-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

Monsters in Crayon: One Man’s Drawings of the Time He Spent With Architects of the Holocaust

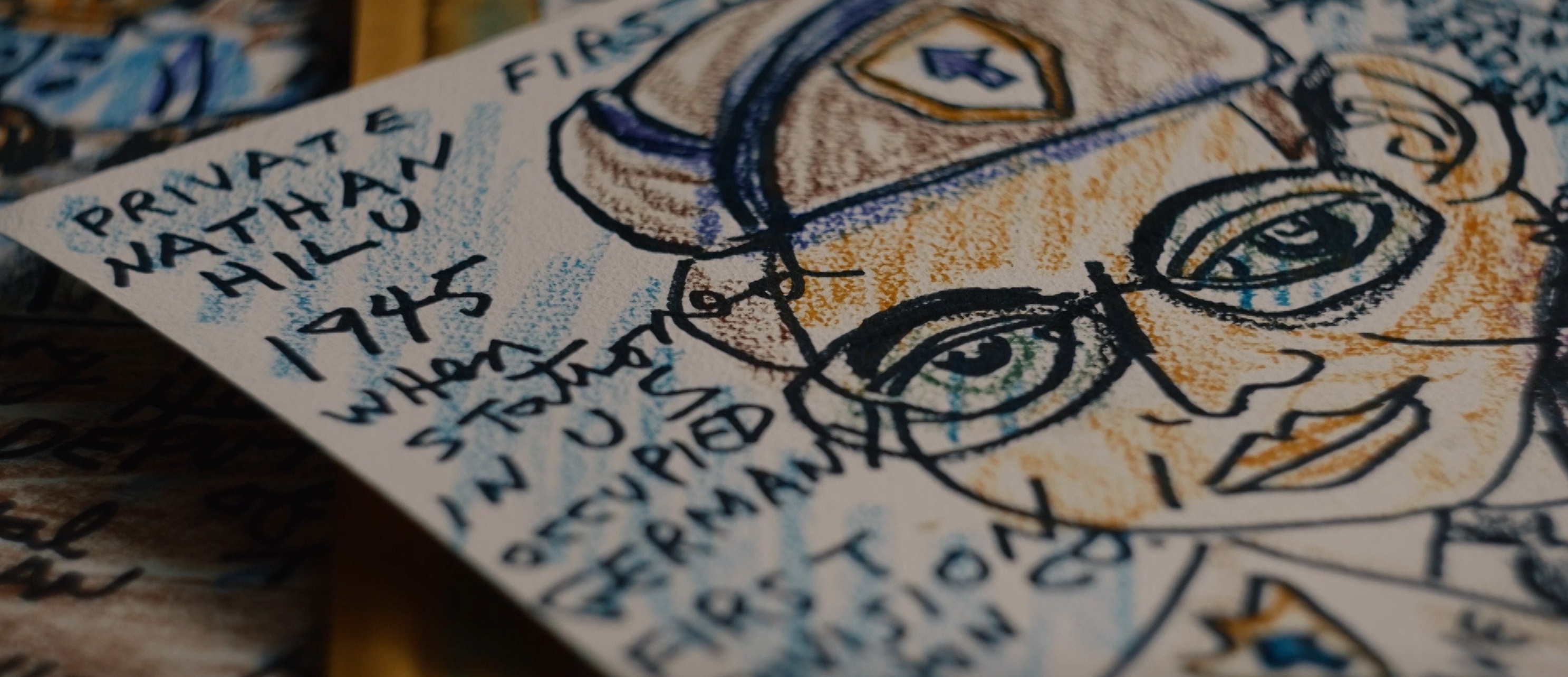

The pictures are scrawled in crayon and Sharpie with glued-on scraps of scissored construction paper. The captions are hasty, the letters and words tumbling over each other as if fighting to get off the page. The artist, Nathan Hilu, age 93, is in a hurry. He paints, pastes, scribbles and handwrites his artwork as he talks to the camera, to the interviewer, to anyone who will listen.

Over the decades he has produced truckloads of this artwork.

Why the frenzied output? Why the obsession?

Because Nathan Hilu has a story to tell, and through the lens of filmmaker Elan Golod, we become a party to that story as told in the new documentary Nathan-ism.

