-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

Why a Scientologist Wished She’d Gone to South Africa Sooner

I didn’t want to visit South Africa.

There, I said it.

But I am glad I did, and I wish I’d gone sooner.

My husband is from South Africa—Durban to be precise—born and raised. He left when he was 16 years old. We met when he was 18 in sunny Florida, in the USA where things are much more “normal”…and “civilized.” Mostly.

You have to understand my aversion to South Africa in proper context though:

When my husband and I were getting acquainted with each other in early 1989, we shared with each other the details of our upbringing, and I got my first glimpse of this complicated part of the world.

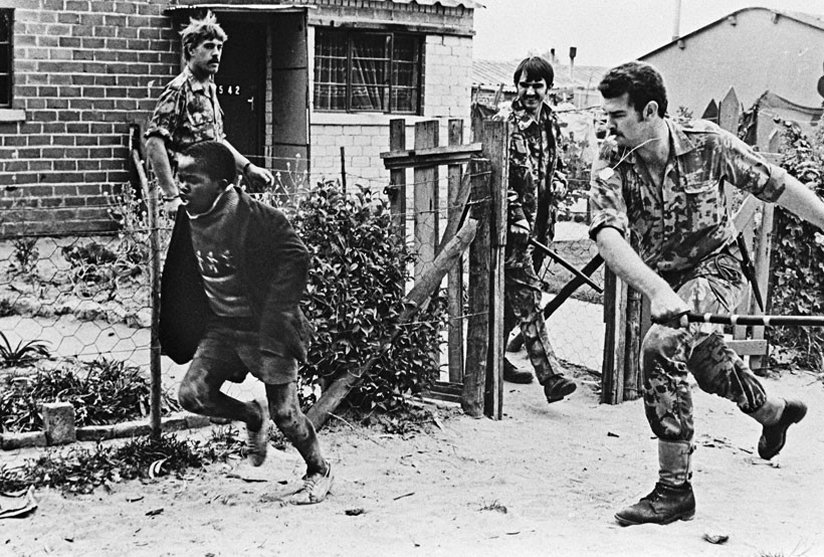

He told me that in his country, they had this thing called “apartheid.” I was stunned and horrified as he explained that he had been raised in a place where people were treated differently because of the color of their skin. I actually thought he was kidding. Because, from my happy little bubble of melting-pot goodness, this was unthinkable. Separate washrooms, buses, beaches, shops, schools and even towns, based on race?? Just no!

I was relieved to find that he didn’t like it either, despite having been raised with it his entire life. And though he still had family back home, I could not bring myself to go to a place where people were treated differently based on the color of their skin.

As our family grew, my reticence also grew. How could I rationalize this to my children? I couldn’t. And they would have the dilemma of being surrounded by adults who supported that system and so didn’t deserve the respect or courtesy that should be granted by children. So, I chose not to visit at all.

We made excuses that were valid: the cost for so many international tickets, the long flights, etc.

Then apartheid fell, and there was freedom and equality, and confusion and chaos as South Africa struggled to find her feet and her place. And I heard stories of horrific crimes—mostly black against black, but definitely against white as well.

You know how most people have a friend who has a friend who knows someone who got mugged? Well, for us, we knew many people who had been mugged, carjacked, robbed, shot and/or violated in some way in South Africa. Johannesburg had even earned the title of the “Murder Capital of the World.” These were the bits and pieces I’d heard for years after. It saddened me, and, again, I could not bring myself to visit.

When family or friends from there came to visit us, I noted that they were anxious when we went out after dark. If we stopped at a traffic light in a quiet area at night, they almost panicked as they explained that you just would not stop at a light (they call them robots) at night in Johannesburg for fear of being carjacked or robbed.

I just could not fathom living like that.

Time passed, and we continued to hear stories from afar. Stories of the wonder and beauty, and the dark and turbulence as South Africa took on a different shape. To me, the problem seemed vast and complicated. How could I possibly visit a nation that was still so broken, and what could I do to help her heal and become the beautiful wonder that she could be?

Then, this past November, we had an opportunity to go to South Africa for just a few days to help some friends.

All I can say is that I wish I hadn’t stayed away so long.

I didn’t want to go. Honestly, it frightened me. But I plucked up my courage, and I went anyway.

We stayed for less than a week in Johannesburg, and then went back home, only to return again in December for 10 days to Johannesburg and Durban.

All I can say is that I wish I hadn’t stayed away so long.

My husband and I explored his old neighborhood, his high school and other places of his childhood. We found a great melting pot of people of many colors, and so many families out and about. There were mixed couples and families, and people of various faiths, and many people of goodwill. I didn’t find myself surrounded by racists—black or white. Just lots of people.

Wow. And it was then that I realized that I’d fallen victim to discrimination.

I was quite nervous at first, suspicious of everyone who looked at me, worried that at any moment I might be a victim of some crime. At one point, we were driving down a main road with some local friends and the sun was fading. He slowed to a stop at the red traffic light, and I asked him anxiously, “Why are you stopping? Shouldn't you keep driving? Isn’t it dangerous to stop at the lights?” I was actually alarmed. After all, I’d heard the stories. But he just laughed and said, “No. And it’s illegal to run the light.”

Wow. And it was then that I realized that I’d fallen victim to discrimination. Me, a self-pronounced champion of human rights had bought into the idea that this place and its people were bad. And it just wasn’t true.

Generally speaking, many parts of South Africa might be similar to some inner cities in the U.S. There is a heightened level of security that is necessary, but it’s not the whole country and its people that are worrisome. Like most places, it’s a small percent that cause the trouble. In fact, most of the population wants to work, raise a family, have a home, and feel secure. The malls are bigger than the ones we have in the U.S., and there were plenty of people shopping for the holidays. They were friendly and helpful, and smiled when I smiled.

Southern Africa is beautiful and perhaps untamed, and quite spiritual, and very worthy of help and real solutions. Like any community, it needs support and assistance. Sure, there are drug problems, morality issues, illiteracy and crime, just as there are in many other places.

This is what I see for South Africa, and I know that her people see it too.

At one point, Colombia was a place that the U.S. Tourism Department discouraged Americans from visiting because of the crime rate. But after an extensive campaign of disseminating the book, The Way to Happiness, the country’s crime rate plummeted and communities united, creating a calm and beautiful Colombia that is now a top recommended tourist destination.

This is what I see for South Africa, and I know that her people see it too.

Like these words from the late Nelson Mandela: “We can change the world and make it a better place. It is in your hands to make a difference.”

When the brand-new Church of Scientology of Johannesburg North opened in December 2017, there were a couple thousand people in attendance including tribal leaders and at least one king I saw personally. There were pastors and holy men and women of distinction, and they were all there with a common purpose and belief that, together, they could make a better world because they all faced the same challenges in their own communities.

Like these words from the late Nelson Mandela: “We can change the world and make it a better place. It is in your hands to make a difference.”

I will be back again and again to do what I can to help make that difference, and it is my sincere wish that many others will too.