-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

What Does it Take to Maintain Freedom of Religion Against Hatred and Intolerance?

When my father’s family came to the United States from Sweden in the 1800s, they stayed in touch with relatives who remained in what they called “the old country,” and when I took a summer to hitchhike around Scandinavia in 1973, I wanted to meet them, especially Gunnar Alfred Sjöholm. Gunnar had been a Lutheran minister in China until the Communist Revolution. He had escaped to Taiwan in about 1950 and then took a position in Finland, finally returning to Lund, Sweden.

I was a bit intimidated at first. I left university without graduating, loved sports and wrestling and knew very little about politics or the problems of the world. Gunnar studied English at Oxford and Cambridge, Chinese at Berkeley, German in Berlin, studied Chinese philosophy and would eventually receive a PhD at age 76. Gunnar was also a “Prosten”—an official in the Swedish state church—and in 1954 was a translator with the Swedish delegation to the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission in Panmunjom, Korea. His wife Lois was Norwegian, but they met and married in China and she spoke English with a Chinese accent.

I was 28 when I met Gunnar and Lois and their son Anders. When they asked me what I thought about Nixon and Watergate, I had to buy an English-language news magazine to find out what they were talking about. They knew more about my country than I did, and Gunnar told me how fortunate I was to live in a democracy with freedom of speech and religion. (I took those things for granted—he didn’t.)

Gunnar took me walking in Lund, showing me the city and educating me about Skåne, the southernmost region in Sweden where Lund is located. Gunnar was interested in everything and had an encyclopedic knowledge of the region. As we walked through Lund University’s clouds of bicyclists, Gunnar told me about the buildings, history and culture. He told me what street names meant in English, and how the glaciers in the north scraped off the topsoil down to bare rock, while Skåne escaped the glaciers and thus could sustain agriculture. I wondered how much I could tell him about my own region, Oregon’s Willamette Valley. Certainly nothing as comprehensive as what he was telling me.

The man—whether he knew it or not—was following a very old tradition, said Gunnar. A jester made one look, inspect and reevaluate the things one valued most.

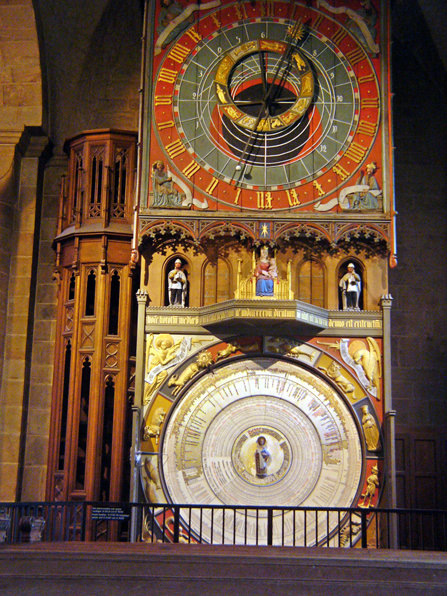

We walked to Lund Cathedral. Built in the 11th century during turbulent times, it had a cistern in the basement in case of siege, arrow slits and heavy stone walls. Inside it was as if one entered the darkness of the 11th century all over again. An astrological clock built in the Middle Ages still ran on wooden gears.

Suddenly, as we talked in the church office, a man rushed in, and began shouting and dancing around. I didn’t understand what he was saying and it looked like he was either crazy or trying to cause trouble. I was embarrassed for Gunnar, as he was showing me a place he treasured and this man was spoiling it. My first impulse was to push the guy outside.

But that was not the way of my Swedish host. He said Sweden valued freedom of speech and religion, and stood calmly watching the man and interpreting for me what he was saying. The man was insulting the church, church officials, even God himself. I was surprised at how calm Gunnar was. After the man ran out, Gunnar told me that making fun of established institutions was the job of the fool or court jester in the Middle Ages. The jester—unlike any other subject of the king—had freedom of speech specifically granted by the king. So the jester could joke about the church, government officials, even the royal family without fear of punishment.

The man—whether he knew it or not—was following a very old tradition, said Gunnar. A jester made one look, inspect and reevaluate the things one valued most. Gunnar’s ability to put such an act in historical context, to understand it as more than hate and to not condemn or lash out was something I found inspiring but a bit mysterious. How could one rise above the kind of anger and resentment that I felt toward the “jester?”

Several years later, I became a Scientologist, and found that a few mean-spirited people seemed to delight in attacking my Church, spreading lies in newspapers and later on the Internet. I remembered the incident at Lund Cathedral and Gunnar’s reaction to it.

And then in “What is Greatness?” by Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard, I discovered something profound that, for me, put the pieces into place. “To do one’s task without becoming furious at others who seek to prevent one is a mark of greatness—and sanity.”

I see that kind of greatness in many people who follow a spiritual path. The Jehovah’s Witness knocking on my door, Muslim women distributing information at the California State Fair, Christians feeding the homeless, Scientologists passing out anti-drug booklets, Mormon teens on their two-year missions, and all those offering help in the midst of what can be a cynical and materialistic culture.

We can be granted freedom of speech and freedom of religion by the Constitution or the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, but to be effective, those rights must be understood and applied by individuals with certainty and resolve. Only then can we rise above narrow-mindedness, hatred and intolerance.