-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

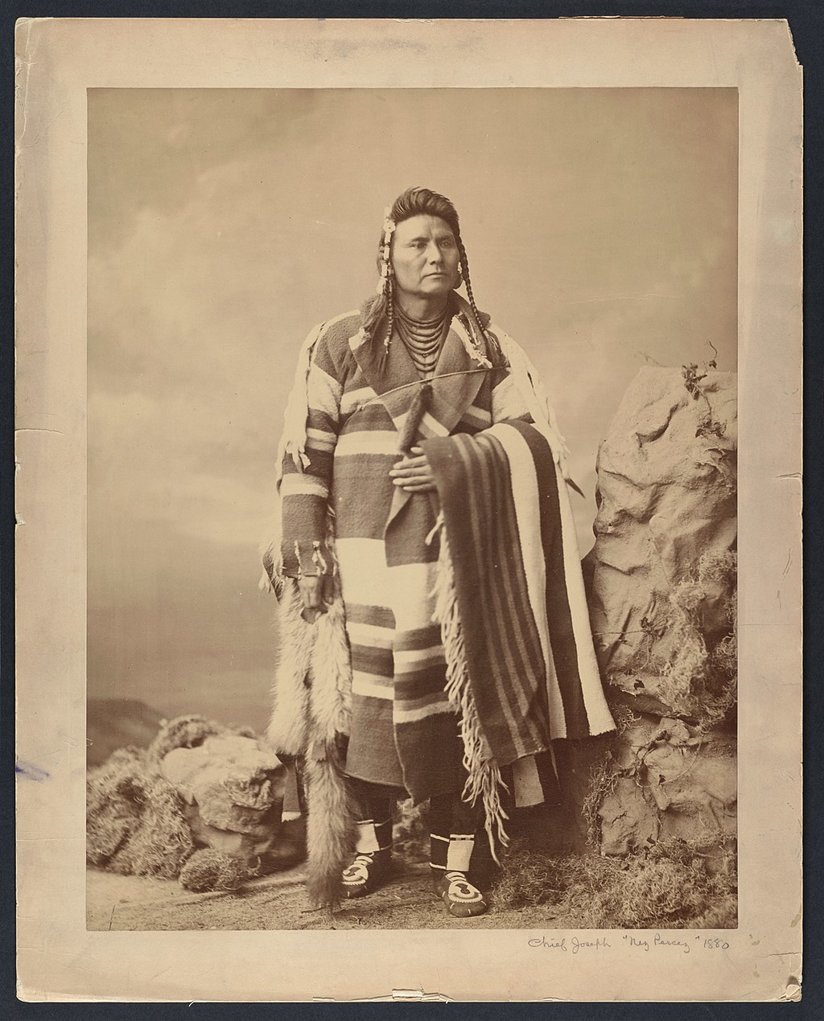

Remembering the Nez Perce and Celebrating Their Truth for National Native American Heritage Month

“Tell General Howard I know his heart… It is cold and we have no blankets. Our little children are freezing to death. I want time to look for my children and see how many of them I may find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs, I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”

– Chief Joseph, October 1877

Among the many stories to be remembered this National Native American Heritage Month is the journey of the Nez Perce.

Once a populous tribe of the interior Pacific Northwest, in the 1870s the Nez Perce were ordered by the U.S. Government to abandon their ancestral home in northeastern Oregon and move to a small reservation in the Idaho Territory. The Nez Perce, led by Chief Joseph, resisted. Several violent encounters with white settlers in the spring of 1877 compelled them to attempt to reach Canada for asylum alongside the Lakota.

The fighting retreat along 1,170 miles pitted 700 native men, women and children—hungry, ill-equipped and poorly armed—against the well-armed, well-fed and disciplined U.S. Army. Though the outcome was a foregone conclusion, the bravery and cunning of the Nez Perce and their chief in the face of incredible adversity earned them the widespread admiration of the world. The New York Times wrote in an 1877 editorial on the Nez Perce War that, “On our part, the war was in its origin and motive nothing short of a gigantic blunder and a crime.”

For decades thereafter until his death in 1904, Chief Joseph wrote, petitioned and spoke on behalf of fairness to his people and for a return to their native lands. Though well-received and well-respected, he was never accorded his wish, and the Nez Perce passed into history, icons of the Indian Wars—famous, admired, but a thing of a long-dead past.

Among the many stories to be remembered this National Native American Heritage Month is the journey of the Nez Perce.

The Nez Perce were once a proud and flourishing people whose numbers exceeded 6,000 when first encountering the Lewis and Clarke Expedition at the start of the 19th century—a people who once claimed 17 million acres spreading over what is now four states. Now confined to a plot of barren high desert less than one-tenth that size, it appeared the journey of the Nez Perce tribe was over, its territory and traditions now fodder for the profit of tour companies. Riverboat excursions today ply those curious enough to hear, for a fee, the story of the Nez Perce, the story as told by strangers whose ancestors pushed the Natives aside nearly a century and a half earlier simply for being in the way.

But then, in 2019, Stacia Morfin, an energetic full-blooded Nez Perce, took matters into her own hands. She founded her own riverboat company, Nez Perce Tourism, which features “Hear the Echoes of Our Ancestors” tours along the Snake River between Idaho and Washington.

Dressed in native costume—200-year-old buckskins with beads and feathers, her long hair separated into two braids kept in place with multicolored clasps—Morfin regales her customers with stories of her people who call themselves the Nimiipuu (“Nez Perce,” meaning “pierced nose,” was a name bestowed upon them by French-speaking fur traders) while her Uncle Maurice sits in the bow of the boat and beats a drum in time to her voice.

The Nez Perce were once a proud and flourishing people whose numbers exceeded 6,000—a people who once claimed 17 million acres spreading over what is now four states.

Morfin, whose name means “One Who Takes Care Of Water,” has a simple motive. “People are looking for a relationship with authentic people,” she explains, “and we’ve been here for centuries.”

Stacia Morfin’s indigenous tour of the Snake River continues the journey of the Nez Perce, a journey which seemed at an end a century and a half ago, but which, thanks to her efforts, has been given a new head of steam.

Theirs was a journey for fairness, justice and the chance to live in peace, their traditions and identity intact. Contact, communication and education, it turns out, are the keys to obliterating bigotry.

“We know there’s three sides to every story,” Morfin says. “The first side, the second side and the truth.

“We like to share the truth.”

This month, marking the deep and rich heritage of Native Americans, is the perfect time to share that truth.