-

HOME

-

WHAT IS STANDOur Mission Our Values Our Help Contact

-

WHAT WE FIGHT FORReligious Freedom Religious Literacy Equality & Human Rights Inclusion & Respect Free Speech Responsible Journalism Corporate Accountability

-

RESOURCESExpert Studies Landmark Decisions White Papers FAQs David Miscavige Religious Freedom Resource Center Freedom of Religion & Human Rights Topic Index Priest-Penitent Privilege Islamophobia

-

HATE MONITORBiased Media Propagandists Hatemongers False Experts Hate Monitor Blog

-

NEWSROOMNews Media Watch Videos Blog

-

TAKE ACTIONCombat Hate & Discrimination Champion Freedom of Religion Demand Accountability

Race, Religion & Bridges to Understanding

A group of almost 600 people, mostly African-Americans, gather on a road leading east out of a small southern town. They begin to walk. Their destination is the state capital, 54 miles away.

They have only come six blocks when they arrive at the bridge that marks the edge of town. They cross this bridge. Waiting for them on the other side is a line of white State Troopers, some on horseback. The group is told to turn back and go home. A minister speaks to the officer in charge, but the officer says there is nothing to discuss.

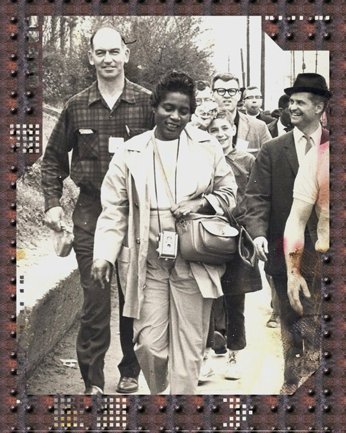

The walkers do not immediately disperse and the troopers begin attacking on horseback and on foot, beating them back with clubs and tear gas. A female leader lies unconscious on the road near the bridge and a photo is taken. That photograph appears in newspapers and magazines around the world. Millions of people learn of a town they have never heard of before: Selma, Alabama.

The purpose of the walk is to bring attention to the fact that African-Americans are being denied the right to vote. In Selma’s county, where 15,000 blacks are old enough to vote, only 130 are registered. By attacking the group, the troopers have unwittingly assisted in publicizing their cause.

That civil rights struggle grew, in large part, from religious strength and unity.

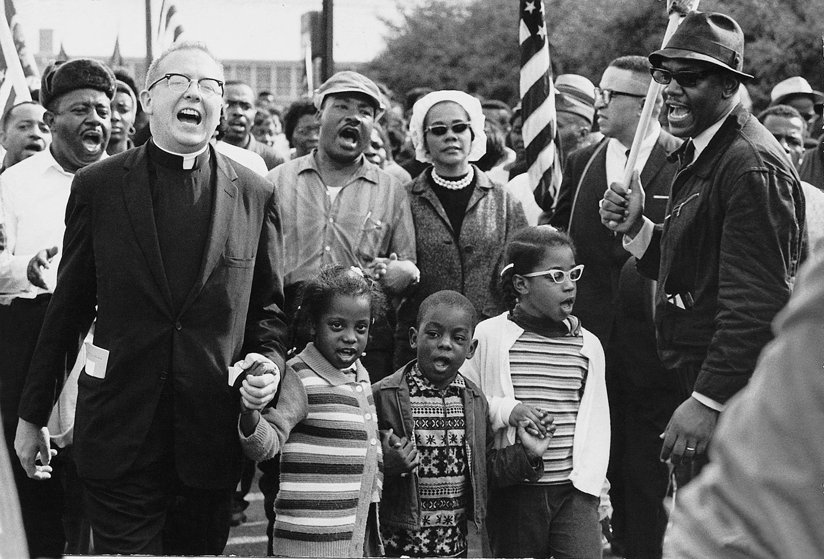

Two days later, on March 9, 1965, a group of 2,500 marchers coming from different parts of the country—one third of them white—gather in the same town. The group has strong ties to religion which has bound them together and provided them solace during these tough times. Many of the leaders are ministers. Among them is thirty-six-year-old Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Religious influences are particularly strong in this charismatic and inspiring orator. His very name is drawn from the great reformer Martin Luther who led a powerful religious protest 400 years ago.

