-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

To Kill A Mockingbird Marks Anniversary

Atticus had used every tool available to free men to save Tom Robinson, but in the secret courts of men’s hearts Atticus had no case. Tom was a dead man the minute Mayella Ewell opened her mouth and screamed.

— To Kill A Mockingbird, Harper Lee

Sixty-one years ago this month, Harper Lee gave us a glimpse inside the secret courts of men’s hearts with the publication of her novel To Kill A Mockingbird. The world has not been quite the same since.

Drawing on scenes and stories from her own childhood in a small Alabama town, Lee wove together a tapestry of Southern life in the Depression, a world where racism was unknown because “everyone knew” that Blacks were inferior, that they should be separated from “good white society,” and that to feel sympathy for a Black person was unthinkable. And if everyone feels a certain way, then that’s just the way things are.

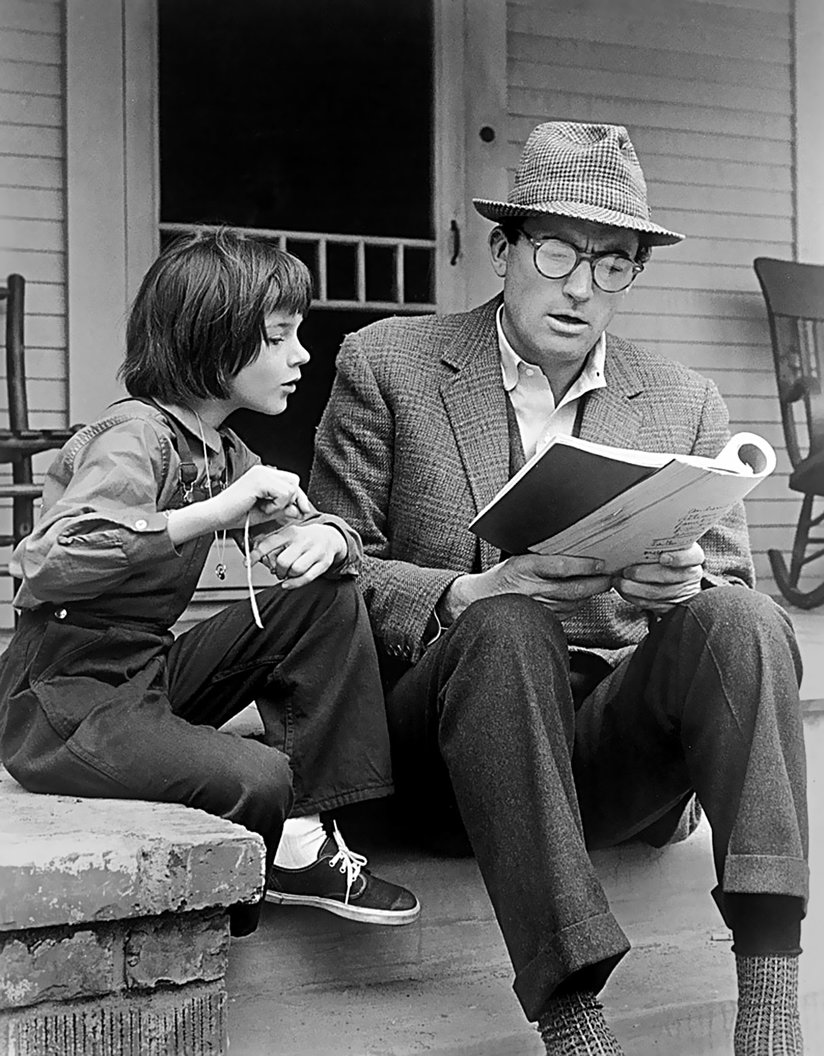

To Kill A Mockingbird focuses on small-town Southern lawyer Atticus Finch, who is appointed to defend a Black man accused of raping a white girl. Although it is plain that the defendant is innocent, the all-white jury finds him guilty.

