Marin Alsop Conducts the Music of Tolerance

Music is universal. Everyone understands it. Tragedy and joy may bring us together at times, but music is always there as witness and participant, uniting us without pretext, pretense or reason why—no matter what we look like or what we believe, no matter where we live or how we dress, regardless of our opinions or whether or not we’ve had a good day.

Music makes a lie the notion that we are different from one another, that there are boundaries that separate us, and walls that divide. Music demonstrates firmly, finally and lovingly that what divides us are wisps of nothing, vagrant thoughts that can be brushed away. Music demonstrates that we are all worthy, that we are all special, that we are all deserving.

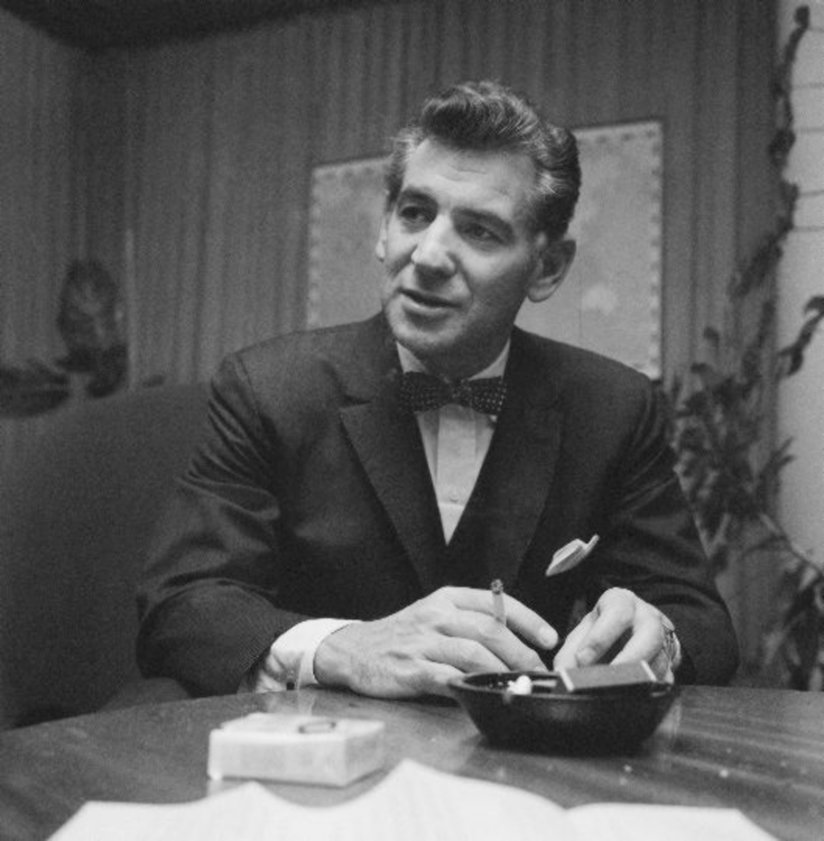

Marin Alsop attended her first Leonard Bernstein Young People’s Concert at age 9. The maestro conducted with his usual verve and passion, pausing to address his audience: “My dear young friends… What is a conductor, anyway? Why do these fine musicians need one?... Mahler, of course, was a grown-up, but I believe his music is best understood by children. By you.”

This magical person was not only filling an enormous room with what sounded like the music of heaven, but he was then turning and speaking, it seemed, directly to her. She announced to her father, himself a professional musician, “THAT’S what I’m going to be! A conductor!”

Excited and thrilled, she made the same declaration the following day to her violin teacher, who promptly shot it down: “Girls can’t do that.”

Juilliard refunded her $35 application fee.

Crushed, she informed her father what her teacher had said. Visibly upset, he left the room. The following day Marin awoke to find a present from him: a long wooden case containing more than a few conductor’s batons.

Her father was in the minority. After years of music study, Marin applied as a conductor at the Juilliard School, one of the most prestigious performing arts conservatories in the world. She made it all the way to the final round. Auditioning, she was amazed to discover the committee had arranged for certain musicians to play the wrong notes to make her look bad. “I can’t believe they made you play that note,” Marin tried to joke, eliciting awkward laughter from the musicians who had been put up to it, but the damage had been done. The committee had succeeded in making her, their one female applicant, look bad, and she was not accepted.

She applied yet again, and this time the conducting teacher informed her, “You will never be a conductor. Your muscles have atrophied.” She was 23. “Maestro,” she begged. “If you take me on, I promise you, I will be the best student you have ever had.”

The teacher looked at her for a cold moment, then said “No.”

Juilliard refunded her $35 application fee.

People didn’t seem to understand that for Marin this was life—what she was meant to do. The insane thought crossed her mind to simply start her own orchestra. After all, she had already put together a women’s string band. How difficult would it be to put together 50 more people and call it an orchestra?

