-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

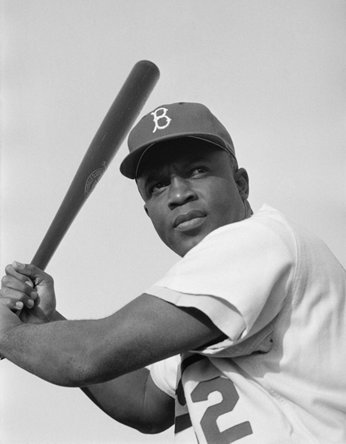

After 75 Years, Jackie Robinson Still Shows Us We Can Do Better, In Spite of Ourselves

All my life I had believed in payback. Retaliation. The most luxurious possession, the richest treasure anybody has is his personal dignity. I had a question. And it was the age-old one about whether or not to sell your birthright. Could I turn the other cheek? I didn’t know how I would do it, yet I knew that I must.

— Jackie Robinson

Jackie Robinson had a temper.

During his teen years, it landed him in jail twice for daring to stand up to abuse from a white person. Then in his 20s, he was court-martialed for refusing to go to the back of a military bus and for telling the bus driver to f—k off. Now he was being told to turn the other cheek, to restrain that temper for the sake of the bigger picture.

Jackie Robinson was the trial balloon, the test before the world that would show whether or not a Black man could successfully shatter baseball’s color barrier. Any false step, any loss of poise—a trivial matter in a white player—would have enormous consequences, not just for Robinson, not just for the future of baseball, but for the future of his race and any other minority people trying to get a seat at the table.

On October 23, 1945, Jackie Robinson gazed at what lay before him on the desk of the president of the Brooklyn Dodgers baseball organization. It was a contract. Before handing him the pen, Dodger president Branch Rickey told Robinson he must have the courage not to react to the epithets and obscenities he was about to face.

Robinson wasn’t sure he could do it. It was against his nature. He was accustomed to walking tall, of being proud of his race, even wearing white shirts which accentuated his blackness. He did not suffer bigots gladly. On the road in the Negro Leagues, if a gas station owner refused to let the team use the restroom, Robinson would say, “If you won’t let us use your restroom, we’re not buying your gas, and that’s a lot of gas for a team bus.” The owner would inevitably give in.

As Black baseball great CC Sabathia tells it, “This game is hard to play. Go out and play with the whole country watching you and with the pressure of all those African Americans on your back; because if he failed it’s maybe another 10 years before we get another Black player in Major League Baseball.”

Jackie Robinson could have played it safe, could have continued turning the other cheek, could have ridden out his career beloved, and faded into the sunset, the untarnished hero. But he chose not to.

After a season playing for the Dodgers minor league affiliate in Montreal, Robinson was promoted to the parent club Dodgers. On April 15, 1947—75 years ago this week—a Black man stepped onto a major league baseball diamond and into history. The experiment did not go well at first. During the month of April, with death threats appearing regularly in his mail, abuse raining down on him from the stands—with opposing teams threatening not to take the field against his team if he were to show up—Robinson did not do well. His batting average, hits, and other key stats were among the lowest in the league.

Rickey, under pressure to let Robinson go, instead traded the team’s other first baseman, leaving Robinson in sole possession of that position, an unprecedented show of confidence in the struggling rookie, who now wore special padding in his cap as a layer of protection against the fastballs thrown at his head.

Robinson responded to that show of confidence. His averages and stats skyrocketed, and he led the Dodgers to a pennant, garnering Rookie-of-the-Year honors, the admiration of millions and, most importantly, an open door making possible the Major League careers of, among others, Willie Mays, Roy Campanella, Ernie Banks, Hank Aaron and Frank Robinson—all of whom earned baseball’s highest honor, Most Valuable Player.

(Photo from The George F. Landegger Collection of Alabama Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith's America, Library of Congress)

A Hall of Fame career ensued, but a look at the trophy room in Jackie Robinson’s house reveals where his priorities truly lay. One glass case against one wall contains his baseball honors, awards, pennants, and a championship. The remaining three walls are replete with certificates of appreciation, plaques, and proclamations for his achievements in civil rights.

Robinson wrote, “If I had a room jammed with trophies and a child of mine came into that room and asked what I had done in defense of Black people and decent whites fighting for freedom, and if I had to tell that child I had kept quiet, that I had been timid, I would have to mark myself a total failure in the whole business of living.”

“Heroes are needed by the people for reasons far beyond the game. And so, heroes have the people on their shoulders.”

Jackie Robinson could have played it safe, could have continued turning the other cheek, could have ridden out his career beloved, and faded into the sunset, the untarnished hero. But he chose not to. Once established as a force to be reckoned with in baseball, he pulled no punches, spoke his mind both on and off the field, and after his retirement from baseball used his celebrity and his words to continue fighting for equal opportunity and civil rights for all.

Twenty-five years after he broke baseball’s color barrier, Major League Baseball honored Robinson on the field before Game 2 of the 1972 World Series. The ceremony included a tribute from President Richard M. Nixon. Again instead of taking the easy route and being appropriately humbled by the occasion, Robinson, now suffering from diabetes and blind in one eye, said, “I am extremely proud and pleased to be here this afternoon, but must admit I am going to be tremendously more pleased and more proud when I look at that third base coaching line one day and see a Black face managing in baseball.” He died just nine days later at the age of 53.

It would be another two years before Major League Baseball would comply with Robinson’s dying wish.

Born a sharecropper’s son, and the grandson of slaves in a year when 21 Blacks were lynched in the state of Georgia alone, Jackie Robinson could not have known that in his short lifetime he would alter world history and affect the lives of many millions of people.

Eulogizing Robinson, the Reverend Jesse Jackson said, “Champions win events, they hit the big home run… and people hoist them on their shoulders. But Jackie was a hero. Heroes are needed by the people for reasons far beyond the game. And so, heroes have the people on their shoulders.”

This week, as all big-league ballplayers wear Robinson’s number, 42, in honor of the 75th anniversary of the first Black man to set foot, as an equal, on a major league ball field, we remember that for the greater part of his life, Jackie Robinson carried America on his shoulders and made us all better for it.