Despite the fact that the novel deals head-on with such subjects as rape, bigotry and racial inequality, it is a tale told from a place of love with a generous dose of warmth and humor, and Atticus Finch, through his simple integrity and courage in the face of intractable prejudice, has become a moral compass for many.

Lee, a white Southern author writing about racism in her backyard, took hold of a subject by the scruff of the neck that, at the time, no other white Southern writer had ever touched before.

Despite the fact that the novel deals head-on with such subjects as rape, bigotry and racial inequality, it is a tale told from a place of love.

Masterpieces are masterpieces not because they are soaring works of art, but because they communicate a message that transcends the time and place in which they are set. They speak to the souls of each of us—who we think we are, and who we’d like to think we can be. A true masterpiece challenges us to look a little further and try a little harder.

To Kill A Mockingbird appeared on bookshelves in 1960 just before the Civil Rights movement exploded into the nation’s consciousness. Whether or not it contributed to the momentum of that movement is fodder for debate elsewhere, but that the book was influential in the extreme—possibly even on a level with its predecessor by a century, Uncle Tom’s Cabin—is beyond argument.

Civil rights activist Andrew Young confessed that, at first, he had no interest in reading the book, involved as he was with the real-life conflicts and injustices it mirrored. But after reading it, he reflected that Ms. Lee’s novel, “Gave us hope that justice could prevail.”

To Kill A Mockingbird’s pages offer us a look at the disenfranchised, the misunderstood, the outcasts of society. They shine a light on Tom Robinson, the Black man wrongly accused, and also on Boo Radley, the recluse who stays hidden in the shadows, the prey of local suspicion and rumor until the very end of the book where his courage and kind heart are revealed.

In a way no scholarly treatise or forensic statistical analysis ever could, the book opened the eyes of its audience, particularly its Southern readers, to their generations-long, casual acceptance of injustice and their indifference towards inequality. By seeing the events of the book through the eyes of a child, Atticus’ daughter, Scout, one experiences the story through the sensibilities and feelings of an innocent.

It is hard enough to get a person to look, to see things as they are, and to realize that a change is needed—harder still when you’re doing it through the pages of a book. Harper Lee coaxed us, through her endearing characters, through her wit and storytelling, and through the indisputable truths she etched in bold, unavoidable relief, to simply look, and so to change. The book, therefore, like other essentials of life, is not that easy for some to take.

Toward the end of the novel, a neighbor comments to Atticus’ son, “I simply want to tell you that there are some men in this world who were born to do our unpleasant jobs for us. Your father’s one of them.”

“There are some men in this world who were born to do our unpleasant jobs for us. Your father’s one of them.”

Harper Lee asks us to be our own Atticus, to face and fight wrongnesses when we see them, although it would be far easier to let someone else tend to that “unpleasant job.”

In 2012, the American Film Institute celebrated a century of filmmaking by conducting a nationwide survey to name the number one movie hero of all time. The public had many champions to choose from: superheroes, gunslingers, lawmen, soldiers and sports stars, among others. The people’s choice as the number one movie hero of all time was no musclebound superhero, nor a John Wayne, nor a Rocky. It was Atticus Finch.

Harper Lee, like her character, Boo Radley, with whom she identified, shunned the spotlight, giving her last interview in 1964. She also turned down many requests to write an introduction to the book, insisting that the book did a perfectly good job of speaking for itself. The closest Lee got to an interpretation of her own work was this: “Surely it is plain to the simplest intelligence that To Kill A Mockingbird spells out in words of seldom more than two syllables a code of honor and conduct...”

Harper Lee’s masterpiece is a reminder to each of us that there is a code of honor and conduct, native and eternal to us all. Possibly, several decades or centuries hence, in some enlightened, golden age, To Kill A Mockingbird will be viewed as a historical curiosity of a bygone era when mindless hate and injustice once flourished. We are still a fair distance away from that golden age, but if we are to get there, it will be achievements like Harper Lee’s novel that provide the guiding beacon to light our way.