was a big man in the Nazi community of Buenos Aires, the safe haven sheltering many adherents of the Master Race who had fled when the Third Reich crumbled. He was recognized as a former high official and made no attempt at concealing his identity. He enjoyed the spotlight, enjoyed being regarded as the “Jew expert.” And with Sassen he spoke freely, enjoying reliving what to him was the happiest time of his life.

To the expat Nazis, the mass murder of the Jews was a lie that never happened. In Eichmann, journalist Sassen felt, he had an eyewitness, someone who could tell him right out, with facts and figures, that the genocide never happened. He was to be bitterly disappointed. His interviewee was proud of his life’s work: the murder of Jews.

Eichmann continues, “There was an order from the Reichsführer [Heinrich Himmler] that said Jews who are fit to work must be submitted to the work process. Jews who are unfit to work had to be submitted to the Final Solution. Period.”

There’s a brief pause, followed by Sassen asking, carefully, “And with that, you clearly and openly meant physical extermination?”

Eichmann answers, “If that’s what I said, then yes. Obviously.”

There’s a longer pause. An unidentified voice murmurs, in German, “We can’t do this. We can’t do this.” The tape shuts off, then clicks back on again. Sassen continues recording even though he knows Eichmann will not deny the Holocaust nor his role in it.

The docuseries switches back and forth between the little man in the glass booth protesting his innocence to the braggart contradicting himself four years earlier, sometimes almost to the exact line. At the trial he says he knows nothing of any plans to transport Jews, says he’s not an antisemite. On the tapes he details the logistics needed to transport five trainloads of Jews to Auschwitz and death. Sassen’s wife interrupts, apologizing for not being able to procure any more cigarettes right now. Eichmann gallantly says, “Thank you so much for trying, dear lady. No worries at all.” And then resumes bragging how he got a whole city Judenfrei in record time. In the background you can hear Sassen’s children playing and singing.

Filmmakers Yariv Mozer and Kobi Sitt weave their chronicle through archival footage of the young Eichmann in full uniform, intercut with clips of the 1961 trial and interspersed with modern footage of actors lip-syncing the German of Eichmann and Sassen. What emerges is not what writer Hannah Arendt—present at the trial and watching Eichmann act the part of the harmless little bureaucrat—called “the banality of evil.” On the contrary, Eichmann, relaxed and holding court on the tapes, proves to be a calculating and brutal individual delighting in what he did best: murdering Jews.

The tapes’ existence were known about at the time of the trial—Sassen had sold excerpts of the transcripts to Life magazine just months before. But the location of the tapes themselves remained a mystery until the 1990s. Consequently, the Israeli tribunal would not admit the transcripts as evidence, and the prosecution was forced to use other means instead: witnesses—Holocaust survivors who had themselves come in contact with Eichmann and experienced firsthand his cruelty and his hate.

To a new generation, the Eichmann tapes provide invaluable history and, as Mozer said, “This is proof against Holocaust deniers and a way to see the true face of Eichmann.”

The prosecution presented its final evidence against Eichmann. The lights in the court went out and those in the court saw a film compilation of atrocities and torture, of dead bodies bulldozed, of men, women and children herded like cattle to their deaths. In the control booth, the TV director, himself a Holocaust survivor, trained a shot on the accused as he watched the footage. In what he thought was the anonymity of darkness, the little man permitted the smirk on his face to broaden into a smile.