Sacrifice

As a child, I was determined to go to war. Not as a soldier, but as a photojournalist. The work of photographic correspondents like Don McCullin and Philip Jones Griffiths filled the pages of Sunday periodicals. Not only armed conflict, but natural disaster, the famines in Ethiopia and Africa, the acts of genocide in the Cambodian killing fields, seemed to become weekly fare. Some said that each new photograph of the suffering and deprivation desensitized us, and we became inured to the effect. For me, it was the opposite. With each new brutal and unforgiving image my desire to do something grew. I wanted to have a voice. I wanted to say I had done something— however small—to change the seemingly endless history of Man’s inhumanity to Man.

My aspirations changed as I grew up. I took a different direction, pursued a different career, but that sense of purposefulness never faltered. That wish to do something that would make a difference has remained, and—if anything—has grown stronger with each passing year.

Something else that has not changed, despite the passing of nearly 40 years, is the atrocities that are routinely perpetrated by human beings against their fellows.

In 2016, the worst drought in more than 50 years brought cataclysmic consequences to East Africa. More than 11 million people were uncertain where their next meal might come from, and another one and a half million were on the verge of famine. With this life-threatening reality facing them as an unchanging routine, desperation brought age-old fears to the surface.

Those fears, manifesting themselves in the most brutal and terrifying way, have served to confound and dismay, traumatise and perplex.

Autumn, 2016. In a town called Katabi, just 24 miles from the capital, Kampala, Ugandan police arrested 44 suspects in connection with a spate of killings of children and women. Uganda Police Inspector General Kale Kayihura said one suspect confessed to killing eight women.

Pastor Peter Sewakiryanga, who heads the Christian organisation Kyampisi Childcare Ministries, said children disappear in the country every week. These children are often later found dead. Those that are found alive have been subjected to horrific mutilations and amputations.

For here, in this troubled and turmoil-ridden nation, the practice of human sacrifice is as real today as it ever was.

Seven children and two adults were sacrificed in 2016, said Moses Binoga, a police officer who heads Uganda’s Anti-Human Sacrifice and Trafficking Task Force. Seven children and six adults were sacrificed in 2015. These are killings that are known to have taken place. Binoga estimates that the actual number of deaths is a great deal higher.

One of the perpetrators was Herbert Were, a 21-year-old resident of Busia town in Eastern Uganda. His crime: beheading his eight 8-old brother.

To quell the wrath of ancestral spirits, to encourage a successful harvest, and—certainly in the case of Herbert Were—to gain personal wealth, the practice of human sacrifice is undertaken.

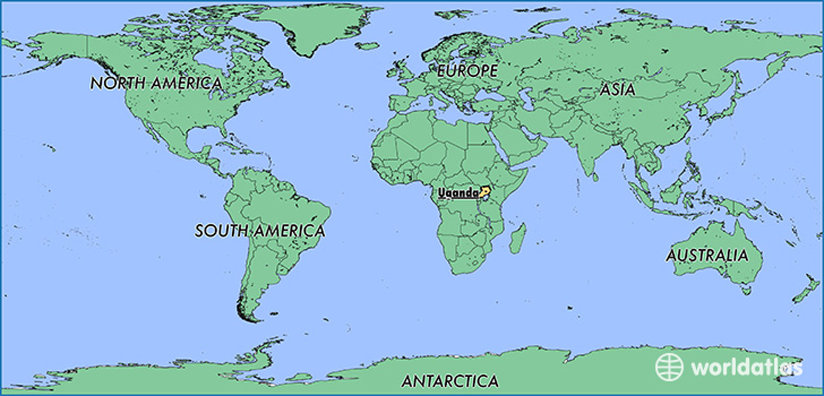

Uganda, an East African landlocked nation, bordered by Kenya, South Sudan, the Congo, Rwanda and Tanzania, possesses a national history marked by war and corruption. It is one of the countries that featured so predominantly in those Sunday periodical photographic articles from my youth.

