-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

The Rabbi and the Bigot—A Story of Redemption

American researcher and Scientology Founder, L. Ron Hubbard, published an essay in 1965 wherein he posits the importance of using and teaching the “correct technology.” Simply put, there’s a right way to do things and a wrong way to do things. The right way to turn on a light switch is to flick it to the “on” position. The wrong way is anything else: yelling at the light switch, shooting the light switch with an assault rifle, reasoning with the light switch, posting guards and checkpoints around the light switch, throwing away millions of taxpayer dollars for a government study on why the light switch won’t turn on, and on and on.

How do we know if we’re using the correct technology on anything? Simple. It works.

One Sunday morning in 1991, Rabbi Michael Weisser of the South Street Temple in Lincoln, Nebraska, answered his phone to hear a voice: “Hey, Jew Boy, we’ll make you sorry you moved here.”

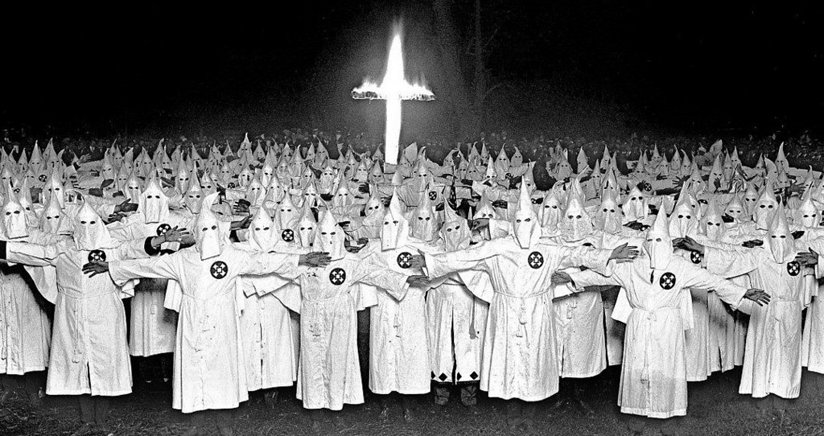

A few days later, the Rabbi found a package on his front walk containing anti-Semitic, pro-Nazi pamphlets and a card reading: “The KKK is watching you, scum.”

The police tracked the message and pamphlets to Larry Trapp, the state Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan, who kept a full stock of loaded artillery and pro-Hitler propaganda in his apartment. They advised the Rabbi to move his family out of town.

Once a week Rabbi Weisser would leave a message of love and encouragement on Trapp’s voicemail.

Rabbi Weisser elected not to. Instead he found Trapp in the phonebook, phoned him, waited through the venomous, hate-filled outgoing message, and then left one of his own: “Larry, there’s a lot of love out there. You’re not getting any of it. Don’t you want some?”

Once a week, Rabbi Weisser would leave a message of love and encouragement on Trapp’s voicemail. When he learned that Trapp was nearly blind and wheelchair-bound due to diabetes, he left this message: “Larry, why do you love the Nazis so much? They’d have killed you first because you’re disabled.”

After several weeks of leaving messages, Rabbi Weisser dialed Trapp, and instead of the usual vitriol, heard instead a click and a hoarse voice: “What do you want?!”

The Rabbi answered, “I thought you might need a ride to the grocery store.”

After a long pause, the voice mumbled, “Quit bothering me.”

A few nights later Rabbi Weisser’s phone rang. He could tell from caller ID it was Trapp.

“Hi, Larry, how are you?”

After a moment Trapp said timidly, “I want to get out of what I’m doing and I don’t know how.”

The Rabbi and his wife drove out to Trapp’s apartment, moved him into their house, introduced him to their friends, cared for him, ran errands for him, and let him do some office work at the temple. He had never wanted to hate people. His father, a towering bully, had taught him by example and constant beatings. He eventually renounced the Klan, apologized to the congregation and converted to Judaism. When he died from his disabilities, his Jewish funeral was attended by scores of his new friends.

Hate is an incorrect technology. It simply doesn’t work. People do have a vast potential to hate, which can be tapped. We’ve all seen that. But people also have a vast potential to love, which likewise can be tapped. We’ve seen that, too.

Rabbi Weisser used the correct technology to convert a hater into a decent human being. He could have run away and left the hater to hate. Instead he chose to fight hate with love.

Was he scared? Sure. The police thought he was crazy—that he was risking his life and the security of his family. But sometimes it takes courage to apply the correct technology when everyone and everything, including your own gut, tells you not to.