“My life produces my art.”

In late 1945, 19-year-old Private First Class (PFC) Hilu was assigned to guard the top Nazis of the Third Reich, the architects of the Holocaust, answerable to the Fuhrer himself—now prisoners in Nuremberg, awaiting their trial for war crimes.

What Hilu experienced is unique. “You have all these Nazis,” he says in the film. “They helped Hitler kill 6 million Jews in the Holocaust, and I, a Jew, helped punish them.”

The army’s main concern about the captured Nazis was not that they would escape, but that they would commit suicide before justice could be done. Such was the fate chosen by the likes of Hitler, Himmler, Goebbels and other high-ranking Nazis who preferred death by their own hand over defeat.

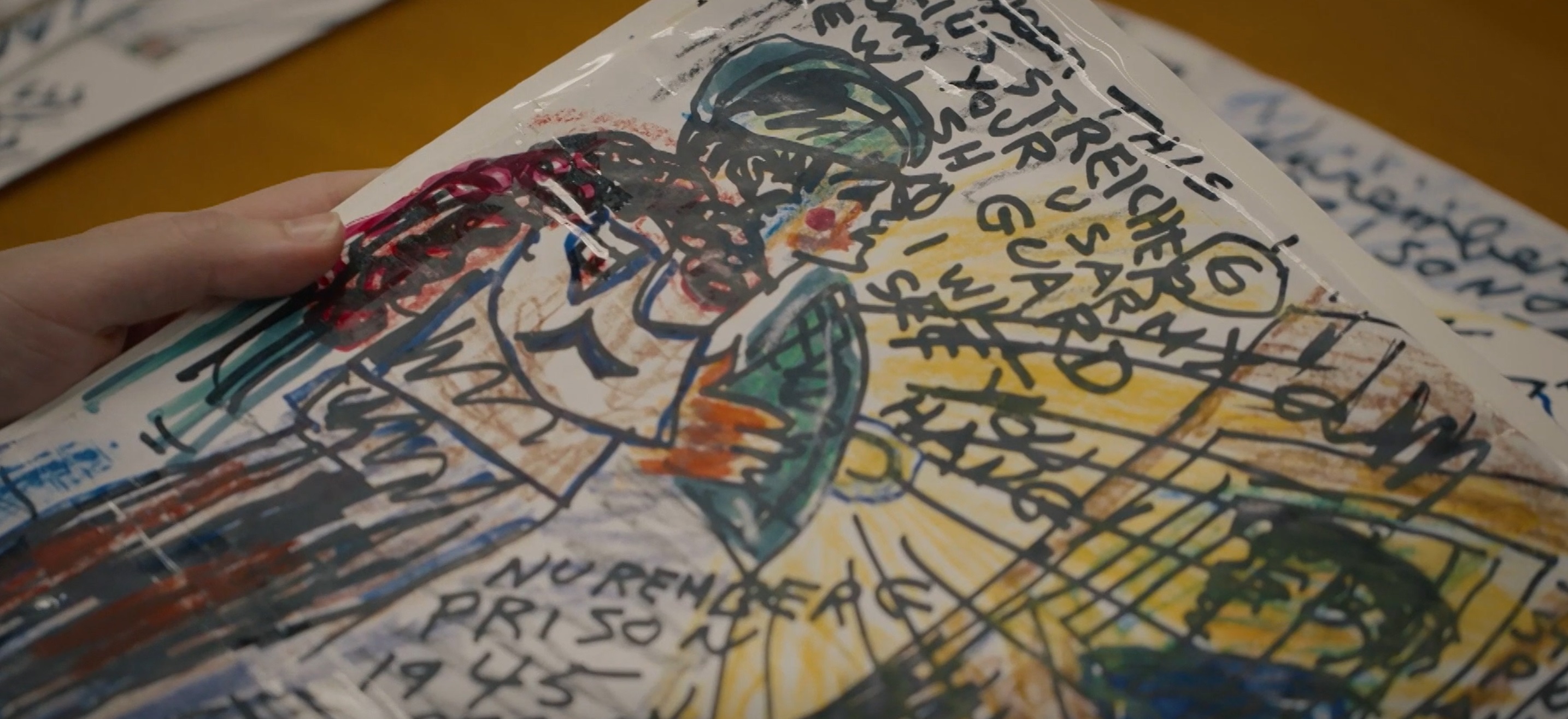

Accordingly, prison guards were equipped with floodlight lamps trained through the cell bars and on the prisoners themselves 24/7. Hilu’s painting illustrates this in a re-creation of his first encounter with Hermann Göring. In bright colors, we see Göring, the second most powerful man in the Reich, peering through his cell at the floodlight manned by Hilu who glowers at him. Written over the picture is, “Now hear this, Field Marshal Hermann Göring. I, PFC Nathan Hilu, an American Jewish GI soldier, am now in charge.”

Many Holocaust survivors, as well as those who experienced battle, those who endured privation and those who served directly under the puppeteers of the war, have crystallized their memories in print. Libraries are full of personal accounts of the tattered years from 1933 to 1945. But Nathan Hilu’s “memoir” is his artwork—a visual memoir. “My life produces my art,” he says.

Nathan Hilu

Another rendering shows Nazis at prayer on Christmas 1945. “They took a couple cells and made them into a chapel,” Hilu recalls. “They sang all kinds of German songs. Göring sang those songs. He sang so sweetly. I said, ‘How could it be? He is the one who ordered the final solution.’”

Hilu is an outsider artist, a label attached to a creator who has no genre, no definable style, no classic fine arts education—if indeed any at all—and who simply creates.

Nathan Hilu was charged with shining a spotlight into the cells of Nazi criminals.

Laura Kruger, curator of the Hebrew Union College Museum and a champion of Hilu’s work, says, “Outside of the art world, embedded in the culture, there are under-known people who will make the work whether there is anyone looking at it [or not].”

When Kruger encountered the myriad notebooks covered with memories of Nazi prisoners and the Nuremberg trials, her first impression was that they were “almost childlike drawings very rapidly drawn with markers or crayons. It was not until I started getting deeper into his work that I realized what this is about.”

