-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

The Controversy at Maunakea—Why Science and Religion Need Each Other

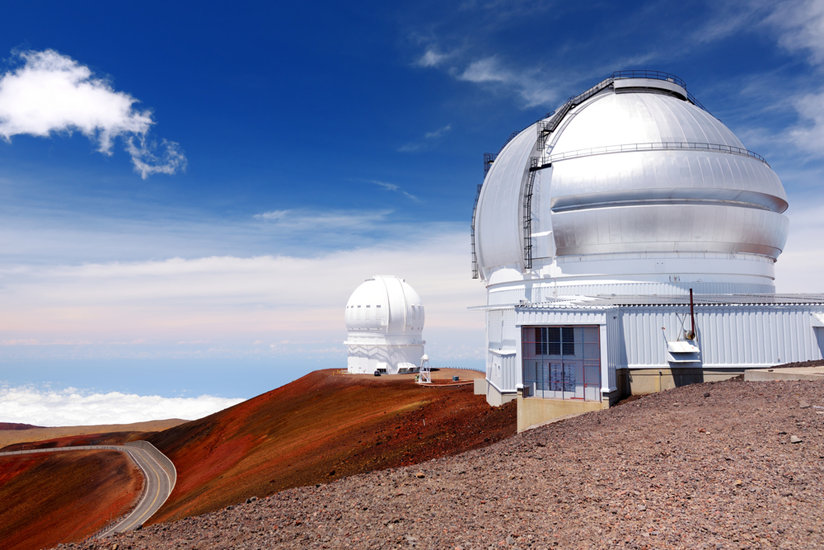

For the past several months a controversy has roiled Maunakea, a dormant volcano and the highest mountain on the island of Hawaii. The debate is over whether to build a 30-meter telescope which would be three times as wide and have nine times more area than any existing visible-light telescope on Earth. It would provide images 12 times sharper than those from the Hubble Space Telescope and give astronomers countless opportunities to better understand the universe.

According to the astronomers supporting the project, it “will allow us to see deeper into space and observe cosmic objects with unprecedented sensitivity. … When operational, [it] will provide new observational opportunities in essentially every field of astronomy and astrophysics.”

Maunakea has been chosen because its elevation combined with its relative isolation from interference make it an ideal observation platform, which is why there are already 13 telescopes on the mountain. However, the plan has also generated significant pushback from members of the Hawaiian Polynesian community, descendants of the original inhabitants who were there before the arrival of the English, Americans and others. They believe Maunakea to be the most sacred place in the Hawaiian Islands. One native Hawaiian, describing its place in their religion, stated, “Maunakea is considered an origin of Hawaiian cosmology, a Hawaiian equivalent to Christianity’s Garden of Eden. It is the meeting place of Earth Mother, Papahānaumoku, and Sky Father, Wākea. In turn, Maunakea is considered a piko, center, of the Hawaiian universe.”

The two quotes above summarize what have become opposing positions: one side believing that the spiritual and cultural concerns of the local population pale in comparison to the quest for scientific knowledge of the heavens, and the other fighting for its heritage, spiritual beliefs and practices. Imagine the reaction in France if, rather than restoring Notre Dame Cathedral, the French government proposed replacing it with a scientific laboratory, and you might understand the attitudes of the native Hawaiians who have been holding protests at the construction site and have, so far, successfully prevented the project from getting underway. For their part, some scientists have compared their plight to that of Galileo in the 16th century, who was prohibited by the religious authorities of his day from disseminating his discoveries and doing further observation of the heavens.

Yet science and technology, when divorced from spiritual values and respect for the many different cultures which comprise the human race, have given us the constant threat of nuclear warfare, the technological means to carry out atrocities such as the Holocaust, and many actual and looming environmental catastrophes.

The native Hawaiians deny that they are against science (Hawaiians take pride in pointing out that Hawaii’s royal palace had electricity and telephones before the White House did); they simply want to protect a sacred part of their legacy. They have also expressed concerns about the environmental impact of the telescope, including its effect on animal habitat and possible damage to an aquifer which supplies much of the big island with water. There are also unresolved grievances over denial of rights to land (which includes Maunakea) promised to Hawaii’s original inhabitants as part of the takeover of the islands by the United States at the end of the 19th century.

Legally, the battle is over. The Hawaiian Supreme Court rejected the last judicial challenge to the project in November 2018 and construction was supposed to start in July, which is when the current round of protests began.

But rather than using its advantage to force out the occupiers, the Hawaiian government has been trying to negotiate a resolution that somehow works for everybody. The proposed location of the telescope has been changed to a slightly less prominent position and they have suggested other concessions that might make the telescope palatable to those protesting.

There isn’t a question of either position being “right.” The human race needs science; it is very obvious that the expansion of scientific knowledge of the material universe has provided us with many benefits. Yet science and technology, when divorced from spiritual values and respect for the many different cultures which comprise the human race, have given us the constant threat of nuclear warfare, the technological means to carry out atrocities such as the Holocaust, and many actual and looming environmental catastrophes. So there may not be a question, but the answer is to support science and religion in their respective spheres.

Fortunately, there are a lot of people involved who do see the importance of both. For example, over a thousand members of the scientific community signed a letter calling for cooperation and honoring the values of the Hawaiian community.

Two native Hawaiian astronomers testified in favor of the project while it was moving through the courts. One of the arguments of pro-telescope Hawaiians is that their Polynesian ancestors had to observe and understand the movements of the stars in order to navigate the vast reaches of the Pacific.

A recent survey showed that 64 percent of the state population as a whole support the telescope. Among native Hawaiians, it is slightly less than half.

Hopefully, those involved will find a way to come together. If the supporters of science and those of Hawaii’s long-established spiritual and cultural values can find a solution that allows them to coexist and complement each other, it will have lasting value, and Maunakea will have become a symbol of hope and a bright future—not just for the people of Hawaii but for all of us on planet Earth.