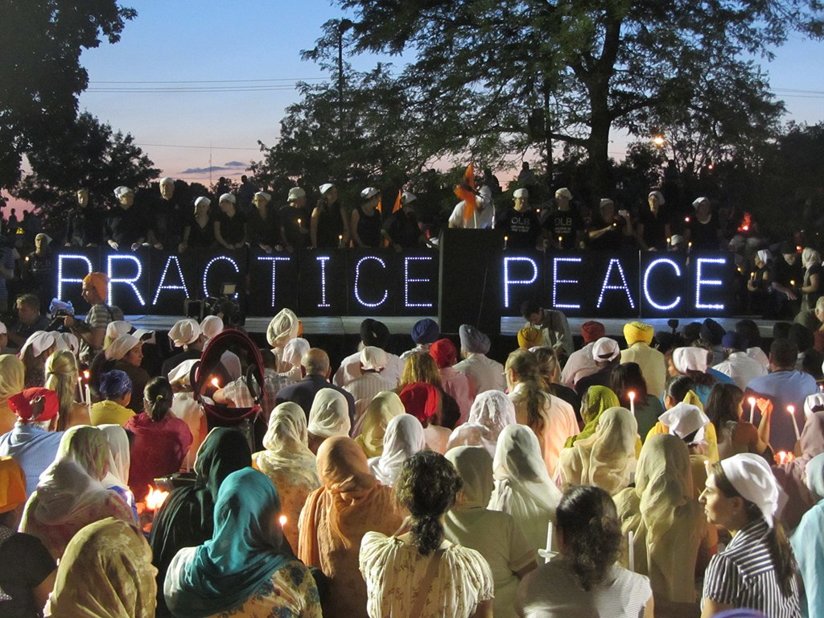

Sikh Coalition Marks 10th Anniversary of Oak Creek Shooting With Congressional Briefing

“And I alone have escaped to tell thee.”

– Job 1:15

The role of the survivor in bearing witness to tragedy and disaster is well known. He walks a path strewn with loss and regret. He endures the memory of horror and death as well as the pain of the loss of friends and loved ones.

He is a spiritual amputee—living evidence of the fruits of hate and evil.

In addition to enduring this soldered-in trauma and shock, the survivor of an attack on a house of worship or community bears the responsibility to tell his story, to teach others, and to serve as a constant reminder that this happened once and that to turn away means it will happen again and again.

Harpreet Singh Saini lost his mother to a hail of bullets that killed six others 10 years ago this month at Wisconsin’s Oak Creek Sikh Temple. The following night, he and his brother ate leftovers from the meal their mother had prepared the night before, realizing it would be the last time they would ever experience their mother’s cooking.

Three years later, Pastor Eric S. C. Manning, senior pastor of the historic Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, learned about the premeditated white supremacist attack on his church from his daughter, who saw the news on Facebook. Pastor Manning’s Church lost nine persons, including three fellow pastors. The killer had researched the church, its comings and goings, and knew there would be people there that night.

“I came here today to ask the government to give my mother the dignity of being a statistic.”

Rabbi Jeffrey Meyers at first thought the noise he heard outside the sanctuary that fall Sabbath in 2018 was a coatrack falling. What he heard was, in fact, the first shots that killed two brothers at the entrance to the Tree of Life Synagogue in the deadliest attack on the Jewish community on American soil. Rabbi Meyers managed to rush four congregants out to safety before the shooter entered the sanctuary. In all, 11 people died, including three Holocaust survivors, and seven others were injured. Since that day Rabbi Meyers has refused to utter the word “hate”—refuses to grant it the dignity of utterance, calling it instead the “H-word.”

These three survivors—Harpreet Singh Saini, Rabbi Meyers and Pastor Manning—appeared before a Congressional briefing in late July, sponsored by the Sikh Coalition. The members of Congress in attendance—those with the power to legislate against crimes of hate and do their best to prevent it—were Congresswoman Grace Meng of Queens, New York, a district with a large Sikh community; Senator Dick Durbin, chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee and author of the Domestic Terrorism Prevention Act of 2022; and Senator Gary Peters, chair of the Senate Committee on Homeland Security.

They had come to listen, learn and promise.

