-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

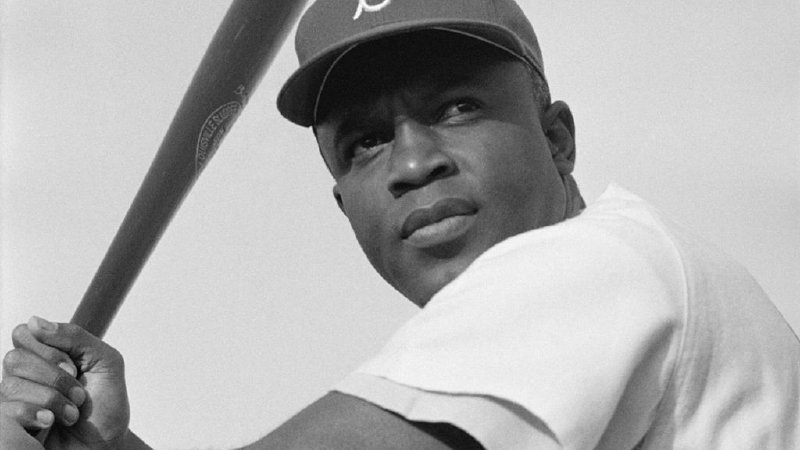

Sidney Poitier Risked His Life for Equality and Human Rights

It was a scene out of a movie. A car streaking along a dark country road at night, a second car at its rear, intent on stopping it and murdering its occupants. Gaining on its quarry, the car in pursuit erupts with gunfire, the target car desperately weaving to elude the bullets, its driver searching for some way to throw the attackers off its scent.

Only this was no movie. The scene was real. Sidney Poitier and his friend Harry Belafonte had arrived in Jackson, Mississippi that night in 1964 to deliver $70,000 to the financially-strapped Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Student activists in Mississippi had embarked on a two-month “Freedom Summer,” a test of multi-racial democracy, featuring over 700 white volunteers who, together with Blacks in the state, would put together arts programs, classes in civics and literacy, and training in voter registration among other projects. But without funding, it was doomed before it began.

Fresh from his groundbreaking Academy Award for Best Actor, the first such ever awarded to a Black man, Sidney Poitier, who passed away last week, had no reason to take risks. A blossoming career as a leading man in motion pictures beckoned. Already hailed as the “Hollywood Jackie Robinson,” it would have been understandable had he balked at Belafonte’s invitation to accompany him to race-torn Mississippi on a dangerous mission. But Poitier, seeing a cause bigger than himself, agreed to go.

Armed vigilantes discovered the plan to finance Freedom Summer and set out to kill the two before they arrived at their destination. Fortunately, the actors eluded their would-be killers and delivered the funds safely. Freedom Summer, against all odds, and despite browbeating, scare tactics, and murder, raised awareness internationally of the struggle for civil rights in America. Forty Freedom Schools serving over 3,000 students ultimately grew from the movement.

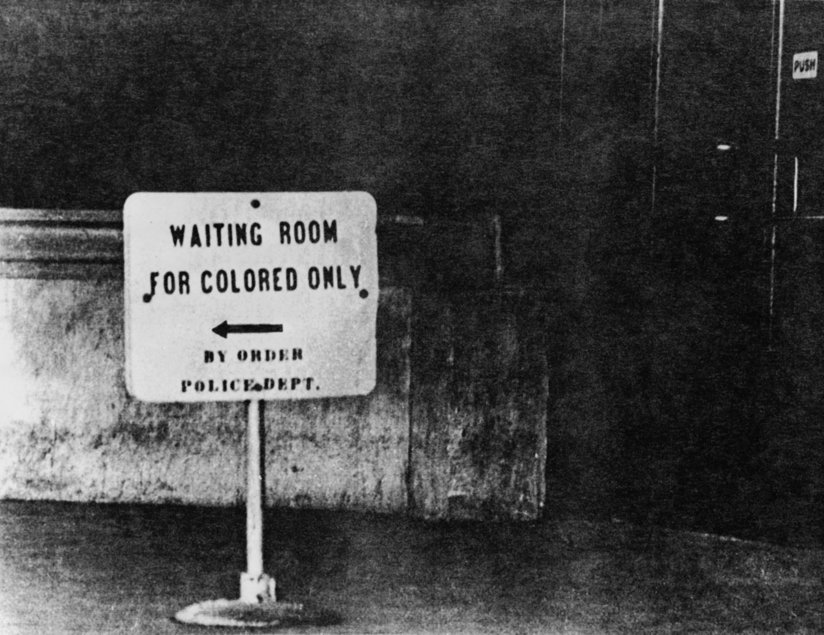

That year, the national attention Freedom Summer had amassed for the civil rights movement persuaded President Lyndon Johnson and Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964, ending segregation in public places and making it a crime to discriminate in hiring on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin. The Civil Rights Act was followed the next year by the Voting Rights Act, which put an end to poll taxes and literacy tests as well as the violence and intimidation that had kept Blacks from exercising their constitutional right to vote.

Had Poitier and Belafonte not made it to their destination, had the gunmen had their way, had the volunteers not been funded, had there been no Freedom Summer and no national attention focused on civil rights, would bigotry and hate, along with their offspring—exclusion, abuse, and bloodshed—have continued to flourish unabated?

Thanks largely to this forgotten episode in Sidney Poitier’s life, we don’t need to ask that question.