Art journalist Jeannie Rosenfeld, another who believes in Hilu’s work, tells the interviewer, “Hilu has operated beneath the art world radar, creating powerful artworks which erupt like a stream of consciousness. I just felt really deeply that this artist deserved coverage. It’s unlike anything I have ever seen. And yet he’s an unknown.”

Golod intersperses shots of the aged but driven Hilu and his works with documentary footage of Nuremberg. Drawings of the cellblock fuse with photographs and some of the artist’s sketches of Nazis are animated, giving a curious cartoon-like life to the faces of evil.

One watches the film and its healthy helpings of Nathan Hilu’s art and is left with the impression that these Nazis—these men who oversaw the slaughter of millions without a scintilla of remorse—these were not towering monsters, but weak two-dimensional ciphers, incapable of the strength required to summon up even a teaspoon of integrity or self-respect.

Or as Hilu—who saw them stripped of their flashy uniforms and cowering in their cells—described them: “They were no supermen. They were all little schleppers.”

Nathan Hilu did not live to see the documentary completed. In a voicemail to the director we hear him say, “Hi Elan. I don’t feel too good. Can you come over?” During the eight years that it took the Israeli-American filmmaker to first win the reclusive artist’s confidence and then put together the documentary, its subject continually says, all the while sketching and scribbling, “Be sure to say this in the film,” “Don’t forget to include this,” and the recurring, “This is the truth.” It was as if he felt his approaching mortality—a perception that only fueled his obsession to set down as many memories as he could before the end.

Golod, who also produced the film, and co-producer Melanie Vi Levy have done us all a service by allowing us a glimpse at the artist and his unforgettable work.

As Kruger puts it, “I do not think I have ever seen anything in his work that was not literally shouting at me. It’s part of the mark of the artist. But it’s something more than that. It’s that kind of trait—the trait of standing up for your memories. Making certain that your memories are part of the collective memory of the world. I find that’s almost a moral lesson that I’ve learned from Nathan.”

Nathan Hilu was charged with shining a spotlight into the cells of Nazi criminals. By standing up for his memories, he allows us to see what he saw: Evil’s true face—small, recoiling from the light and with nowhere to hide.