Saini, who first testified before Congress seven weeks after the murder of his mother, said at that time: “Senators, I came here today to ask the government to give my mother the dignity of being a statistic. The FBI does not track crimes against Sikhs. My mother and those shot that day will not even count on a federal form. We cannot solve a problem we refuse to recognize.”

Saini succeeded that day 10 years ago: the FBI now tracks crimes against Sikhs. But today, he said, the danger is still there, still growing. “I’m grateful but not enough has been done,” he said. “Hate crimes have only gone up. We now have security cameras and guards. At first the government was checking with us, but then, it’s as though they checked a box and moved on and we haven’t heard from them since.”

Pastor Manning agreed. “We have cameras, we have to buzz people in. It’s a completely different paradigm from what we were in before,” he said. “We thought that [what happened to us] would be the end, but then, two years later, the massacre at Tree of Life happened.”

“Why is this happening in America?” he asked.

Rabbi Meyers added: “It’s not going to stop here. We know there’ll be another one. Whatever happened to the concept of ‘sanctuary?’ Our sacred spaces are no longer sacred. That’s where our federal government needs to come in. Otherwise, the Declaration of Independence becomes wishful thinking. Though we’ve experienced so much love and support, that’s not enough—we need to worship in safety.”

Members of Congress spoke in their turn, after which Senator Peters delivered his video message: “Combating this growing threat is what our law enforcement body says is the most dangerous threat to us, domestic violence led by white supremacy. Misinformation, disinformation. The federal government needs to prioritize its resources and its data collection to combat domestic terrorism while also respecting civil rights.”

Senator Durbin reminded the panel: “After the Sikh massacre, I held a hearing and I’ll never forget [Harpreet Saini’s] courageous testimony.” He noted that the Senate just had another hearing of the same sort—this time after the Buffalo shooting. “Why is this happening in America?” he asked. He then acknowledged that there are no simple solutions for hate crime but that passage of the Domestic Terrorism Prevention Act would be a start. “There’s more work to do and as chairman of the Judiciary Committee I hope to help you,” he said.

As the first Asian-American elected to the House of Representatives from New York and a minority whose Sikh constituents have experienced hate and marginalization, Congresswoman Meng could empathize. “Hate or discrimination of one community can be used to target other communities. And you can’t talk about hate crime without talking about the importance of education,” she said. “Our experiences are just as American as everyone else’s.”

The Congresswoman voiced her belief that education on other faiths and cultures should be a part of every K-12 curriculum.

The importance of education as a long-term solution struck a chord with all. “Education is a big part of it,” Saini said. “People need to know who we are and how long we’ve been here. Education is the most important part.”

Pastor Manning expanded on those words. “Realistically there has to be an understanding through education that there’s more that unites us than divides us,” he said. “Everyone in this country is connected by our basic human dignity and rights. We are all equal in that. Any father would want to see their child grow. Any son who loses his mother is going to mourn. We all suffer, we all feel pain, we all hurt, and that brings us together. We need to reclaim our respect and honor—we are all a part of collective humanity. We must have the courage to stand up and say, ‘No, I’m not going to act that way. No, I’m not going to say that. We can embrace each other.’ As Dr. King said, ‘We may have come to this country on different boats but we are now in the same boat.’”

“It starts at the kitchen table.”

The Rabbi gave an analogy of silos, explaining that we remain in the silo of those like us, which of course prevents us from learning about others. Citing Pittsburgh native Fred Rogers of “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood,” Rabbi Meyers said: “He understood that the bridge between silos—between our neighbors—is children. Once you get to know your neighbors you discover we are all the same. We should have to do a course on getting to know your neighbor—not just different faiths, but different cultures so we can have more understanding of who we are. Education is critically important. Every house of worship should have a course in world religions so that you’ll know what it means to be, for example, a Sikh.

“But it starts at the kitchen table. In the home. Learn at an early age and you won’t need the ‘H’ word.”

The elimination of the “H” word is the ultimate goal. In Pastor Manning’s words, “We must continue to remind communities throughout this land that love is stronger than hate.”

And as Sikh Coalition Executive Director Anisha Singh said, “Our communities must not mourn in vain. Action must be taken.”

The survivors all agreed that education is the key component. In a shrinking world where what harms you also harms me, we are all truly neighbors. But more than that, though we may have suffered no physical injury nor emotional scarring, we must yet also count ourselves among the survivors—those who bear witness and who demand accountability and help—no less than those whose pleas and entreaties we have just heard.