-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

STAND Member Reflects on Visit to Iconic Religious Freedom Site

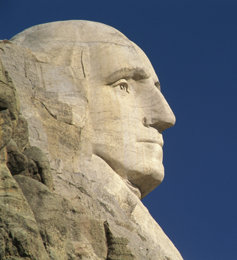

“To Bigotry No Sanction” George Washington

Under cover of a January blizzard, Roger Williams left his wife and children, slipping away to avoid the men sent to arrest and deport him for what Puritan leaders in Massachusetts had called “dangerous” religious beliefs. With punishment awaiting him in England that included life imprisonment or death, Williams sought refuge in the bitterly cold wilderness, protected by the deep snows that thwarted pursuit.

For much of that 1636 winter, the great Wampanoag leader Massasoit provided shelter to Williams, who ultimately settled some 55 miles south and west of Salem, on the far side of Narragansett Bay. Buying land from the Narragansett tribe, he named his new home Providence and declared that anyone living there would be free to worship as they chose.

His family and others whose beliefs might bring persecution—including Baptists, Jews and Quakers—joined him in this unique haven. In 1663, a Royal Charter signed by King Charles II gave to the colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations the guarantee “that no person within the said colony, at any time hereafter, shall be any wise molested, punished, disquieted, or called in question, for any differences in opinion in matters of religion” and that “all and every person and persons may … freely and fully have and enjoy his and their own judgments and consciences, in matters of religious concernments….”

While the colony had been home to many Jews since the mid-1600s, it also became home to the oldest Jewish place of worship in the 13 colonies still standing with the dedication of Touro Synagogue in Newport in 1763.

When the Constitutional Convention gathered in Philadelphia in May 1787, Rhode Island again showed its independence by boycotting. And when the Constitution was put to a vote, the state’s citizens initially rejected it by a margin of more than 10 to 1.

Rhode Island’s spirit was evident when it became the first colony to declare independence from England on May 4, 1776—two months before the Declaration of Independence.

When the Constitutional Convention gathered in Philadelphia in May 1787, Rhode Island again showed its independence by boycotting. And when the Constitution was put to a vote, the state’s citizens initially rejected it by a margin of more than 10 to 1.

It was not until May 1790 that Rhode Island finally passed the Constitution, the last colony-turned-state to do so.

Three months later, on August 17, President George Washington arrived in Newport, accompanied by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, Supreme Court Justice John Blair Jr., New York Governor George Clinton and others.

The visit served to acknowledge Rhode Islanders for voting in favor of the Constitution and also for approving, in June 1790, 11 of the 12 articles of the original Bill of Rights, passed by Congress in September 1789.

During the visit, Moses Seixas, leader of Newport’s Jewish congregation, read a letter to Washington that stated, in part:

Deprived as we heretofore have been of the invaluable rights of free Citizens, we now with a deep sense of gratitude to the Almighty disposer of all events behold a Government, erected by the Majesty of the People—a Government, which to bigotry gives no sanction, to persecution no assistance—but generously affording to all Liberty of conscience, and immunities of Citizenship: deeming every one, of whatever Nation, tongue, or language equal parts of the great governmental Machine….

In his response, Washington included these words:

The citizens of the United States of America have a right to applaud themselves for having given to mankind examples of an enlarged and liberal policy — a policy worthy of imitation. All possess alike liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship.

It is now no more that toleration is spoken of as if it were the indulgence of one class of people that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights, for, happily, the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.

While Washington’s letter has been variously dated between August 18 and August 21, no doubt exists as to its sweeping implications, establishing an enlightened tone for the new government and the new nation, and setting a high bar for humanity—unfettered, unhindered freedom of religion and freedom of thought for all.

Sixteen months later, in December 1791, the Bill of Rights would be formally adopted.

The unique venue that inspired the first president to articulate his pledge stands today, magnificently preserved and open to visitors, in downtown Newport. State-of-the-art displays spotlight key events in the history of the synagogue, the city and the state. And each year, a reading of Washington’s letter takes place there. This year’s ceremony was on Sunday, August 20.

Photos by: LEE SNIDER PHOTO IMAGES / Jack Boucher / Shutterstock.com