The Fingerprint of the Spirit

I used to be comfortable with the theory of evolution, but my thinking has evolved.

The theory of evolution postulates that the many different forms of life all descended from a common ancestor, with the many and diverse genetic detours caused by natural selection, mutation, and other factors. Those mutations and variations in organisms occur randomly over time, with those variations which provide a survival advantage favoring a greater reproductive potential, ensuring the viability of that particular strain of mutation.

Evolution of a sort obviously occurs. If you visit Mount Vernon (George Washington’s home) perhaps the first thing you’ll notice is that doorways are lower to accommodate shorter people. In a mere few hundred years, mankind has “evolved” to where now, finally, we can play basketball.

But what of “real” evolution?

Given the staggering number of life forms, and the vastness of time, anything is (theoretically) possible. Extend the math, and presumably a fruit fly could one day evolve into a buffalo. It is a bit like the argument that if a million monkeys sat down at a million typewriters for a million years, one of them would one day write Romeo and Juliet.

The problem I have with this theory is that there is always a gap between the genesis of a mutation and that mutation developing into a tangible survival advantage. What motivates continued mutation until the creature crosses that gap and achieves a greater survival potential? New forms of life evolve over millions of years.

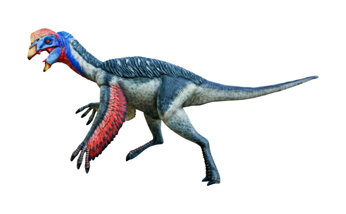

Take for example a bird. In order for a Theropod (the presumed ancestor of birds) to take full advantage of its evolutionary blessing—flight—it had to:

1. Grow its forelimbs into wings (wings of an appropriate size, and with an aerodynamic shape, and capable of being controlled).

2. Lose size and weight.

3. Develop lighter, air-filled bones (referred to as “pneumatized” bones).

4. Grow effective feathers (feathers perform many functions, such as steering, water repellency, insulation, aerodynamics, and possibly more, although as with the bat, perhaps feathers are not absolutely necessary to flight).

5. Grow an effective tail.

Within each of these major developments lie many sub-developmental steps: the bird-to-be’s “hand” had to lose its fifth and fourth digits, while the wrist bones underlying the first and second digits had to consolidate and take on a semicircular form that allowed the “hand” to rotate sideways against the forearm. This eventually allowed birds’ wing joints to move in a way that created thrust for flight. This is just one of the sub-evolutionary steps that had to occur for an effective wing to develop.

THAT these mutations occurred is evident. WHY they developed is where I have a problem.

An initial mutation creating marginally (presumably) lighter bones would have to be perpetuated and augmented down through subsequent generations of progressively lighter-boned animals before sufficient “pneumatization” to permit flight would have occurred. As Darwin stated, “…Natural selection acts only by taking advantage of slight successive variations; she can never take a great and sudden leap, but must advance by short and sure, though slow steps.”

What motivates that process to continue in each succeeding generation? There is likely no survival advantage in marginally lighter bones. In fact, without the other features of a bird, fully pneumatized bones may provide no survival benefit at all, and may possibly even be a detriment. Why would our initial mutant Theropod’s progeny continue in that direction? Genetic variation, as postulated by the theory of evolution, is a random activity until survival potential (plus or minus) takes a hand.

From the viewpoint of millions of years, evolution seems plausible. Getting there, however, is a concatenation of millions of generations, each linked one to the other by genetics. Break one link, and the chain fails.

But let’s assume that, unlikely as it seems, the vast number of Theropods available and the millions of years in which they lived provided enough opportunity for just such a series of events to occur.

Somewhere, then, we would have had a population of increasingly light-boned dinosaurs. Some of them would have to simultaneously mutate in the direction of growing their forelimbs, modifying their bone structure, and developing an aerodynamic shape—wings.

Just as with pneumatization, this is a process that would likely have no evolutionary benefit in its incomplete stages. Something would have to motivate continued mutation down through subsequent generations to eventually achieve wingdom.

Aha, but then what of feathers? Somewhere, a sub-subgroup of pneumatized and winged mutants would have to be developing feathers. Another sub-sub-subgroup of pneumatized, winged and feathered beasts would be developing a tail. Another is losing size and weight.

None of these changes fosters an increase in survival potential in an incomplete stage, or even in a completed stage without the other mutations (with the possible exception of feathers which do provide a stand-alone insulation benefit).

So what are the odds of our original strain of Theropods coordinating all of these different evolutionary dynamics down through millions of generations in order to arrive, 80 million years later, at a creature with a true survival potential increase—a bird?

Better minds than I could maybe do the math. I don’t need to. Common sense rebels.

Indeed, the systems I’ve described above have a scientific name—“irreducibly complex systems.” Organs such as the eye, the heart, and the ear, as well as numerous cellular level biochemical reactions, are recognized by scientists as being unable to function at all in any kind of partial evolutionary phase.

Even Darwin agreed. “To suppose that the eye with all its inimitable contrivances for adjusting the focus to different distances, for admitting different amounts of light, and for the correction of spherical and chromatic aberration, could have been formed by natural selection, seems, I freely confess, absurd in the highest degree.”

Let’s take another, different, whack at the evolutionary piñata.

Where’s the evidence of evolution today? Imagine our poor little Theropod, halfway there. His front limbs are longer and have begun to spread. Some rudimentary form of feathers adorn his body. He has gotten smaller, lighter. Perhaps his tail has begun to shorten and fan out. A scientist of the day, coming across one of these ungainly freaks (actually he would have to come across a community of these bozos if they were to have any hope of survival), would probably post a picture on his facebook page with a snide caption and a series of smirking emoticons.

In other words, why don’t we see a monkey, somewhere, typing out “O Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?”

So shouldn’t there be such mutants extant today? Evolution, as an expression of natural law, must be charging along today with the same fervor as it has throughout life’s term here on Earth. Shouldn’t our world abound with evidence of evolutionary detours in progress?

Why do we not have a herd of rabbits somewhere who have begun to lose weight, develop longer and fuller forelimbs, rudimentary feathers, etc.? Or a duck that is developing fangs and a whip-like tail? The odds are the same today as they were 200 million years ago when the Theropod-to-bird process allegedly began.

In other words, why don’t we see a monkey, somewhere, typing out “O Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?”

I retreat to common sense. The math CANNOT add up. Somewhere, there must be a guiding hand.

In Christendom, this guiding hand is called “Intelligent Design.”

Regardless of what term you use, if you accept the concept that there is more than random motion in play here, you immediately and necessarily open the door to religion. Here, in “evolution,” we have the fingerprint of the spirit on the physical universe.

Whose intelligence? Whose guiding hand? Whose design?

That’s the question every religion seeks to answer—Buddhist, Hindu, Christian, Muslim, Jew, Scientologist. I would add that once you open that door, every faith has a right to walk through it.

Evolution, rather than being the shoehorn that physical scientists use to cram complex observable phenomena into the physical universe shoe, is most simply and elegantly answered by admitting of a divine spark. The next step in our evolution will come when we can acknowledge and respect each of the many and various ways Man has devised to understand that spark.