RFI Panel Explores the Freedom of Religious Institutions

When you talk or write about “religious freedom,” you are understood to be referring to the First Amendment’s sacred right of individual conscience to believe in Whatever or Whoever one chooses to believe in, and to follow up that faith with whatever meaningful practice that involves.

There is, however, another key facet of religious freedom, and that is the freedom of a religious community to practice its faith without interference. Religion in the real world is, with almost zero exceptions, communal and institutional. One has needs—both spiritual and practical—that can only be provided by a group, and that group must be as free from state control as the individual.

It was with that fact in mind that the Religious Freedom Institute’s (RFI) Freedom of Religious Institutions in Society (FORIS) undertook and completed a three-year project to define and validate what precisely institutional religious freedom is and what it encompasses: not just houses of worship but religious organizations such as schools, hospitals, charities—in short, the full range of the uses of religion in both the spiritual and material world.

According to FORIS, its project focused on three questions: What is institutional religious freedom? How is institutional religious freedom faring globally? And why is institutional religious freedom worthy of public concern?

The completion of the project was marked last week by two virtual panels of leading religious scholars and experts who explored those three questions, and then some.

Religion in the real world is, with almost zero exceptions, communal and institutional. One has needs—both spiritual and practical—that can only be provided by a group.

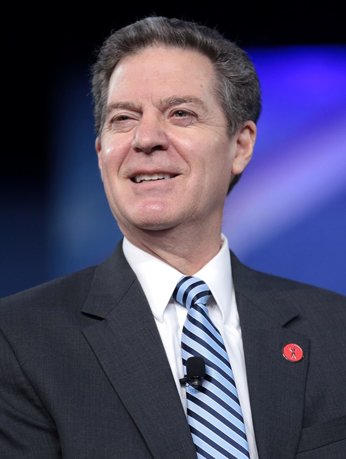

Keynote speaker and former Ambassador-at-Large for International Religious Freedom Sam Brownback, noting that the U.S. is “the mother ship of the right to religious freedom,” painted a dark picture of the future should that freedom not be consolidated and protected globally—not just for individuals but for religious institutions as well.

Mr. Brownback observed the axiomatic fact that, throughout history, genocide is preceded by persecution and marginalization of a religious minority. He pointed to China as “the leading enabler of religious persecution in the world” with its high-tech “smart” bigotry in the form of ID cameras and profiling, in addition to active concentration camps and repressive laws such as the banning of the name “Muhammad” for newborn Muslims.

Forecasting a “clash of civilizations” unless institutional religious freedom is made a priority foreign policy issue throughout the world, Mr. Brownback said, “We’ve got to stand up for this human right or there will be carnage… Time is short.”

The panels then tackled some of the thorny questions attendant to protecting religious institutions: how does one preserve a religious institution’s rights without occasionally trampling on the rights of another group that comes in conflict with that religion’s teachings? How does a government address a public health crisis, such as a pandemic, through restrictions on public church attendance without violating that congregation’s right to peacefully worship without outside interference? Should the religious freedom enjoyed by such “obvious” entities as private and parochial schools be extended as well to secular establishments with a religious “ethos,” such as Chick-fil-A (Christian) or Whole Foods (Buddhist)? Must a Catholic store owner accommodate a Seventh-day Adventist employee who has a different day of rest?

The panelists wrestling with these questions are themselves veterans of spiritual wars. Moderator Mark Rienzi, President & CEO of the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, represented the winning parties in a variety of Supreme Court religious freedom cases. Timothy Shah, Distinguished Research Scholar at the University of Dallas, was the architect of the FORIS project itself. His wife, writer and pioneering religious freedom investigator Rebecca Shah, was among the first to explore the impact of religion on the poorest and least industrialized nations. Paul Marshall, Wilson Professor of Religious Freedom at the Institute for Studies of Religion at Baylor University, has authored 20 books and over a hundred articles, most of them focusing on religious freedom.

Throughout history, genocide is preceded by persecution and marginalization of a religious minority.

They, along with the other distinguished panelists, Stanley Carlson-Thies, David Trimble, Kathleen Brady and Katherine Marshall comprised an all-star team of thought and action in the cause of institutional religious freedom, offering solutions ranging from constitutional to legislative to educational to political to social.

Mr. Trimble argued that religious freedom is a core component of our country as founded and so should never be put on the defensive, nor put in a position where “exceptions can be made.” Ms. Brady, while acknowledging that government is interested in protecting human life, spotlighted the claim by religious institutions that the government’s recent restrictions against public gatherings discriminated against them in favor of commercial and recreational sites. Ms. Marshall reflected on how the scope of the pandemic has affected the religious community’s ability to respond to the suffering and pain in its wake: the elderly, the disabled, women, the heartbreaking new factor of “COVID orphans, neglect of refugees, forced migration and the increase in domestic violence.” Mr. Carlson-Thies spoke about an upcoming bill in Congress, the Fairness for All Act, which he stated would amend civil rights protections for both religious institutions and LGBTQ communities representing a landmark win-win effort, as opposed to “us versus them.”

One takeaway from the panel is that there is a clear answer to the FORIS project’s third question: “Why is institutional religious freedom worthy of public concern?” The answer is that the continued health and independence of religious institutions is connected directly and inevitably to those things that keynote the common good in any society: a robust economy, a transparent governing body, a stable and peaceful social order, and continuing care for the needs of society’s people.

In 2015, the Church of Scientology’s Freedom Magazine posed the question: What would a day without religion look like? The answer? Not good. Millions would go hungry as the overwhelming percentage of agencies giving food to needy individuals and families are affiliated with religious institutions. Nearly half of the volunteerism and community service organizations would vanish. Higher education would be crippled, as nearly 20 percent of American colleges and universities bear a religious affiliation. Nearly one-fifth of our hospitals would shut down, creating a catastrophic healthcare crisis. Most of all, avenues for compassion for those at-risk and in need would no longer be there, representing billions of dollars for the millions of disenfranchised who would continue to suffer from famine, disease and dismay.

It would be a dark and soulless world without our religious institutions to coax us to care for each other and to believe in something greater than ourselves.

The Religious Freedom Institute’s distinguished panel has done its part to show us how to open the door to freedom for religious institutions, as well as individual freedom of religion.

It is up to us to walk through that door and widen the portal for others as well.