Even now, more than 40 years after he was deposed from power, the legacy of Idi Amin—tyrannical Ugandan dictator—scars the nation’s psyche. Amin, who ruled with military support for eight years, is believed to have been responsible for the deaths of half a million Ugandans. His oppressive dictatorship is compared to the likes of Pol Pot, Nicolae Ceaușescu and Radovan Karadžić.

But Amin, despot though he was, played only a small part in denigrating a once-proud and fiercely nationalistic people. Quite aside from politics and war, a far more fundamental situation exists, itself perhaps a significant contributory factor to Uganda’s much-criticised human rights record and her history of internal political corruption, and that is the inescapable reality of poverty.

Though progress has been made in reducing poverty levels, with the percentage of those living below the national poverty line dropping from 31.1% in 2006 to 19.7% in 2013, it has to be acknowledged that when simple survival consumes the vast majority of a family’s mental and physical resources, the hope for advancement is limited in a way that few of us can even comprehend. When the barest necessities of existence are a daily battle, people can become truly desperate. And—as has been said in so many very different ways—desperate situations prompt desperate measures, even when those measures challenge the very nature of humanity.

Uganda is not alone in this. Other African states reported to engage in the same rituals and sacrificial practices include Tanzania, Nigeria, Swaziland, Liberia, Botswana, South Africa, Namibia and Zimbabwe.

Perhaps to you, to many of us, such a belief—that a child should be mutilated or murdered in order to guarantee a harvest or rid the village of an evil spirit—may seem like nothing more than the expression of grotesque and inhuman superstitions. But such sacrifices are based on a committed faith system that goes back many hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

So, if we are staunch supporters of the right to religion, freedom of speech, freedom of expression, and so many other elements that make up the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, then where does one draw the line?

If a Catholic has the right to be baptised and to insist that his fellows abide by the Ten Commandments, if a Buddhist believes that one is reborn time and again until Nirvana is achieved, if a Jehovah’s Witness can refuse to celebrate birthdays, Easter and Christmas, then why cannot a Ugandan witch doctor perform the ritual of sacrifice on a child to ensure that the harvest is bountiful?

Because such a sacrifice is murder, and murder of this nature is not only against the law of the land, it is also a violation of Articles 1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 28 and 30 of the Universal Declaration.

Religion, traditionally, is a celebration of the spiritual nature of Man. Religion, in so very many ways, is an acknowledgement of the existence of God, in whatever form that God may be perceived and understood. A common theme throughout religious texts and holy works is the belief that God created Man in his own image, that Man was granted life and existence through the will of God, and that human beings—no matter their creed, colour, nationality or faith—were equal in the eyes of the Creator. The notion that one man has a right to take the life of another man due to a difference in religious belief is something that has originated with Man, not with God.

I challenge anyone to show me where an accurate interpretation of any holy work or religious text states that the murder of another human being is justified for any reason. Murder is murder, no matter the provocation or motive. If a “belief system” suppresses Man, subdues him, victimises, punishes, tortures or harms him, then is such a belief founded in the traditional sense of religion and the acknowledgement of God? I do not think so.

Uganda is a member of the United Nations, a member state of UNESCO and the African Union. Citizens who believe their human rights have been violated can file complaints to the Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights. Uganda has made binding agreements to adhere to its commitments to human rights, and its police authorities have demonstrated their willingness to arrest and prosecute those who are involved in the practice of human sacrifice.

We live in a modern and liberal age. Human rights are enforced, protected and defended more than they ever have been. The internet has played a significant role in highlighting and disseminating human rights violations, and thus raising global awareness of issues that concern us all.

However, with poverty, lack of education, unemployment, disease, famine, political upheaval and war a matter of “everyday life” in so many parts of the world, it is vital that we face up to our responsibilities. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is not a luxury. Nor is it a matter of choosing which Articles we would like to apply. Nor is it a case of enforcing those with which we agree and being lax on those that we do not.

We are all human. That was not a choice. We all have human rights. That is not a choice either.

Bluntly stated, the sacrifice of any Article of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights has to be as disturbing to us as the sacrifice of a child.