-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

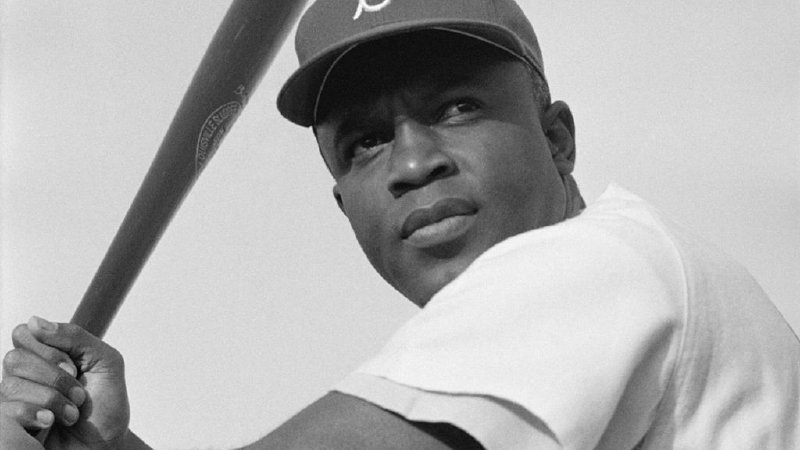

Civil Rights Icon Hank Aaron: A Tough Out, On and Off the Field

“Here’s the pitch by Downing. Swinging. Here’s a drive into left center field! That ball is gonna be… outta here! It’s gone! It’s 715! There’s a new home run champion of all time, and it’s Henry Aaron! The fireworks are going! Henry Aaron is coming around third! His teammates are at home plate. And listen to this crowd!”

– Atlanta Braves sportscaster Milo Hamilton, calling Aaron’s record-breaking home run, April 8, 1974 in Atlanta, Georgia before a sellout crowd

Hank Aaron was a tough out. This fact, as indisputable as the sun will rise in the east tomorrow morning, has been attested to by the unfortunate pitchers, great and not great, tasked with facing him over his 23 seasons in the major leagues.

But Aaron, who died at age 86 last month, leaves behind not just a legacy of athletic greatness but one of grace, bearing up against a continuous barrage of hate that only increased as the years passed and particularly as he began catching up to Babe Ruth’s hallowed record of 714 lifetime home runs.

(Photo from The George F. Landegger Collection of Alabama Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith's America, Library of Congress)

In 1973 and 1974, Aaron received more mail than any other individual nonpolitician in the United States—over 930,000 letters, much of it hate mail and death threats to him and his family should he break Ruth’s record.

As he described that period 20 years later in an interview with the New York Times: “It really made me see for the first time a clear picture of what this country is about. My kids had to live like they were in prison because of kidnap threats, and I had to live like a pig in a slaughter camp. I had to duck. I had to go out the back door of the ballparks. I had to have a police escort with me all the time. I was getting threatening letters every single day. All of these things have put a bad taste in my mouth, and it won’t go away. They carved a piece of my heart away.”

Though perhaps not as inspiring a speaker as a Jackie Robinson, nor as charismatic in leadership as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Hank Aaron is yet remembered as a civil rights icon in his own right because he played his game his own way—time and again displaying irrefutable evidence on the field that the color of one’s skin has nothing to do with one’s worthiness to compete. Later, as a baseball executive, he provided portals and opportunities to young people who, like him, had the cards stacked against them from the beginning due to nothing more than a circumstance of genetics.

Hank Aaron leaves behind not just a legacy of athletic greatness but one of grace, bearing up against a continuous barrage of hate.

As but one example of playing the game his way, most hitters study up on the pitcher they’re facing, sizing up how to react to the kind of pitch—curve, slider, fastball, off-speed—that pitcher is likely to throw.

Not Aaron. As Hall of Fame pitcher Fergie Jenkins observed, “Hank was diligent, very patient at the plate. He was swinging at his own pitch, not the one you were trying to get him out with.”

Aaron played the game of life the same way. Though he knew that to some he was an intruder, a usurper, an enemy to be beaten down just for the fact of existing, he nevertheless approached the course of his life patiently, diligently waiting for—and then pursuing—his own way, his own pitch from the very beginning. Enduring poverty as a child in Mobile, Alabama with no hope of obtaining the baseball equipment he needed, he improvised with whatever he could find in the streets of his neighborhood, practicing with sticks for bats and bottle caps for balls, playing in pick-up games on local sandlots, keeping his dream alive until at last landing his first professional job with the Prichard Athletics, an independent Negro League team, at $2 a game.

The last major league player who had done service in the old Jim Crow era Negro Leagues, Aaron recalled waiting out one rain-shortened game in a restaurant in Washington, D.C. during his stint with the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro American League. He would forever after be haunted by the sound of dishes being smashed in the kitchen, knowing it had something to do with him: “We had breakfast while we were waiting for the rain to stop, and I can still envision sitting with the Clowns in a restaurant behind Griffith Stadium and hearing them break all the plates in the kitchen after we finished eating. What a horrible sound. Even as a kid, the irony of it hit me: here we were in the capital in the land of freedom and equality, and they had to destroy the plates that had touched the forks that had been in the mouths of black men. If dogs had eaten off those plates, they’d have washed them.”

Once his playing days were over, Hank Aaron sought to widen the highway that he and the likes of Jackie Robinson and Willie Mays had forged, by taking on an executive position with the Braves. Baseball Commissioner Bud Selig tasked Aaron with forming programs through Major League Baseball that encouraged and facilitated minorities to take part in the sport.

Hank Aaron played the game the right way—his way. He never bent to fear, never chose the easy route, and never gave in just to protect himself or be agreeable. Instead, he faced what he needed to face and overcame what he needed to overcome to live the life he knew he could.

His legacy is a lesson to all of us when faced with the bitter fruit of discrimination, hate and intolerance: Be your own “tough out.”