-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

“Not in Our Town”—The Miracle of Magic City

Billings, Montana earned the nickname “Magic City” due to its explosive growth since its founding as a railroad town in 1881.

Magic City is the largest town in Montana. Though no rival in size to New York or L.A., nor even Raleigh, North Carolina, Billings nonetheless boasts some of the most beautiful tourist attractions in the U.S.—from Pompey’s Pillar to Pictograph Caves to Chief Plenty Coups State Park.

Billings is also home to a diverse and beautiful population, and it is they, the people of Magic City, who stood center stage that winter of 1995, the stars of a holiday miracle that continues to resonate today, nearly a quarter of a century later.

In 1995, Billings was home to 84,000 souls who lived, worked and played in their idyllic town largely outside the glare of the world’s spotlight. There was no inkling early that year, however, that the community was a key component in the neo-Nazi group, Aryan Nations’ plans to cleanse the Northwest five-state area of all Jews, people of color and “deviants.”

Aryan Nations, in alliance with the Ku Klux Klan and other hate groups, converged on Billings in the spring of 1995. First step: fear. Thousands of flyers distributed around town screamed, “Nuke Israel,” “Jews Out!” and other such slogans. Swastikas popped up on walls, park benches and other public places. A gay man was severely beaten, Native American children were harassed on their way to school and several African Americans received death threats.

That night, six more homes with menorahs, along with a Methodist church donning the same, were vandalized. But more menorahs appeared.

Sarah Anthony, the chair of the local Human Rights Coalition, called a town meeting. Resolutions and petitions decrying hate and bigotry were swiftly drafted and passed. Police Chief Wayne Inman urged that all such instances of hate and defacement be reported. County Sheriff Chuck Maxwell warned: “Don’t be silent… silence is acceptance.”

But the attacks only intensified. The leader of Aryan Nations had expressed the group’s strategy succinctly: “By whatever means we will purify this area. If we have to kill, we will do so.” They weren’t leaving Billings until their “program” was complete.

By the fall of that year, tombstones at a Jewish cemetery were overturned. Dawn Fast Horse, a Native-American woman, woke one morning to find her house covered in swastikas and obscenities. Uri Barnea, conductor of the Billings Symphony and himself the son of Holocaust survivors, sat down to dinner and heard the crash of a bottle thrown at his front door. Klan members invaded an African-American church service, standing at the back of the room, arms folded threateningly, before leaving mid the service. When the service ended, the congregation found the outside of their church defaced with racist graffiti.

Then, in early December, the miracle began. Five-year-old Isaac Schnitzer put a menorah up in his bedroom window to celebrate the Jewish festival of Chanukah. That day, a cinder block crashed through Isaac’s window and landed on his bed. Thankfully, he was at school at the time. But when Isaac’s mom, Tammy, herself a converted Jew, came home to find her son sobbing on his bed among shards of glass and the shattered menorah, she was moved to action.

She alerted the local paper, the Billings Gazette, and insisted the hate crime be featured on the front page. The Gazette’s editor obliged, but felt he could do more. He remembered a story he’d heard as a child about the Nazi occupation of Denmark—about how, in solidarity with the oppressed Jewish population of his country, the Danish king, Christian X, himself donned the yellow Star of David, and urged his countrymen to do the same.

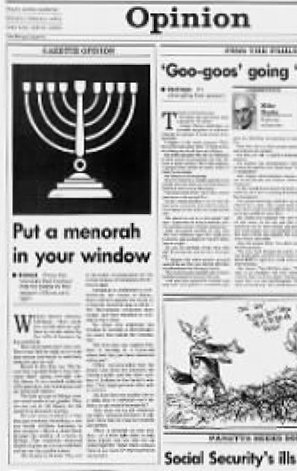

Inspired, the editor placed a full-page image of a Chanukah menorah in the next morning’s edition of the Gazette, and urged the families of Billings to cut and tape the printed menorahs to their windows. Within hours, thousands of Jewish, Gentile and Native American homes featured a menorah proudly displayed.

That night, six more homes with menorahs, along with a Methodist church donning the same, were vandalized. But more menorahs appeared. Local businesses, stores and churches printed and distributed them. Menorahs were everywhere: in houses, trailer parks, storefronts, and places of worship of all denominations. That Sunday morning, African-American church attendance was boosted by the attendance of Jews, Native Americans, and others of all faiths. Moreover, teams of volunteers painted out every vestige of hate on homes and public places that had been defaced.

“These are our neighbors. If a brick goes through your neighbor’s window, you’re there, right? What’s the big deal?”

And when the bell tolled at the end of the final church service early that Sunday evening, the congregation left the sanctuary into the twilight and found—nothing. The haters had left. Nothing more was heard from Aryan Nations, the KKK or any of their allied hate groups. Overwhelmed by the power of unity and love, they’d packed up their bigotry and slinked back under their respective rocks.

Meanwhile, what happened in Magic City did not go unnoticed. A documentary, Not In Our Town, chronicled the Chanukah miracle of Billings, Montana. Inspired by the miracle, a Not In Our Town Movement sprang into being throughout the land that— through partnerships with schools, communities and law enforcement—helps prevent bullying and intolerance, stops hate crimes and violence, and promotes safety and harmony for everyone.

The people who participated in the miracle of Billings are gratified but somewhat surprised at all the attention their actions spawned.

The painter whose company repainted Dawn Fast Horse’s house observed: “These are our neighbors. If a brick goes through your neighbor’s window, you’re there, right? What’s the big deal?”

And as one volunteer commented, “There’s an Iroquois word, which roughly means, ‘The benevolent desire of the soul.’ The idea is that all of us have that benevolent desire within us. You simply have to let that benevolent desire out.”