-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

Why Black History IS History

“Won’t it be wonderful when black history and native American history and Jewish history and all of U.S. history is taught from one book. Just U.S. history.”

– Maya Angelou, poet, memoirist, and civil rights activist

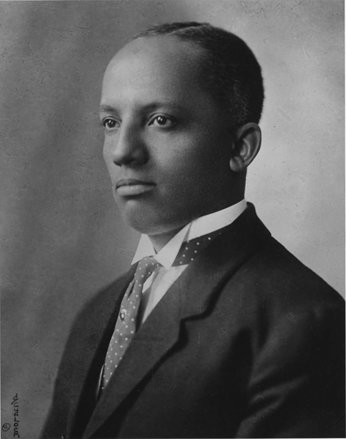

Carter Woodson who first conceived of Black History Month (originally “Negro History Week,” to be observed the second week in February to mark the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln) understood that Black History was so much more than a struggle for recognition and rights. It was a lush catalog of accomplishments that have enriched us to this day.

It was the preservation and crystallization of that Black History in the cultural and political memory of our nation that Mr. Woodson had in mind.

Woodson had little time to waste. He spent 18-hour days discovering, gathering, filing and disseminating a sometimes hidden, often forgotten, but always integral aspect of American history and American life. He regarded his mission to recover and restore to the nation’s consciousness the role of Blacks in its history. “If a race has no history,” he wrote, “it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated.”

His seminal work, The Mis-Education of the Negro, still stands after nearly 90 years in print as an eloquent plea not just for equal rights, but for equal education as well, making the point that for too long Blacks had been denied their say in an American history curriculum that was skewed toward white supremacy. In one chapter Woodson writes, “I don’t understand why they would devote all this time [in history class] to Europe, descendants of Europe, and not give equal time to the origins of Africans.”

Black History Month in the United States offers us a gallery of memorable dates to observe, all with a common theme: greater freedom for Blacks as the days of slavery recede in the nation’s rearview mirror.

In 1926 he unveiled what would be known as Negro History Week. Its purpose, he wrote, was “not so much a Negro History Week as it is a History Week. We should emphasize not Negro History, but the Negro in History.”

Carter Woodson’s concept in 1926 of a Negro History Week was expanded 50 years later to encompass the entire month of February.

One month—and the shortest one at that—is still far, far too little to explore, learn and reflect upon the extraordinary contributions of Blacks. Many of us know at least one or two of the dates:

- February 1: Passing of the 13th Amendment, outlawing slavery

- February 3: Ratification of the 15th Amendment guaranteeing the right to vote regardless of race

- February 4: Birthdate of civil rights hero Rosa Parks

- February 12: Founding of the NAACP

- February 14: Birthdate of Frederick Douglass (chosen by himself as his birthdate, as, born into slavery, no birthdates were noted—only purchase dates)

- February 18: First anti-slavery resolution, passed by the Quakers of Germantown, Pennsylvania in 1688

- February 23: Harold Washington wins the Democratic primary for mayor of Chicago. He would go on to win the election and become Chicago’s first Black mayor.

Black History Month in the United States offers us a gallery of memorable dates to observe, all with a common theme: greater freedom for Blacks as the days of slavery recede in the nation’s rearview mirror.

But Black History isn’t just about strides made for equal rights in America. Equal rights, after all, are something that everyone already has simply by the privilege and good fortune of being human. Equal rights, human rights, God-given rights—whatever you wish to call them—are not things to be “granted” by a legislative body nor by a signed document by a head of state, nor even by a majority vote of the populace. Equal rights shouldn’t have to be lobbied for, agitated for, or even fought for. All God’s children have always had equal, inalienable human rights and always will for eternity.

If we were to delve into the contributions of Black filmmakers, musicians, poets, artists, actors, novelists, singers; of military heroes, sports figures, entrepreneurs, cultural icons, economists, statespersons; of philanthropists, scholars, thinkers and religious leaders, to name just a very few of the categories where Blacks have excelled and shaped our lives—more often than not in the face of heart-wrenching odds—were we to attempt that, this would no longer be an article, it would be, well, Black History.

One day hence, possibly within the present lifetimes of some, there will no longer be a need for a specially designated time, for a “Black History Month”—for Black History will have been accorded its proper place in the chronicles of mankind as just that: History. Or as Carter Woodson himself said, “What we need is not a history of selected races or nations, but the history of the world void of national bias, race hate, and religious prejudice.”