-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

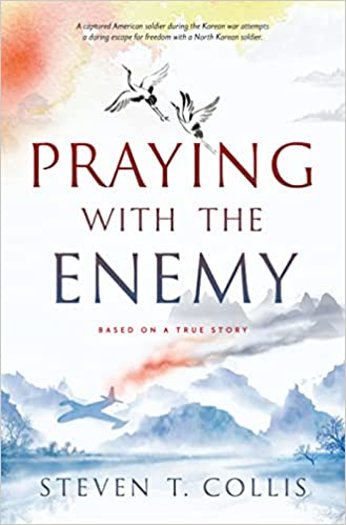

Praying With the Enemy: Steven Collis’ Eloquent Argument For Faith In Spite of All

University of Texas at Austin law professor Steven T. Collis has a passion for storytelling and religion and an interest in the Korean culture and its people.

One day more than two decades ago, in the basement of a university library, he found something that fed all three enthusiasms: an out-of-print memoir set in the Korean War about the friendship of a downed American pilot and his North Korean counterpart—two individuals who were technically enemies but bound together by a need to survive and, surprisingly, their faith.

Collis has taken that forgotten narrative and, with the help and encouragement of the two men’s surviving families, woven a novel (for that is what it is by the necessity of his art) that is compelling in execution and inspiring in its impact.

In Praying with the Enemy, an American pilot flying on a mission encounters a mechanical malfunction and finds himself hobbled in enemy territory with two broken ankles. He is soon captured and subjected to interrogation and abuse as a POW with little hope of escape. Weeks and months dragged on with no word, and despite gentle chiding from well-meaning friends and family to prepare for the worst, his wife Barbara never gives up hope that he will return home.

With their mutual religion as common ground, the two learn to communicate without language and ultimately help one another escape.

Kim Jae Pil is a young North Korean man drafted into a war he does not believe in.

But there is where any similarity to the standard-issue war story ends, for this is a story more about inner conflict and the toll war takes on the spirit than about the usual chronicle of bombs and bloodshed.

Though Collis allows us entry into the thoughts of all three of the main characters, it is Ward Millar, the downed pilot, with whom we spend the most time and through whose eyes we primarily experience events. Ward is an Everyman, feeling like so many of us the need to have faith, only to see it invalidated at every hand. Already embittered by the horrors of WWII, whatever faith he had has long since been out-shouted by logic—the truths of faith so easily dissolving in the light of reality.

Barbara, on the other hand, is a devout Catholic, her faith born of the conviction that there are things that so surpass logic that to pit the two against one another would be unthinkable.

So when Ward is reported MIA she, unlike her family, knows he is still alive.

Why?

How?

She just… knows, that’s all. If he were dead, she would know that, too.

Jae Pil, a Christian in a Christian family, has seen his religion’s observances, customs, beliefs and very identity outlawed by the new communist regime in North Korea. Separated from his family with his dream of building a church dashed (the land he set aside for it had since been appropriated by “The People”), he continually prays and plots a means to escape to the South where his family has fled. He is then suddenly and inexplicably thrust together with Ward, the “enemy.” Beginning with their shared religion as common ground, the two who are different in every other way learn to communicate without language and ultimately help one another escape.

Collis’ novel is a three-way love story: Ward and Barbara’s unshakeable resolve to be together again, the growing love and respect between former enemies Ward and Jae Pil, and, weaving through every chapter, the challenge that all three confront of loving God in the face of all practical sense, irrefutable reality and unspeakable odds.

Ward has made it clear to Barbara from the beginning that he cannot commit, as she has, to being a devout, observant, church-going Catholic. He has simply seen too much.

Early in the novel he knows he needs—or rather feels he should need—to pray, to put his faith in something greater than himself to help him escape, but he simply can’t. As Collis writes: “He pondered the workings of the universe in all its expansion and rotations and perfect mathematical circularity. All the days in his youth, dissecting the world with his brother, he had become certain that whatever force had constructed the vast eternity of it all would never take the time to tweak its many complex workings only for him. It would be like a major factory changing its schedule to help two fleas trapped inside a machine.”

When Ward prays at last, fervently and sincerely, out of a well of anguish from which he preposterously draws hope, we are there with him.

Jae Pil, for his part, sees escape scheme after escape scheme fail, despite prayers and faith: “He just didn’t understand it. Why would God have led him all the way to this place, so close to freedom, only to snatch back that blessing at the last possible moment? My God, My God, why hast thou forsaken me?”

Yet one thing the two men have to acknowledge separately, then together, is that they are ultimately sustained—Ward alive, Jae Pil’s escape plans undiscovered—by a force that defies logic and conventional wisdom.

We see the transformation not just through Ward’s thought process but in the imagery Collis uses as well. Early in the book, before Ward’s epiphany, the imagery and descriptions are straightforward, as one would find in any good, crisply written war story. But as Ward turns to faith, the images change, tending more toward the spiritual and religious: “Ward stared at the hill before him the way he imagined David must have stared at Goliath.” And: “Then, a quiet moment passed—a sacred second, he thought, because he felt her. Barbara.”

When Ward prays at last, fervently and sincerely, out of a well of anguish from which he preposterously draws hope, we are there with him: “In his mind, he recited the prayers, while simultaneously giving thanks—for the miracles that had kept him alive… for living another day when the time of so many was not extended. In those prayers, his mind went into a place beyond perception, drifting away from his body and broken bones to another plane of existence… There, in that place beyond knowledge, he talked with Barbara. In a quiet voice, or perhaps no voice at all. I’ve prayed, Barbara, he said. I’ve prayed. He wanted so badly for her to know that. Somehow, he knew the message would get to her. He didn’t know how, whether she would feel it or see it or hear it like a whisper carried by a soft breeze, but he knew it would reach her. When he returned and felt the earth beneath his aching body and a nighttime breeze blowing in directionless bursts just strong enough to reach him in the hole, his eyes were brimming with tears.”

It is with those words and others like them that Praying with the Enemy transcends the status of a good summer beach read and achieves a far higher purpose. For Steven Collis has drawn on his own convictions, and it shows. He has produced a heartfelt and earnest story to reassure the faithful and reawaken those who doubt in what is both a page-turning adventure yarn and an ode to the human spirit.

Collis’ resumé includes a juris doctor degree in law. As the faculty director of Texas’s Bech-Loughlin First Amendment Center and Law and Religion Clinic, he specializes in matters concerning that revered clause of the Bill of Rights.

But with Praying with the Enemy, Mr. Collis has made a far more persuasive argument for freedom of religion than any legal brief ever could have.