-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

The European Court of Justice Strengthens the Right to Practice Bigotry

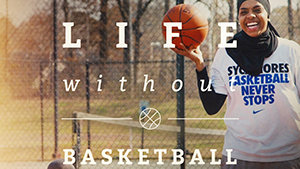

Head coverings have been a key part of the world’s three major monotheistic religions. The bride’s veil, the nun’s wimple, the Orthodox Jew’s yarmulke, the Muslim woman’s hijab may represent, in their own way, respect for the creator or devotion to one’s husband, or a modesty rooted in the downplaying of one’s physical appearance in favor of a focus on one’s spiritual nature. Sikhs view the dastār (a type of turban) as an emblem of spirituality, courage, and respect, and Amish women cover their heads with white bonnets, based on a passage in the New Testament.

Devotion, piety, respect, spirituality, courage. Who could possibly have anything against these? Apparently, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) does. It ruled on July 15, 2021 that employers can ban their staff from wearing religious symbols, including headscarves, in their workplaces. The ECJ, the highest judicial authority in the EU, ruled in two separate German cases against Muslim workers who were told their jobs were in jeopardy unless they ceased wearing headscarves.

Devotion, piety, respect, spirituality, courage. Who could possibly have anything against these?

Neither the continent of Europe nor its highest court has a reputation for religious tolerance. Witness the centuries of persecution wrought by the former and the recent ruling by the latter, as well as a ruling in 2017 that companies could ban staff from wearing headscarves and other visible religious symbols under certain conditions. The ECJ added fuel to the fire by stipulating that employers needed to show a “genuine need” for the ban, such as the “legitimate wishes” of the customer, including presenting a “neutral image towards customers or to prevent social disputes.” In other words, if your customer is offended by a worker’s religious beliefs, or if you as employer merely think that someone may be offended, your worker has no right to display his or her faith, but you have every right to display your bigotry.

Expressions of outrage to the July ruling were swift. The European Network Against Racism said that the latest ruling would “lead to justifying the exclusion of Muslim women, who are increasingly portrayed as dangerous for Europe, in the collective narrative.”

Speaking personally, I spent the greater part of over a dozen years of my life wearing a yarmulke. I wore it every day. I wore it in Hebrew school, at prayer, and at play. I wore it while studying Talmud and I wore it playing ping pong and Monopoly. I wore it eating and sleeping. And so did my friends. It was simply part of life, a reminder if you will, that, no matter what, there was Someone or Something bigger and more important than whatever mundane thing I was involved in. There was comfort in that knowledge, a perspective that one is not alone, that one is not a meaningless cipher in the Grand Scheme of it all.

If there was any resentment or offense elicited by my head covering, I was not aware of it. One day on the bus a woman sat down next to me and said, not unkindly, “So, honey, why do you people all wear those funny little beanies?” I told her the first thing that came to my mind: “I’m not sure, but it’s part of who I am and I feel better this way.”

To say that a person’s faith is very personal and important is to state the obvious. To observe, however, that what a person believes is part of that person, and as often as not defines that person, takes empathy and a wish to understand people as individuals, rather than as a demographic mass. The European Court of Justice, in failing to take these qualities into account, has fallen short of the character test—and that is a sin, no matter what faith you subscribe to.