The High Tech of Hate

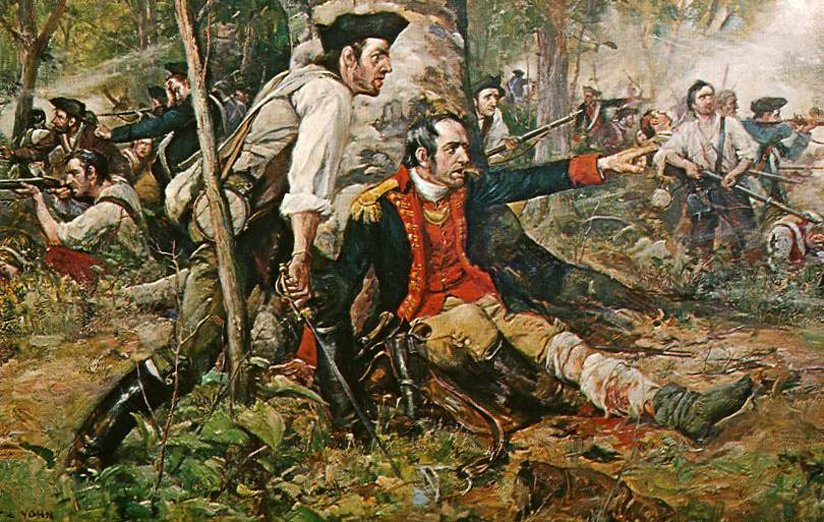

1777 began badly for the Continental armies led by General George Washington. Barely two months earlier, Fort Washington had been captured by the British, and the Americans shortly thereafter beat a hasty evacuation from Fort Lee, leaving supplies, food, cannon and ammunition for the taking by the delighted redcoats.

General Washington was disconsolate. He wrote several letters home, to his cousin Lund Washington, charged with overseeing Mount Vernon, and to his wife, Martha. In one, he confides: “But we have overshot our mark. We have grasped at things beyond our reach: it is impossible we should succeed; and, I cannot with truth, say that I am sorry for it; because I am far from being sure that we deserve to succeed.”

In the same packet of letters, intercepted by the British, Washington eloquently describes the unjustness of the war, yearns for reconciliation with England and asserts I love my King.

Or does he??

The letters were fake, clever forgeries concocted by a Loyalist who had studied GW’s writing style, and with an adroit blend of truth and fiction, lent them just the right air of authenticity to create trouble for the Father of Our Country when they were published and republished in dozens of periodicals on both sides of the Atlantic.

After decades of refusing to acknowledge the canards, Washington himself, at the end of his second term as president, finally issued a categorical refutation of the letters and put an end to the unpleasantness.

Lies and forgeries that forward agendas ranging from dislike to hatred of, to an urge to destroy individuals and groups, have always been with us. As technology advances, so too does the sophistication and expertness with which they are executed. As the means of communication improve, it brings out the best and the worst of us.

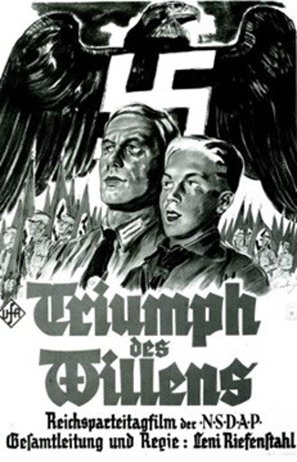

Witness Hitler’s PR machine which set the gold standard for the manufacturing of new “truth.” One of my most chilling moments as a teenager happened when my history teacher, Mrs. Eiss, screened, without introduction or preamble, Leni Riefenstahl’s brilliantly evil Nazi propaganda film, Triumph of The Will.

Sitting there in the darkened auditorium, bombarded with images of a powerful, all-benevolent Nazi party led by superhuman titan Adolph Hitler battling the dark forces of democracy and the Depression, one side of my brain shouted, “This is soooo bogus! You know what happened! You know what evil this man wreaked on the world!” while the other side, hypnotized, was “Wow, what greatness! What a man!”

When the lights came back on, Mrs. Eiss said, “Remember this: when you’re dealing with hate and prejudice, you’re dealing with people who don’t care about facts, truth or credibility. You’re dealing with a whole manufactured reality that cares only for power.”

In our own time, Mrs. Eiss’ words were only too prescient. There is no assault on true reality coming from white supremacists, neo-Nazis, anti-religionists, Islamophobes and their apologists and enablers. It is, rather, a battle for reality—the “right” reality, the carefully created and promoted reality.

So what is “reality,” anyway? L. Ron Hubbard tells us in his book, Scientology: The Fundamentals of Thought, “Reality is fundamentally agreement.”

What drives fact-checkers around the bend is that, no matter how much they work to dispel rumors, false data, lies and propaganda, the disseminators of such continue to repeat the lies, and their true believers continue to believe them. The fact-checkers don’t realize that it’s not a matter of credibility—the liars and haters don’t care about that—but, as my history teacher said, it’s a matter of power, and the ability to say whatever they want and have it be believed.