This group walks up to and onto the same bridge. The troopers are there again, but they have been ordered to stand down. The marchers have also been issued a judicial injunction not to continue the walk, so after a few moments of prayer on the bridge, they turn back. However, that evening in Selma, a white Unitarian minister from Boston who arrived to join the marchers is beaten to death by members of the Ku Klux Klan.

For a third time, on March 21st, a group gathers to march. It consists of 8,000 people from all walks of life with spiritual leaders of multiple religions, races, and creeds. They approach the bridge and cross it. This time they are protected by troops ordered by no less than the President of the United States. Now they will go all the way to the capital of the state; Montgomery, Alabama.

A few days later, in the morning of March 25, a privately chartered plane flying at 5,000 feet approaches the Montgomery airport. In the plane are 26 passengers, including a young white boy, his father, and three other white men from a small Illinois town located across the Mississippi River from St. Louis, Missouri. All the passengers boarded the plane at sunrise in St. Louis with the purpose to join the march.

The boy, thrilled to be flying for the first time, often looks out the window at the blue sky above and billowing clouds below never having seen such a sight, but he still manages to pay attention to instruction being given by the group leader. He tells them that they are not wanted by the whites in Montgomery and they all could easily be arrested. They are looked upon as outsiders. They are all given a patch to wear showing they are outsiders and they should not pretend to be anything else. A few hours later, the plane lands in Montgomery and the group takes a decrepit bus to the outskirts of the city.

From this experience and many others, the boy is imbued with a sense of decency and belief in equal rights for all people.

The number of marchers has swollen to 25,000 as people have arrived from everywhere by all means of travel in the last few days. As they walk through the streets approaching the Montgomery capitol building, they are both cursed and applauded by inhabitants lining the streets.

The group from St. Louis tops a rise and sees before them a multitude of people crowding up to the capitol building a half-mile ahead. The day has been overcast but not cold. A light drizzle begins and umbrellas pop up like sprouting mushrooms. Then silence reigns as Dr. King begins to speak in the early afternoon.

The boy and his group cannot easily make out the words at this distance, but it is a speech imploring all men to overcome prejudice, to work in unity and understanding so that all can live in peace with freedom from violence and discrimination.

As the speaking concludes, the crowd begins to disperse, each individual seeking his own way home. The small group from Illinois sticks together. They manage to catch a ride from two African-American women and make it safely to the Montgomery airport where they charter a plane home. It helped that the boy’s father had invited along a six- foot-seven giant of a man easily weighing over 300 pounds and the largest man from their small town (though truth be told he is one of the gentlest souls one is ever likely to meet). Not all marchers are so fortunate. A white female is shot and killed by the Ku Klux Klan while transporting others to the same airport.

From this experience and many others, the boy is imbued with a sense of decency and belief in equal rights for all people—rights to enjoy the liberties so valiantly fought for, then guaranteed in the U.S. Constitution.

He also has strong spiritual beliefs like so many of the marchers. He grows up, graduates college, and joins a religion that matches and strengthens his beliefs. Though new in the 20th century, this religion has roots deep in the ancient East. It is the religion of Scientology. And, if not already obvious, the boy grows up to be me.

That civil rights struggle grew, in large part, from religious strength and unity. While their challenge is one of race, civil rights also include the right of an individual to practice freely the religion of his choice. And like the struggles of race—as old as mankind itself—religion has suffered a similar fate throughout the world since it first brought people together to express their spiritual nature and awareness of God.

Crossing the bridge in Selma symbolizes the need we all have to build bridges between ourselves and others. Through mutual respect and tolerance, we can build and cross those bridges and find the humanity in us all.