She contacted a wealthy businessman, Tomio Taki, for whom her band had performed at a private function. Over drinks, she outlined her plan.

As Mr. Taki recalled later, “I said, ‘Why not?’ In my opinion, anybody can do anything. Women, men, Black, Oriental—who cares?”

With the newly minted and funded Concordia Orchestra, Marin was able to showcase herself and her abilities on her own terms. She attracted the attention of the press and the favorable notices of audiences and music critics. Was the future face of orchestral music a woman?

It was a statement that turned out to be an apology, issued in advance, on behalf of his colleagues in the music world.

She again auditioned for a conducting program, this time at Tanglewood Music Center, an annual summer music academy in Lenox, Massachusetts. On her fourth attempt, she was accepted, where she was taught by her hero, Leonard Bernstein.

Bernstein believed in her, embraced her passion, and cheered her every performance at Tanglewood. One night, however, he remained quietly in his seat, his eyes closed. Marin asked him what was wrong.

“I just don’t get it. I just don’t understand,” the old man murmured. “When I close my eyes I can’t tell you’re a woman.”

It was a statement that turned out to be an apology, issued in advance, on behalf of his colleagues in the music world.

Because the attacks soon began. When the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra (BSO) hired Marin to take the baton for its 2006-2007 season, marking the first time a major American orchestra would be led by a woman, the backlash was immediate and savage.

Letters, both anonymous and signed, poured into the BSO: “This appointment will bring 36 years of progress to a halt.” “Why are you getting her when all these other qualified people are out there?” “I can’t watch a woman moving her rear end around up there—it’s just too distracting.” “The funding will trickle off.”

Other conductors weighed in: “A sweet girl on the podium can make one’s thoughts drift toward something else.” “Women on the podium are not my cup of tea.” The BSO’s own retiring conductor told the Baltimore Sun, “It’s counter to nature.”

A letter fabricated by a few members of the orchestra detailed a list of accusations—all false—against Marin, with the result that the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra’s Player’s Committee issued a statement that read, in part, “The orchestra members are unanimous in their view that the search process should continue.”

For a time, Marin seriously considered caving to the pressure and withdrawing her appointment, then realized doing so would only place the same burden on any future aspirant seeking to shatter the glass ceiling.

“We want to apologize. You have our support.”

Marin arranged to meet with the orchestra before their next rehearsal, alone, without the presence of board members and executive staff of the BSO.

Speaking from the heart and as a fellow music lover, she outlined her vision for the orchestra—of bringing them to the next level of excellence. It had been many years since the symphony had made a recording. Her intention was to end that famine.

Most importantly, though, there needed to be a connection with the community. Baltimore was a city of marginalized people, crime, and poverty. It was Marin’s belief that the city’s own orchestra must take a measure of responsibility for improving those conditions.

After a pause, the chairperson of the Player’s Committee stood up and said, “We want to apologize. You have our support.”

That put an end to the controversy. With the support of the orchestra, there was no question as to Marin wielding the baton. And wield it she did. Under her leadership as Music Director—and as the first woman to lead a major American orchestra—the BSO did reach the next level of artistic excellence and did make recordings again. And, true to her word, they reached out to the community with Marin’s program, OrchKids, a year-round, during- and after-school music program designed to create social change and nurture promising futures for youth in Baltimore.

Starting with 130 children from an underserved school and now serving over 1,900 youth, OrchKids provides opportunities for young people who might otherwise be passed over. They receive lessons, snacks, tutoring and mentoring and achieve music skills as well as character building, confidence, and self-respect. The program, which began in 2008, has now been around long enough to see a number of its graduates go on to study music at a higher level.

Marin Alsop’s life could be likened to a symphony.

For Marin Alsop, the circle is complete. From having to overcome her own slammed doors, she now opens them for others. Of OrchKids, she says, “I’m more proud of them than anything else I’ve ever done. Not that I did it. They did it. The one thing I never want to do to a young person is to tell them, ‘You’re not something,’ ‘You can’t do something.’ And for me that’s the worst four-letter word ever invented: can’t.”

Marin Alsop’s life could be likened to a symphony. The first movement is brisk and energetic with her purpose in full and radiant view. The second is slower, as blocked opportunities manifest, all the while gaining wisdom and experience in preparation for the battle to come. The third movement is a spirited dance filled with surges and retreats, insistences, and counterpoints as she battles for recognition and acceptance. Then at the last, the fourth movement—wherein all the earlier themes of her life return—working together now to bring forth a final and rousing victory, the door flung open for a bright future for all, no matter their race, gender or place of birth.

With her example, her persistence, and most of all through OrchKids, Marin has created a connection and a hope now for everyone through music, which communicates, as she puts it, “the unspoken beauty of what we can have when we connect as human beings.”