“When you amplify everything, you hear nothing.”

To compound the felony, the falsehoods are given further “credence” because they’ve now entered “the conversation” as those who try to discredit them only give them more airtime. What was once a situation of bald-faced lie versus proven, factual truth is now simply two dueling “points of view,” or, as one lawyer currently in the news put it, “Truth isn’t truth.”

The result is more noise and confusion. As humorist Jon Stewart once observed, “When you amplify everything, you hear nothing.”

A new term you’ll be hearing more in the coming months is “firehosing.” It means the telling and retelling of obvious lies at such a high and rapid-fire rate that their very ubiquity bypasses the need for credibility and creates a new reality.

Firehosing is characterized by four factors:

- High volume

- Repetition

- Shamelessness (i.e. zero commitment to objective reality) and

- No commitment to consistency (i.e., you can say one lie one day, then contradict it with another lie the next day, and do both with equal fervor).

Nazis, both then and now, use firehosing, as do haters and bigots and others who want to create an alternate reality that fits in with their own world view.

d79abaf4-076bBut a new factor has entered and has made its presence felt throughout all social and news platforms: video.

For years, video has been the ultimate argument settler and arbiter. If you catch someone on video saying something he claims he never said—if footage emerges that appears to show your point—then that’s it. End of story. You are right. You win. Media, both mainstream and otherwise, know this very well. Hyperlinks to video can support a point of view or bash an opponent. And video can now be used, with emerging technology, to almost flawlessly promote falsehoods and convert black to white and yes to no.

Thomas Kent, president and chief executive of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, calls this new phenomenon “Deep Fake Video.” Kent says that, as the technology advances, words can be put into people’s mouths, images altered, facts refuted and lies given credence. All with the awesome authority of video. It is, after all, the evidence of one’s own eyes. And if you can’t believe that, what can you believe?

A recent video of a Nobel Peace Prize-winning statesman opens with the man mouthing the most absurd and hateful anti-Muslim garbage imaginable, and to a wildly cheering crowd, at that. Your mind twists itself into knots. You thought this man to be a decent, loving, inspiring individual. But here he is, a shameless rotten excuse for a human being. How could anyone think otherwise?

Suddenly the video goes to split-screen. The Nobel Prize winner on the right, continuing to spew hatred; but now on the left is another person, doing a perfect imitation of the statesman, mouthing those very same hateful things, perfectly in sync with the speaker’s lip and mouth movements. Without seeing “the man behind the curtain” on the left, there is no way to tell that the speaker isn’t really saying those things.

The video was posted as a warning that you can no longer believe what you see on a video—the technology is that good. As Kent warns, “Society now has to learn that video no longer guarantees reliability. Instead, it could be the biggest lie of all.”

Someone I know posted a heartless anti-Muslim quote meme on Facebook. I answered (nicely) that it was a meme, had no attribution, and encouraged her not to use it. She answered my comment with two videos from a right-wing quasi-nationalist website with sensational rants about Muslim immigrants roaming the streets of Europe, raping innocent women and children, and warning that now they’re all coming here to do the same. The rants were punctuated by (unattributed) shots of thugs stalking innocent white people, and hazy video of someone attacking a woman. My acquaintance obviously felt that this video proved her argument and justified her hate meme.

No one is immune to video. This year a major world leader retweeted videos about alleged Islamist violence. One claimed to show a “Muslim migrant” beating up a “Dutch boy on crutches,” and another showed Muslim men pushing a boy off a building somewhere in Europe.

The videos were fake. The perpetrator in the video about the Dutch boy was neither Muslim nor migrant. The video of the boy being pushed off a rooftop had taken place in Egypt, not Europe, nearly four years earlier, during a spasm of violence following the ouster of then-Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi. The source of the videos was a British hate group.

But because a world leader had retweeted them, the videos soared in credibility and lent fodder to bigoted, anti-Muslim rant.

But there is something more sinister at work here. TV and video are hypnotic. The mind can absorb 20 images per second. Video runs at about 25 images per second. That means that for every second of TV or YouTube or any video, good or bad, well-intended or not, 5 images get implanted without our knowledge or consent. We sit like zombies, absorbing (and believing) what we see. We are hypnotized. More bluntly, we’re made stupid.

Stupidity is no way to live and no way to get along with others. Understanding goes down as stupidity goes up.

Would a worldwide moratorium on all video result in an overall surge in health, happiness, intelligence and understanding among the people in the world? Would tolerance flourish and understanding bloom, would bigotry, mistrust and irrational hate wither if we all stopped enforcing our realities on others and instead chose to share them with one another?

Would all the technology that we possess, enough to span the world in a nanosecond and conquer space and time, all fade to insignificance at the outstretched hand of a stranger reaching for ours in friendship, strangers no more?

Well, there’s only one way to find out.