One Century Later, What the Tulsa Massacre Can Tell Us About Today

Today marks the 100th anniversary of a tragic event in the United States’ long struggle to reconcile its commitment to human rights and personal freedom with its dark legacy of racism and bigotry.

As we confront a 10-year high in hate crimes, the 1921 destruction of a vibrant and prosperous Black neighborhood in Tulsa, Oklahoma by a white mob has important lessons for today.

Tulsa was a booming oil town, offering employment and thereby attracting people from throughout the country, including an energetic and enterprising Black population that built the Greenwood community within the city in the 1920s. Greenwood Avenue, the heart of the district, has been referred to as “the Black Wall Street,” with movie theaters, night clubs, luxury stores, its own library and the offices of many African-American doctors, dentists and attorneys.

He described unarmed citizens shot in the street, airplanes dropping fireballs on buildings and the general destruction of businesses, homes and lives.

On May 31, 1921, a young Black man was arrested after allegedly assaulting a white woman. The charges were later determined by the police to be unfounded and the man released a few days later, but not before a white lynch mob gathered outside the courthouse where he was being held, determined to mete out its own version of justice. The mob was stopped by law enforcement. Black citizens of the Greenwood neighborhood also showed up to defend the arrestee and a scuffle ensued between them and the white mob.

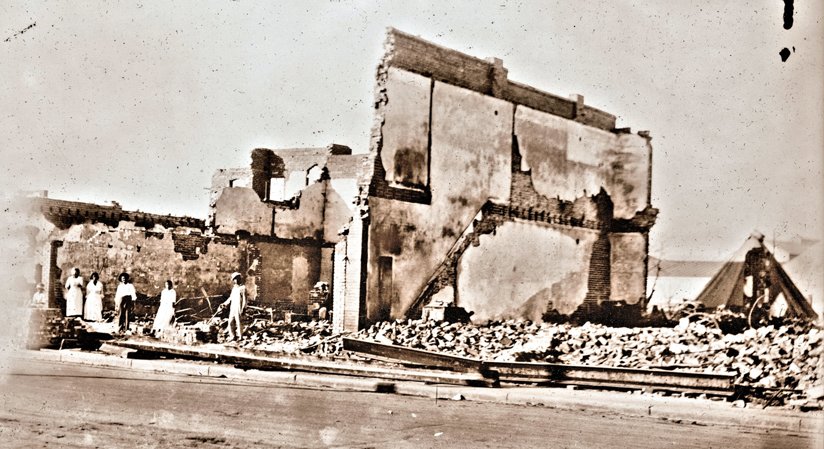

The situation escalated to a full-scale assault on Greenwood by members of the white population. Many houses and businesses were burned to the ground and white vigilantes raged through the district looting and shooting to kill. The Greenwood community was almost entirely destroyed. Thousands were left homeless.

The official death toll of 26 Blacks and 10 white people killed is believed by nearly all who have studied the tragedy to be an undercount with the death toll probably over a hundred.

A prominent Black lawyer wrote an eyewitness account several years later. He described unarmed citizens shot in the street, airplanes dropping fireballs on buildings and the general destruction of businesses, homes and lives, stating “for fully forty-eight hours, the fires raged and burned everything in its path and it left nothing but ashes and burned safes and trunks and the like where once stood beautiful homes and business houses” and also “the only hell was the hell on this earth, such as the Race was then passing through.”

None of those who participated in the killings and property destruction were ever convicted of any crime.

The National Guard was called to the scene but did not prevent the destruction. They did, however, detain thousands of Black citizens who were held under guard for several days under what was termed “protective custody.”

Many Greenwood residents spent a large part of the next year living in tents while they rebuilt their homes—which they did despite the denial of insurance coverage for the damage.

None of those who participated in the killings and property destruction were ever convicted of any crime.

Local politicians, clergy, the press and law enforcement placed the blame for the incident squarely on the shoulders of the Greenwood’s Black population. A grand jury called to investigate the tragedy included in its report: “We find that certain propaganda and more or less agitation had been going on among the colored population for some time. This agitation… was accumulative in the minds of the negro which led them as a people to believe in equal rights, social equality and their ability to demand the same.”

Or, as echoed by an editorial in a local newspaper addressed to Tulsa’s Black population: “Avoid the boastful intriguers who prate to you of race equality. There has never been such a thing in the history of the world. Nor will there ever be.”

Why would those responsible for restoring order and achieving justice blame the victims and, in particular, their desire for equal rights? Of course racism and the underlying lie that white people were superior to all others was part and parcel of the American experience at the time, and from that lie came the assumption that only white people were fully entitled to the freedoms and opportunities afforded by the law. Slavery had been abolished to be replaced by Jim Crow laws, in place in much of the United States at the time of the Tulsa massacre, which restricted where Blacks could live and conduct business as well as their participation in society generally.

Comparing society as it stood one hundred years ago to now, it is possible to see positive changes. Thankfully, in 2021, a grand jury, major media outlet or mainstream politician would never condemn a belief in social and racial equality as some kind of disordered mental state coming as a result of “agitation.”

Further, surrounding the 100th anniversary of this tragedy, there is a growing willingness to come to terms with the devastation and racism that made it possible, with the President of the United States visiting Tulsa along with other prominent persons. Still others are pushing for reparations for victims and their descendants and taking actions to acknowledge the tragedy and learn from it. All of this is a far cry from the years after 1921 when the destruction of Greenwood was mostly ignored by the media and government.

We need to understand that ill-intentioned falsehoods, when unchecked, lead to hatred and bigotry. And we must do everything in our power to prevent such falsehoods from spreading.

That is the plus side. But unfortunately, while the current response to Tulsa shows we have come a long way, bigotry is still alive and well today, as evidenced by the number of hate crimes occurring in the United States, detailed in the FBI’s annual report. Victims have been targeted not just because of their race or ethnicity, but also their religion, sexual orientation, gender or disability. When we look at how many people have been or could be the victims of a hate crime, it is clear that every member of society has a vested interest in preventing tragedies like the events of Tulsa from happening again, as well as changing the attitudes that made Tulsa possible. We need to understand that ill-intentioned falsehoods—like the notion that a desire for racial equality is what causes riots—when unchecked, lead to hatred and bigotry. And we must do everything in our power to prevent such falsehoods from spreading.

It is also important to realize that destruction caused by racism was not the whole story of Tulsa. There were many men and women who would not let Greenwood die, one of whom was Buck Franklin, the prominent lawyer whose description of the massacre is quoted above. Franklin helped in the defense of many of the Greenwood citizens in the massacre’s wake. He successfully battled the government of Tulsa in its efforts to rezone the land to prevent the construction of homes, and prevailed before the Oklahoma Supreme Court with the result that Greenwood was rebuilt within a few years. Like his fellow Greenwood residents, Franklin continued to do his job, for a while running his law practice from a tent. His manuscript of the events of that time was found only a few years ago. The wreckage of his community was not all there was to his story. He went on to describe its reconstruction and ended his piece thankful for “the wonderful, almost miraculous come-back of the Race here in the accumulation of property and in the acquiring of a larger, richer and fuller spiritual life.”

Since then, Greenwood has had to battle against many challenges, but the spirit of resiliency is still very much in evidence.

In addition to teaching us the dangers of living with lies, Tulsa can provide another example that there is no better answer to hate and suppression than to stand up to it and prevail in spite of it. In the years since Tulsa, many individuals and groups who were on the receiving end of bigotry, due to their race, religion or otherwise, have stood up and prevailed and continue to do so in ways which have and will enable us to live in a happier, better and more inclusive world.