“To Bigotry No Sanction, to Persecution No Assistance”—George Washington Defined America at Its Best

George Washington was displeased. The president of the brand new United States had determined to tour the former 13 colonies—now states—but one state was still withholding its approval of the Constitution. Rhode Island, nicknamed “Rogue Island” for its history of not always keeping on the dotted line of conformity, was still not satisfied that it, as the smallest state, would be protected by an over-powerful central government, and not bullied by the larger states.

The president showed his disapproval by snubbing Rhode Island on his tour. Chastened, the state’s legislature approved the Constitution in May 1790 and sent a representative to Congress three months later.

Ironically, the last state to say yes to constitutional government had been the first colony to introduce the radical concept of religious tolerance and inclusion a century and a half earlier. Rhode Island’s founder, Roger Williams, opened the land as a haven for those seeking what he called “liberty of conscience”—a concept better known in the ensuing ages as “religious freedom.” He established the first Baptist church in America, making those who had been persecuted for practicing that faith welcome. Soon after the Baptists, other persecuted minorities—the Quakers and the Jews for example—found sanctuary in Rhode Island, boldly building their houses of worship close to Newport’s town square and its seat of colonial government.

The Masons, the Catholics, the Quakers, the Jews all asked, respectfully but directly: Are we safe?

Washington was aware of Rhode Island’s open-door policy to any religious group. He was also aware of the importance of freedom of religion to the people of the state and its position at the very top of the Bill of Rights.

We can’t know Mr. Washington’s exact feelings about Rhode Island—we have no video interviews of him, no off-the-record remarks, no blog by his best friends. But thanks to a masterful video created by the Loeb Institute for Religious Freedom, To Bigotry No Sanction, Mr. Washington’s actions speak to us from across the ages, and speak loudly. On learning of Rhode Island’s ratification of the Constitution, he arranged a special visit, bringing along his Secretary of State, Thomas Jefferson, and an entourage of dignitaries to that state.

As was the custom of the time, the good citizens turned out to greet him, each group bearing a letter. The Masons, the Catholics, the Quakers, the Jews all asked, respectfully but directly: Are we safe? Will this government live up to the ideals set forth in the new Constitution’s Bill of Rights?

Meryle Cawley, Director of the Touro Synagogue Foundation in Newport, Rhode Island, the oldest synagogue in America, reminds us: “This is the first time in history that a government put into their constitution the right to be able to pray freely. It wasn’t perfect. A lot of other people didn’t have the same rights. If you were a woman, if you were from Africa or African American, and other ethnicities, you did not have these same rights. But this was the beginning of a time when people could come and know that they could pray freely without persecution.”

So the minority religions of Rhode Island needed to know: Was this just lip service or was this real? George Washington was the most admired man in the country, the hero of the revolution and, to many here and abroad, the face of the new nation. One word from him, one doubtful shake of the head, one raised eyebrow at the thought of a free haven for all religions would be all that would be needed to close the door on freedom of conscience forever.

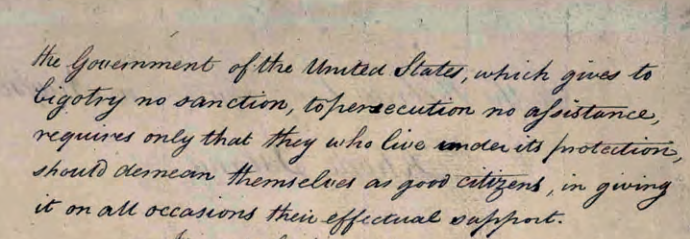

That is not what happened. The president wrote reassuring letters to each faith, guaranteeing them all an equal seat at the table. But to the Jews of Newport he gave more than the guarantee of safety. In 340 words he made his position clear, writing, “It is now no more that toleration is spoken of, as if it was by the indulgence of one class of people that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights.”

Ms. Cawley believes that passage is the crux of the letter. “What is he saying?” Ms. Cawley asks. “He’s saying: One ideal is toleration, but toleration is fleeting. I can tolerate you today and not tolerate you tomorrow. But if I say to you that it is your inherent natural right to have freedom to pray as you see fit, that goes beyond toleration to equality.”

“Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports.”

George Washington’s letter to the Jews of Newport, Rhode Island, was lost for generations in private collections. In recent years it resurfaced and can be seen at the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia. Visitors can read in Washington’s own hand, the phrase that sums up, far better than volumes of eloquent oratory or scholarly dissertation can, what we are at our best—what America is at its best: “Happily the government of the United States … gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance.”

Washington closed his letter with Old Testament imagery recognizable to any Jew: “May the children of the Stock of Abraham, who dwell in this land, continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other Inhabitants; while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and figtree, and there shall be none to make him afraid. May the father of all mercies scatter light and not darkness in our paths, and make us all in our several vocations useful here, and in his own due time and way everlastingly happy.”

Of Washington’s letter to the Jews of Newport, Rhode Island, Charles Watson, Jr., Director of Education of the Baptist Joint Coalition for Religious Liberty comments, “This story is more than just a Jewish story in America. It’s everybody’s story in America. It was then and it is now. So it’s important for that story to be told. It’s important for that story to be known because this is the bedrock of who we are.”

According to Dr. Jonathan Sarna, Professor of American Jewish History at Brandeis University, the idea that people of different religious beliefs should be treated as if they have an inherent natural right to hold those beliefs is, “as radical and as important today as it was when George Washington articulated it. That lesson, which is not an intuitive one and which has historically distinguished the U.S. from most other countries in the world, is a lesson that needs to be repeated for each new generation.”

George Washington understood, possibly more than most, that the idea that people have an inherent natural right to their religious beliefs is not, as Dr. Sarna pointed out, an intuitive one. And it is with that in mind that Washington devoted a passage to it in his farewell address. His final warning echoes to us across the centuries: “Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports. In vain would that man claim the tribute of patriotism who should labor to subvert these great pillars of human happiness, these firmest props of the duties of men and citizens.”

It is a warning we must heed. Our survival depends upon it.